Walk on the Vinyl Side

Before Rock & Roll Hall of Famer Lou Reed became an rock icon, he cut his teeth on producing soundalike recordings. People are still making 'em today.

I'm waiting for my break

Pickwick Records was as weird a record label in the conventional sense as the Velvet Underground was a weird band in the avant-garde sense.

And Lou Reed, who once recorded a song where he and a bandmate shouted indecipherable poetry into a microphone, split the difference. Before he became known for his ties to Andy Warhol and David Bowie, and before he decided to record an entire album that involved him screwing around with his amp, he was recording silly dance records for a record label that was designed to score cheap hits out of whatever was popular.

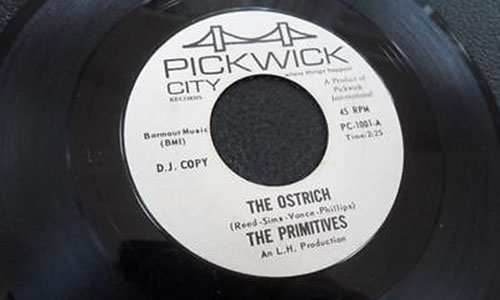

The Beach Boys had "Surfer Girl"; Reed and his band The Beachnuts had "Cycle Annie." Chubby Checker had "The Twist"; Reed and his band The Primitives had "The Ostrich."

The songs were cheaply recorded, but this was actually a great thing for Reed, notes band biographer Michael Sandlin—because it introduced him to both the sounds and the people that would define his career.

"For Reed, the Pickwick gig would prove to be short-lived. Lou, however, honed his craft as a songwriter and became extremely efficient in the recording studio," writes Sandlin. "From the ashes of this Pickwick experience sprung relationships with John Cale, Tony Conrad and drummer Angus MacLise. Lou's influences at the time—marked by both a love of rock n roll and the free-jazz aesthetic of Ornette Coleman—found an appropriate counterbalance in the radical postmodernist and neo-classical influences of the other three members."

That combination of odd influences is why Lou could write great pop songs about topics that were considered taboo at the time.

"I picked up a number of them unknown singers and used them to make children's records. Later on some of them went on to fame in the adult music field."

— Pickwick Records founder Cy Leslie, in a 1958 interview he did with The Associated Press. Leslie's path into the music industry was incredibly weird. After serving in World War II and wishing he could talk to his loved ones, he created a product that could do just that: talking greeting cards. That was the start of his drug store empire. From there, he got into the record business and started producing albums on the cheap—his company first started by producing children's records that he sold for a quarter at drugs stores, earning Leslie the odd title of being "the King of the Kiddie Records." Eventually, Pickwick stopped making kid's records and, with the help of major-label contracts, started making straight-up budget records. This man, however indirectly, created the atmosphere that build Lou Reed.

Five facts you probably didn't know about vinyl records

- Before vinyl records became commonplace, the substance shellac—a glossy lacquer made from bug secretions—was used. The reason vinyl eventually took over was because it was a stronger material that sounded better. One of the early uses for vinyl was through the use of "transcription records," large 16-inch discs that radio stations initially used to distribute syndicated programs.

- Most techies are probably aware that cassette tapes were once used as storage devices, but what you might not be aware of is that, at least for a time, vinyl record flexidiscs in magazines were used to distribute software.

- Record needles were once inexpensive and made out of steel, but as vinyl records have become more of a luxury item and quality became more of an issue, needles are increasingly made from artificial sapphire and diamonds.

- Voyager’s Golden Record, a copper LP included on the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecrafts back in the 1970s, includes 90 minutes of music—but it also has photographs encoded. Some of the photos are bizarre (a woman licking ice cream, a man eating a sandwich), but you gotta remember that aliens are gonna be looking at these photos and have no idea how humans function.

- If you ever wondered whether vinyl records could be read with lasers like CDs, the answer is yes. Not that many people do it. The Japanese manufacturer ELP sells laser turntables, but because of the devices' rarity and size, you'll be paying a pretty penny for them. The devices, despite being around for more than 25 years, cost as much as $14,000.

They're still making cheap soundalike records today—here's where

The Beatles aren't on Spotify, but that's OK. There are enough artists covering the band's songs that you probably won't even miss them.

As we pointed out earlier this week, search engines can have a massive influence on the way that we think. They can erase prominent people with the wrong name, and they can lead us to places where we weren't actually headed.

In most cases, these artists and producers practicing a form of arbitrage. They're leveraging someone else's mistake or inability to properly monetize their music in an effort to take advantage of the suckers. They're creating music for bad spellers.

In 2012, a soundalike cover of a Maroon 5 hit, "Payphone," hit the music services before the band had a chance to release their own version—and that version hit No. 9 on the British charts first, leading to controversy.

Sound crazy? Well, it's getting crazier. Last month, Cuepoint's Shawn Setaro noted that the phenomenon was becoming more prevalent than ever. In the age of Pro Tools, you can get really close to the same sound. Some artists who work on these soundalike covers—like modern-day Lou Reeds—say that some artists creating original music are even doing straight-up rips of other tunes, with only minor changes and new lyrics.

“[That album] is like, holy crap, I don’t know if that’s cool. … There’s a line to be crossed or not crossed when you deal with sampling versus replaying things note for note, and then creating original music,” drummer Charlie Zeleny told Setaro of Meghan Trainor's album, Title.

Maybe that "Blurred Lines" lawsuit might change things up on this front? There's a question worth pondering.

Lou Reed's rise to underground prominence was the direct result of an unusual confluence of retail huckery and a closed path into the music industry. In the 1950s and 1960s, infrastructure was hard to come by. Now, there's more infrastructure than ever … and we're back to soundalike records again.

Is it possible that the next Lou Reed is playing on cash-in Spotify record or on a Kidz Bop record somewhere? You betcha. He or she may not get the, uh, experience that Reed got in mid-1960s New York City, but they might just be recording guitar parts for a Maroon 5 song or dropping vocals on a rendition of "Royals."

The big difference, of course, is that Lou Reed was doing it for the experience—and these new artists are doing it for the SEO.

:format(jpeg)/2018/11/hmzvo9yysjxcwsolyldb.gif)

/2018/11/hmzvo9yysjxcwsolyldb.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)