An Unexpected Murder Ballad

There's a chance that the song you're hearing on the radio isn't saying what you think it is. Today, we dig into pop music's oddest contradictions.

Five popular songs with unexpected meanings

- Semisonic's "Closing Time," which a friend of mine slags me about because I once argued on Twitter that it was "the best song of the '90s," is not really about a man trying to win over a lady at the end of the night. Instead, it's about the birth of Dan Wilson's first child. "It wasn’t exactly conscious, but it became pretty obvious as I was writing the song," the Grammy-winning lyricist told American Songwriter in 2010.

- "Drops of Jupiter," by Train, is also not really about a guy trying to win over a lady. It actually has a more somber meaning that makes the song's success heartwarming: "I feel asleep briefly—it felt like five seconds—and woke up with the lyric 'she's back in the atmosphere,' and wrote a song about it because I had recently lost my mother, and I'd dreamed she'd gone through this incredible journey and came back to tell me about it. But as I was writing it, it became a love story,'" singer Pat Monihan told Songwriter Universe.

- D'Angelo's "Untitled (How Does it Feel)" isn't about sex—well, at least, the video wasn't. Director Paul Hunter told GQ in 2012 that the video was actually about eating his grandmother's cooking after church. "Most people think the 'Untitled' video was about sex," Hunter told the magazine. "But my direction was completely opposite of that. It was about his grandmother's cooking. Think of your grandmother's greens, how it smelled in the kitchen. What did the yams and fried chicken taste like? That's what I want you to express." D'Angelo agreed with that sentiment later in the piece.

- Madonna's "Like a Virgin" may seem like the ultimate document to femininity, but songwriter Billy Steinberg was the guy who wrote those words, and he wasn't always sure that they were actually meant to be for a female singer. Nor did he think another song of his, "I Touch Myself" by Divinyls, was obviously meant for a female singer. "I mean, it might sound silly to think of a guy singing those songs," Steinberg explained to SongFacts. "But when I wrote those lyrics I wasn't thinking that they were intended just for a woman to sing. But I guess maybe they were better for a woman to sing."

- Eddy Grant's "Electric Avenue," outside the context of its 1982 release, sounds like a really awesome night on the town. Sorry to tell you that it's actually about a really awful night on the town—specifically, the 1981 Brixton Riots, a wide-scale riot in the U.K. that involved as many as 5,000 people and led to dozens of injuries and arrests. The riots actually have a number of parallels with the more recent Ferguson protests in the U.S.

Translating foreign-language pop into American

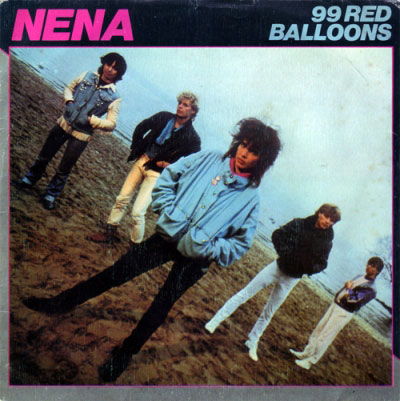

The balloons originally weren't red.

For a generation of kids who didn't grow up during the Cold War, the meaning behind the classic '80s protest song "99 Red Balloons" perhaps isn't so clear now. But in its day, the German tune packed a pretty powerful message during an era when the Berlin Wall was still up. The tunefulness of the track actually translated pretty effectively across borders, but the tune still needed a rewrite for the U.S. market. And that led to a problem of syllables—the song's original title, "99 Luftballons," essentially translates to "99 Air Balloons," or more correctly "99 Balloons."

So rather than lose a syllable, the balloons became red.

As that example shows, the U.S. has a spotty record with giving songs sung in foreign language the right level of appreciation. Another, better example: A Japanese romantic ballad topped the Billboard charts in 1963. The problem is that they called the Kyu Sakamoto-sung tune "Sukiyaki," which is the name of a popular type of Japanese soup.

The song had as much to do with soup as Hozier's "Take Me to Church" has to do with organized religion.

"Radio DJs decided that no one could pronounce 'Ue o muite arukou,' so they picked a Japanese word, seemingly at random, that they thought American consumers might be familiar with," the blog Eurasian Sensation explained in 2010.

The result is that a prime opportunity for introducing Americans to a piece of Japanese culture—particularly during the post-war era, when something like this would have been of value—was somewhat trivialized in an effort to make it palatable for American ears.

(The song, in fact, was actually a veiled tune about the disappointment of the failed protests against the U.S. military presence in the country. Which makes the name issue extra weird.)

On the plus side, the disco-funk band A Taste of Honey saw the value of the song's original meaning, and lead singer Janice Marie Johnson rewrote it in English with the approval of the copyright holders. Since then, the song has hit the Top Ten in the U.S. twice more.

Not a bad run for a song technically called "beef stew."

"Songs and poems, in some sense, lie between conversational speech and a foreign language: we hear the sounds but don’t have the normal contextual cues. It’s not as if we were mid-conversation, where the parameters have already been set."

— Maria Konnikova, a writer for The New Yorker, explaining the linguistic reasoning behind mondegreens, or misheard lyrics. In other words, our frame of reference is why we hear "bathroom on the right" rather than "bad moon on the right." Konnikova notes that there's even a scientific theory that explains this phenomenon, Zipf’s law. The law emphasizes that the frequency in which we hear a phrase affects how we interpret it.

How Christian (er, spiritual) rock bands straddle the secular line

Here's a dirty little secret about Christian contemporary music that goes mainstream: There's a good chance that the song you're listening to is probably a love song about Jesus.

Example: "Hanging by a Moment," the breakout hit for the post-grunge band Lifehouse, is actually an imagined conversation with Jesus. Likewise, their later hit "You and Me" is very similar in conceit.

But knowing that this Jesus talk is likely a turnoff for secular audiences, the band is very careful about the wording in its songs—and while the band initially found buzz in the world of CCM, it went out of its way to emphasize that it wasn't Christian—rather, it merely has Christian members.

"My music is spiritually based, but we don't want to be labeled as a 'Christian band,' because all of a sudden people's walls come up and they won't listen to your music and what you have to say," singer Jason Wade once said in an interview.

In other words, he doesn't want you to tune his message out just because it talks about religious things. It's a tough line, but Lifehouse wasn't the first band that's tried to straddle it by any measure. (Nor were they the last. The Fray has dealt with similar issues over the years.)

Lifehouse—and bands like them—were really just following the template of Amy Grant, who savvily became a major pop star by performing secular tunes, most famously the 1990 hit "Baby Baby." (That song isn't about Jesus, by the way: she wrote about her new baby.)

However, there's one difference: When building an audience, Grant had to deal with stigma from both sides of the musical world. She had to convince secular fans that she had a broader cultural perspective than modern hymn-singing. (She managed to do that.) And, on the other side, she was vilified by some for supporting the "secular" world. By reaching the theoretical mainstream and potentially getting a bigger audience for her message than she might have had on its own, it only caused those most invested in that message to question her devotion to it.

One of the worst things to be as a creative person is pigeonholed. In that context, you can understand why a band like Lifehouse might reject the "Christian band" label. They saw what happened to Amy Grant.

I hope this email makes you think a little harder about the stuff you hear on the radio, about the possibility that those three-minute ditties are really multi-layered onions. We don't analyze the culture around us enough.

That said, there's always room to overanalyze. Infamously, Feministing contributor Verónica Bayetti Flores found herself subject of a massive backlash in 2013 when she claimed that Lorde's song "Royals" was racist.

We've had 18 months to let that controversy die out, and in some ways, analyzing it from a distance points out that it may have been more interesting than it might have first seemed.

Flores' thought process, in some ways, was like the op-ed version of a mondegreen. She heard the song in the context of her own life experiences, which were different from that of a teenage girl who lived in New Zealand and heard nothing but context-free hip-hop coming from the United States.

Maybe Flores was right to bring up her concerns, maybe she was wrong. But she nonetheless proved a basic truism: At some point, a culture-crashing song switches ownership. It's no longer the singer's, nor the songwriter's. We make these songs our own.

Now excuse me while I kiss this guy.

:format(jpeg)/2018/04/gheyikpftu9zf0gazw1e--1-.gif)

/2018/04/gheyikpftu9zf0gazw1e--1-.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)