Format War Footnotes

Laserdisc, anyone? How about HitClips? And what's the deal with slotMusic? All these media formats were made for some reason. We're not sure why.

“The world will little note, nor long remember …”

— A quote, made by Abraham Lincoln during the Gettysburg Address, that was quoted in a commemorative video created by RCA in honor of the Selectavision VideoDisc. The vinyl record-style video format had the misfortune of being released in 1981, after the release of both VHS and Betamax VCRs—despite the fact that RCA had created the Capacitance Electronic Disc technology on which the device is based back in 1964. The quote was at the very end of the final video created for the analog movie format, which is basically an elaborately produced obituary for a device that few people owned. You can, of course, watch the whole thing on YouTube, and learn more about the ill-fated video format over this way.

Five misguided attempts to replace the MP3 with a physical alternative

- Tiger Electronics’ HitClips product competed directly with early MP3 players with incredibly low-quality clips of popular songs of the era. Somehow, despite only offering barely listenable one-minute clips of pop songs, Tiger Electronics sold $80 million worth of HitClips during the TRL era. Want to spend $25 on a one-minute Sugar Ray clip? Here ya go.

- Sony’s Minidisc players were a lot better for portable music than cassettes and handled shakiness a lot better than portable CD players did. (I owned one around 2000 or so. Before the iPod, it was actually great.) And as it supported data files, it offered the best of both worlds for mixtape fans and digital downloaders. The problem? Instead of embracing MP3s, Sony kept pushing its own DRM-laden ATRAC format, and the first version of its digital Hi-MD format didn’t natively support MP3s. Sony let fears of piracy kill the format’s legitimate chances to compete with the iPod. Oops.

- Two attempts at a high-quality take on the CD player, DVD Audio and Super Audio CD, created a tiny format war around the turn of the century, just as people were eyeing getting rid of discs altogether. As it turned out—as should have been obvious by the rise of HitClips—people didn’t really care about higher quality audio. They really wanted audio that was incredibly portable, but sounded good enough.

- Eventually, flash memory maker SanDisk got the great idea to distribute high-quality MP3 albums via flash cards, with its resulting slotMusic idea effectively combining the best parts of HitClips and Minidiscs into something reasonably useful. But not too useful: Upon its launch, tech critic Om Malik wrote that the devices were destined to fail. He was right.

- Oh, and Neil Young’s Pono. Not sure what he’s thinking with that thing.

$337M

The BBC created a project to preserve history on a format that nobody uses

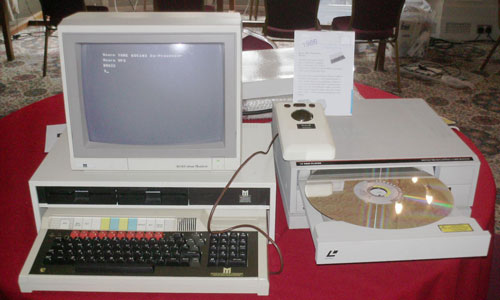

In a way, the BBC couldn’t have picked a worse time to launch its Domesday Project. Put together in honor of the 900th anniversary of the Domesday Book, an early British census, the project was a bit of a boondoggle because it tried to push the boundaries on multimedia technology a few years before the market had settled on standards for such multimedia.

The result was that trying to recover the data from the project, which hit schools in 1986, was arguably as hard as trying to keep a 900-year-old book alive.

How was the BBC supposed to know that we wouldn’t be using Acorn computers that rely on a nonstandard variation of the Laserdisc format five years after its release, let alone three decades?

Now, to be fair, the broadcasting organization realized that its task at hand—gathering all the various forms of life in Britain in the 1980s—would be extremely difficult to do through television, which is why they went to Philips to develop its Laservision Read Only Memory (LV-ROM) format. The result works something like a combination of a CD-ROM and Laserdisc, combining an analog track for audio, some video, and a data track that can manage around 300 megabytes of space. The problem was, CD-ROMs didn’t exist when the project began.

“The BBC originally planned to make a series of TV documentaries on Domesday, but soon found it faced the same problem as King William: although there is no shortage of information on life in Britain, there is difficulty in collating it for easy access,” The New Scientist explained in 1986.

As for Acorn, they were roped in because they were already producing BBC Micro computers, which were heavily used in British schools at the time. The system was stretched so far beyond its limits by the Domesday Project that Acorn had to build a brand new kind of computer to even support the disks. And even then, it barely even worked.

“Unfortunately, the Acorn computer lacks the memory to store all the retrieval software at the same time,” the New Scientist article continued. “So the Acorn has to compromise by holding a ‘kernel’ of software permanently in memory and then loading smaller chunks of the program as they are needed. Inevitably, this will slow down the system.”

Considering how well it worked then, just imagine how well it works now.

How the techies saved an early digital artifact

Unlike the Domesday Book, the Domesday Project was in serious threat of fading away after only a few years—a stunning loss of data—due to some unfortunate format decisions.

“The information on this incredible historical object will soon disappear forever,” broadcaster Loyd Grossman warned in 2002, according to The Guardian.

Fortunately, digital archivists Jeffrey Darlington, Andy Finney and Adrian Pearce worked like crazy to attempt to save the project around that time—a process that involved building an emulator that replicated the technology from Acorn’s computer, converting images from the original discs to JPG format (a format that didn’t become common until after the project was made), and converting the original videotapes to a digital format. The latter solution was only decided upon after realizing that converting the video directly from the Laserdisc created low-quality results.

Had they waited a few more years, they could have missed a narrow recovery window.

“Some original systems and hardware components were still available and could be made to work, but the systems were fragile,” the trio wrote. “Wear between the videodisc drive spindle and the disc has caused the loading of the disc to be a delicate operation on most systems.”

All that work went to good use in 2011, when the BBC relaunched the project as a website. Hopefully it lasts a little longer this time.

The Laserdisc format itself, unlike the Selectadisc VideoDisc, still has something of a cult following for those in the know—it didn’t win the video market in the U.S. or much of the Western world, but in Asia, it was freaking huge. As a result, it still has currency among anime fans.

And Laserdiscs, as a format, went in some weird directions. Laserdiscs were one of the first formats available to consumers that allowed for on-screen karaoke lyrics for example. And in the mid-80s, one company made a video jukebox using Laserdiscs to show music videos. When Commodore decided it wanted to compete with HyperCard, it created its own version of the software that allowed users to control Laserdiscs.

Finally, they proved influential in the world of video games, where Dragon’s Lair used Laserdiscs to great effect.

These days, we do all this stuff in the cloud.

:format(jpeg)/2018/11/rrqg0ckkiko71opybjde.gif)

/2018/11/rrqg0ckkiko71opybjde.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)