Tape Deck Heart

Vinyl records are getting all the buzz these days, but what about magnetic tapes? They're just as quirky—whether we're talking VCR or reel-to-reel.

2010

Get out your wallet: You can still buy reel-to-reel tapes in 2015

Now, let's be clear here: Cassette tapes are not the only way one can enjoy tape-based music.

When Neil Young is waxing poetic about the quality of sound and why you need to buy a Pono audio player, he's talking about the crystal-clear sound he hears when he's listening to albums on high-resolution reel-to-reel master tapes used at most traditional music studios. He may be selling you a hill of beans, but he knows what he's heard in the studio, and Spotify and Apple Music could never freaking compare, ever.

So, what's the alternative? Well, if you happen to own a reel-to-reel tape player in your space-age pad, there's always the option of collecting music sold in the same format as many albums were recorded. Over on eBay, you can get reel-to-reel tapes of popular records from the 1960s and 1970s for about the same price as an LP from the same era.

But if you're a vinyl-head, you know that it's common for labels to release super-fancy re-releases of critically acclaimed albums. Earlier this year, for example, the indie label 4AD created a minor amount of controversy after it decided to release a box set of Red House Painters albums on limited edition bronze-colored vinyl, only to sell out almost immediately. They decided, eventually, to also release the records on regular-colored vinyl to appease all the sad saps out there. (Speak to me, Mark Kozelek!)

You might be not really wondering—is anyone doing the same thing for reel-to-reel fans?

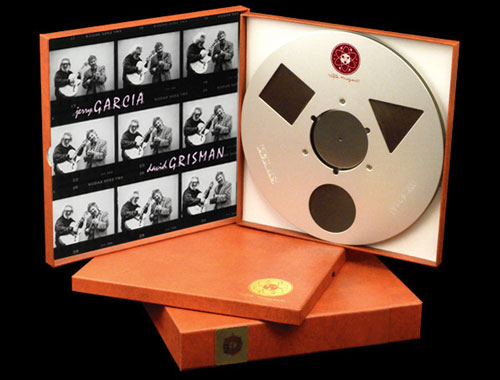

The answer is yes. The Tape Project, an enthusiast effort, has been re-releasing popular older albums on reel-to-reel tape over the past few years. The albums tend to vary from obscure-but-influential jazz classics to Linda Ronstandt's most popular album.

"We don’t expect that this tape project will replace any of your other favorite formats, so we see no need to dwell on the drawbacks of any other format. Suffice it to say that we don’t offer an 'analog-like' listening experience," the website states. "We are offering a chance to have in your own listening room an actual analog listening experience as close to the original master tape as practical."

But one thing you might notice about these albums is that they're freaking expensive—we're talking week's pay expensive for many folks. (They emphasize that the reason for this is due to the fact that producing reel-to-reel albums in this fashion is incredibly expensive. Yeah, we bet.)

If you can afford to spend $450 on Creedence Clearwater Revival's fourth album, it may be a real treat. Most people, however, are likely to stick with Apple Music. Sorry, Neil.

Five interesting quirks that tape-based mediums have

- Strongly linear nature. When it comes down to it, the biggest downside of tape as a recording medium is the fact that it only works in two directions, and moving between different parts of a tape takes a significant amount of time (as anyone who has returned a Blockbuster tape can tell you). Despite this, this didn't stop companies from trying to stretch the tape medium—in fact, some startups even tried to make video games for VCRs in the '80s.

- Sensitivity to moisture. Here's one that you probably haven't run into too often. At certain levels of humidity, VCRs and camcorders are susceptible to condensation of dew and other types of moisture, and a moist tape head can cause serious clogging problems. (The issue was significant enough that it led to video CDs, the precursor to DVDs, becoming more popular in Asia than VCRs.) So as a way to avoid this, device manufacturers have taken to "dew warnings" that flash on moisture is detected in the device.

- Sensitivity to heat. In the mid '80s, cassette manufacturers had to redesign their products because an unusual problem kept creeping up: People would leave their Culture Club tapes inside their cars, often in the glove compartment or on the dashboard, and the tapes would eventually start melting. CDs, which are made of polycarbonate, don't have this problem because they have a far higher melting point.

- Compatibility with credit cards. The magnetic stripes used on credit cards are based on the same technology as tape players are, which meant that when Square's card reader first came out in 2011, it allowed for some fascinating hacks by enthusiasts, including one guy who was able to decode the data on his own credit card, and another guy who figured out how to play music on his iPod Touch using a reel-to-reel tape deck, his Square reader, and a little ingenuity.

- Ability to store lots of data. While it's way more common these days to put information on flash drives and hard disks than tape cartridges, the usage of tapes to store data never really went away—in part because the medium is particularly good at securing such data over long periods, which makes it awesome for enterprise and cloud computing uses. Earlier this year, for example, IBM and Fujifilm announced the creation of a tape cartridge that can hold 220 terabytes of data. To put that in perspective, the largest hard drive currently on the market is a modest 16 terabytes.

Why some reel-to-reel tapes need to be "baked"

On the digital preservation side of things, magnetic tape is seen as one of the best ways to protect content over a long-term period—specifically if that tape is the high-density stuff that you'll find in the enterprise world. (You'll want to convert that data from analog to digital, though.)

In comparison, hard drives and flash drives have a limited shelf life and are harder to protect from the elements of time. That said, magnetic tapes aren't without their problems.

The biggest such problem can be blamed on the tape manufacturers themselves. In the 1970s, some manufacturers decided to change the adhesive used to apply magnetic tape to plastic film. At the time, the tapes worked fine, but the folly of this approach showed over time, when an effect called "sticky-shed syndrome" began to surface. Essentially, the binding used on the tapes attracts moisture—which separates the magnetic tape from the plastic backing, then disintegrates entirely.

If you play a sticky-shed tape on a reel-to-reel player, the results will sound scratchy or even unreadable, and can leave dusty specks on the tape head. Not fun.

(This doesn't affect cassette tapes, by the way, but then again, you melted all your cassettes by leaving them lying around in your scorching-hot vehicle.)

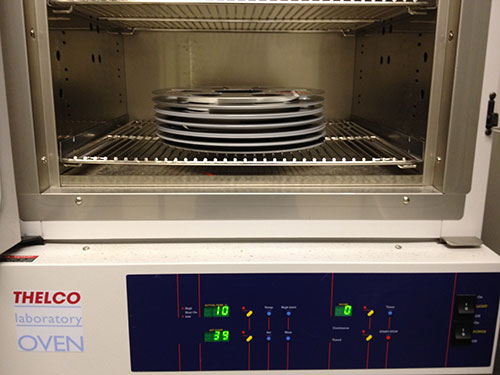

Trying to salvage these tapes isn't the easiest thing in the world, but it can be done. NPR—which has roughly four decades of reel-to-reel tape to protect—is one of many advocates of "baking" tapes to re-adhere the tape the plastic backing. The radio network heats up tapes inside a special laboratory oven at a temperature of 125 degrees fahrenheit over an 8-hour period. The end result is then playable on a reel-to-reel player … but only for long enough to convert the recording to another medium.

"Baking the tape at a low temperature in our special laboratory oven temporarily restores the integrity of the tape," explains NPR's Lauren Sin. "However, baking is only a temporary solution to counteract sticky shed."

In case you'd like to "bake" some tapes of your own, it's not exactly an easy process, writes audio-restoration expert Graham Newton. You need a thermometer to ensure that you get the exact temperature needed, and you basically want a relatively low, dry heat to get the best results. Conventional ovens may work, but they have to be thoroughly tested.

Newton has one important tip, though: "DO NOT ATTEMPT TO USE A MICROWAVE OVEN… they are totally inappropriate for the job, and may be dangerous if used with metal reels."

Save the microwave for the Pop Secret.

The degraded quality of tape as a result of sticky-shed syndrome is largely a destructive problem that hurts the ability for archivists to protect outdated material. But the effect, occasionally, can add something new to the recordings.

Experimental musician William Basinski—known for his tape loop-heavy compositions—found this out the hard way when he tried to salvage some old recordings that he created in the 1980s. After letting the tapes sit around in boxes for years, he tried saving the material to disk so he didn't lose his old material.

He was too late: The tapes were literally breaking apart at the seams—destroying the shape of the music he had created decades earlier, but adding its own wrinkles in the process. The decay, in many ways, made the music more interesting.

He finished converting his tapes to digital on the morning of September 11, 2001. The resulting recording, which he called The Disintegration Loops, provided an unsettling soundtrack for the events which took place in New York that day—events that Basinski and his neighbors could witness in real-time from their Brooklyn apartment building.

As daylight began to fade into night, Basinski grabbed a video camera and recorded what was happening from the roof of the building.

Suddenly, his work of accidental creativity had new meaning.

:format(jpeg)/2018/11/onwi6jmffy1ij8un8qxf.gif)

/2018/11/onwi6jmffy1ij8un8qxf.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)