A Phone Book For Computers

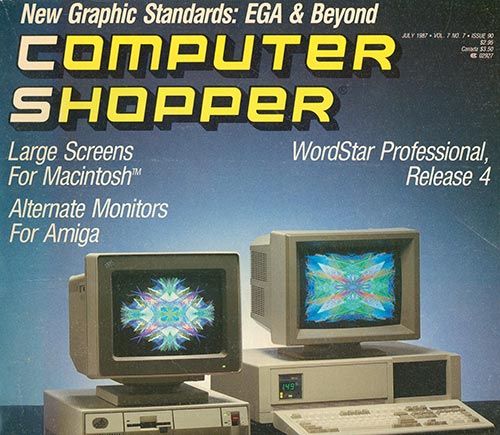

Before we used the internet to find computer parts, we used Computer Shopper, a magazine that commonly had over 800 pages in a single issue. Really.

A thousand pages of PCMCIA cards and minitower cases

You know how today, you can buy pretty much anything you want for a computer or—let's face it—anything else on Amazon?

The world was not like that in the early 1980s. With computing a new field and many more parts required to keep a computer running at the time, it became important to have a way for enthusiasts to find the necessary parts for early IBM PCs or Atari 400s. And with numerous manufacturers at the time—some of whom didn't last very long—but limited room inside of Radio Shacks or even dedicated mom-and-pop shops, direct sales became an important early model for computer sales.

Today, most computing publications either aim for the enterprise or the home. Computer Shopper never really aimed for either during its peak—instead, it became a key source for information for technical enthusiasts, what you might call the prototypical maker movement.

Some of those makers started companies that advertised in Computer Shopper—most famously, Dell, which excelled at the direct sales model the magazine encouraged. And because there was always room for more ads, the books sometimes topped the 1,000-page mark. No, really.

"He's somewhat of a visionary. He said, 'This is the wave of the future. People are going to buy and sell these things just like they trade baseball cards.'"

— Louis Cianfrogna, a onetime lawyer for Patch Communications, discussing the founding of the company's signature product, Computer Shopper. The magazine was the brainchild of Glenn Patch, a photography fan who had started a similar classified publication for that niche. Patch had pitched his idea for a computer circular to Cianfrogna and others in the early 1970s, but didn't get around to launching it until 1979, a point when computers were just starting to break out of the hobbyist space. The computer magazine nearly didn't happen—Patch had run out of money for Shutterbug Ads, but a loan from a friend kept the circular alive at its weakest point.

Five interesting facts about Computer Shopper

- Initially, the magazine did not have much in the way of editorial content at all—it was basically a never-ending ad circular. This changed after an early entrepreneur in the computer space, Stan Veit, wrote a letter to the publication criticizing its weak news value. The letter led to Veit taking over as the magazine's first editor-in-chief. Really.

- In a 1999 column written by Veit, he notes that the publication thrived at a time when many other computer publications were folding. The reason for this, he explained, was because it was suddenly the only source readers could use to find information about obscure, unsupported computers.

- Despite its immense girth in the '80s and '90s, the magazine was not thick enough to stop a bullet. And yes, some editors of the magazine tested this out, according to former senior editor Dan Rosenbaum, who said it was a "general surprise when we discovered that even the thickest Shopper couldn't stop even a .22—but a .45 made a spectacular pile of newsprint confetti."

- Prominent tech journalist Harry McCracken, currently with Fast Company and formerly with Time, noted that he started his career launching a competing magazine called Computer Buying World that quickly crashed and burned. "If you weren’t there, you can’t imagine how [dispiriting] it was to try to beat that magazine at its own game—or how silly, in retrospect, to even try," he wrote in 2013.

- While the original magazine—which saw numerous owners over the years—ended its print edition in 2009, a British magazine of the same name is still going strong.

The billionaire that Computer Shopper (and cattle farms) created

The gateway to Ted Waitt's fortune was his grounding in rural culture. He had the same idea that Michael Dell did at roughly the same time, but he managed to do it with a better sense of humor and a little more flair.

Waitt, who founded Gateway 2000 in September 1985—less than two years after Michael Dell founded a similar PC clone company in his dorm room in Austin, Texas—got his start in Sioux City, Iowa, initially building the machines thanks to $10,000 in seed money from his grandmother. Waitt and his business partner, Mike Hammond, took advantage of the fact that Texas Instruments was no longer supporting its proprietary machines, and created hardware add-ons that helped make them IBM-compatible.

Soon after, the company switched to selling PC clones of its own. Within five years, the company was racking up a billion in sales per year—more than even Dell. But around two decades in, it had been sold of for a fraction of its peak market value to the Taiwanese computing giant Acer—with its roots long uprooted.

Two things helped Waitt's company, Gateway 2000, stand out: The aggressive use of advertising in Computer Shopper, and marketing that featured the black-and-white piebald pattern—the kind that you would usually see on a cow located near Waitt's hometown of Sioux City, Iowa. The unusual marketing stood out among the straight laced ads promoting machines that were essentially fighting to be the best copy around.

By focusing on a different kind of copy—ad copy—Gateway managed to keep its mojo strong during the early Windows era.

Was Gateway 2000 too innovative, too early?

During its '90s heyday, Gateway did a number of things that eventually caught on in the broader computing market:

Shrank the laptop. The company produced a tiny laptop called the Handbook in 1992, more than 15 years before netbooks first gained popularity and nearly two decades before the iPad became common. For their size—the mini-laptops weighed just two and a half pounds—and era, the devices were fairly powerful. (Fun fact: Current Fox News contributor Brit Hume co-wrote one of the first reviews of the device.)

Produced a smart TV. In 1996, Gateway produced a 32-inch television with a built-in computer called the Destination, the first time that a TV and computer had been combined with an eye on the living room. They weren't the last, but the massive price tag at the time—it was selling, in various configurations, for as much as $4,700—made the device a niche item at best.

Created their own dedicated stores. Before Apple and Microsoft got into the storefront game, Gateway got a leap on the concept with their Gateway Country brand, a store that basically embraced the same idea the Apple Store did—just put the computers out there, so people can try them before they buy—two years earlier. The suburbia-based stores expanded aggressively, which was basically the opposite of Apple's more gradual approach, and the stores closed down within a few years.

But as the company grew, these kinds of innovations eventually faded from view, and by the early 2000s, Gateway was just another anonymous big-box computer-maker—eventually ditching its direct-sales model entirely in favor of the retail strategy favored by one of its acquisitions, eMachines. The cow spots were still there, but the heart behind them was gone. Waitt, in a 2007 interview with the Sioux City Journal, admitted the company's move to California was a mistake.

"It was much more money-oriented. It was much more short-term oriented," Waitt said of the move. "And there was different leadership in place at that time that incentivized that—and changed the company, I think, indelibly."

Gateway's still around (without the 2000), but they don't sell the direct-order machines that were their claim to fame—their parent company Acer has that one covered, thank you very much. And despite having essentially invented the netbook, they're known for essentially selling commodity desktop machines like this one.

On the plus side, at least Ted Waitt's still rich—and, as a philanthropist, is doing some impressive things with his wealth.

Closing out, I just wanted to switch gears and briefly reflect on another recent Tedium topic that had its heyday in the early '90s: Columbia House. The firm's parent company this week announced that it was filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, blaming the rise of streaming for both music and movies for the eventual demise.

"This decline is directly attributable to a confluence of market factors that substantially altered the manner in which consumers purchase and listen to music, as well as the way consumers purchase and watch movies and television series at home," said Glenn Langberg, the director of Filmed Entertainment, Inc., was reported to have said in court papers.

In other words, the internet destroyed the business. The company plans to cut itself up into little pieces and hopefully sell the important parts for scrap. Something tells us, however, that—like Computer Shopper vendors circa 1992—all the important assets went away a long time ago.

The only truly valuable thing left is its story.

:format(jpeg)/2018/04/prrxfxydibznr0a3xima.gif)

/2018/04/prrxfxydibznr0a3xima.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)