A Magazine You Can't Bend

For a brief time in the '90s, publishers thought that CD-ROM magazines were the future. But, as it turned out, readers were more interested in the internet.

$2,500

Five examples of the kind of content you'd find on a CD-ROM magazine

- Previews of upcoming CD-ROMs: In case you weren't already impressed enough with the CD-ROM inside your CD-ROM drive, these magazines would preview much better CD-ROMs you should buy instead. Here's an example of what this sort of intensely meta offering looks like.

- Mystery meat navigation: You remember how some early websites had designs where you never knew where to click? CD-ROM menus were like that, multiplied to 11. Watch this poor guy attempt to click through this Nine Inch Nails story on the first issue of Substance Digizine. He has no clue what to do!

- New age music: Considering this is the platform that brought us Myst, it only makes sense that one of the CD-ROM magazines out there, NautilusCD, had a deal with the record label Windham Hill, which had built a name for itself as the new age label du jour.

- AOL installers: It was the '90s, and you had a CD-ROM. What did you expect?

- For some reason, wire stories.Medio Magazine, which promoted its offering with the tagline "like a new encyclopedia every month," felt like there would be an audience for a periodical-style version of Encarta, which according to Variety, was loaded with old Associated Press copy, proving to the world that Google couldn't come along soon enough.

The founder of Maxim spent $5 million trying to make CD-ROM magazines happen

It makes a lot of sense that Felix Dennis was the guy behind the magazine Maxim. The British publisher, who died in 2014, was prominent enough to receive an out-and-out obituary in The Economist, but whose reputation was such that the obit almost immediately called him "a hedonist" and spoke of Dennis' masterful ability to spend millions of dollars on all sorts of excesses.

Almost immediately after starting his career with the counterculture magazine Oz, Dennis went to jail on an obscenity charge, only for John Lennon to step in and record a charity single to help pay the magazine's legal fees.

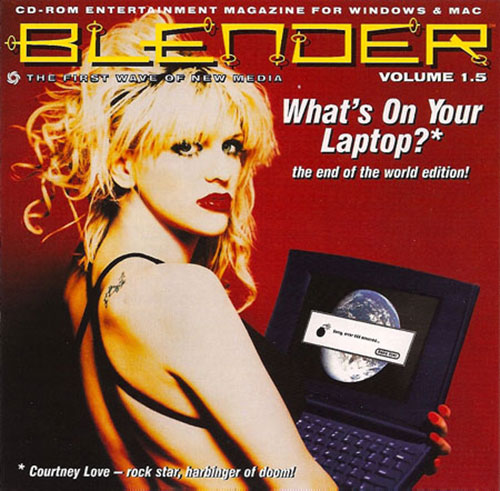

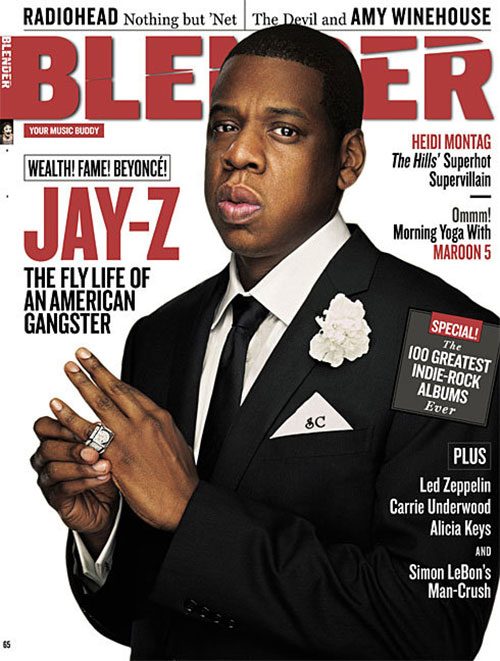

To put it lightly, Dennis was a bit of a risk-taker, which is probably why the idea of a CD-ROM magazine appealed to his sensibilities. In 1994, his company Dennis Publishing launched the first edition of Blender, a monthly pop-culture magazine designed to appeal to the multimedia crowd.

Star power was not lacking from the magazine, which offered a nice halfway point between MTV-style interviews and print. Early issues featured interviews with Bjork and Devo, and numerous vignettes featuring a pre-Daily Show Jon Stewart.

"Hey you're watching Blender," TMBG's John Flansburgh said at the start of one video. "It's interactive! Click on my face! Click on my damn face!"

Dennis invested $5 million of his money into the effort, hoping to see some dividends. He did not, with the initiative failing to sell enough copies to recoup its operating costs.

"I loved it. So did the rest of the media. We won a zillion awards. The designers and editors were fêted and rivals began to prowl around the corridors wondering if Blender meant the death of ink-on-paper magazines. They needn't have worried," Dennis wrote in his cheekily titled book How to Get Rich.

The CD-ROMs stopped rolling off the presses in 1997. (You can find some copies of the CDs on the Internet Archive, though you're on your own in getting them to actually run.) As a brand, however, Blender didn't die right away. At first, Blender tried to live on as an interactive television app for Mac and Windows users, but that didn't catch on either. In 2001, however, Blender returned in its most successful form—a traditional print-and-digital music magazine. Prior to the magazine's relaunch, loading up Blender.com on your browser brought up this fairly self-aware comment on the nature of the CD-ROM magazine.

"Blender pre-dated and predicated much of the interface design and high-bandwidth technologies available today, but after three years our distribution model had clearly been eclipsed by the Internet," the website stated, according to the Internet Archive.

Not that Blender survived to the present day. The magazine stopped publishing in 2009 and the website now redirects to Maxim.

There will be no charity singles written in its honor.

"Quick: What are the most compelling features of a magazine? Exactly: You can take it to the john. You can throw it under the desk when your boss walks in. You can rip off the cover and post it on the wall or rip out that stink bomb of a perfume ad and throw it away. In short, a magazine is disposable, portable, malleable."

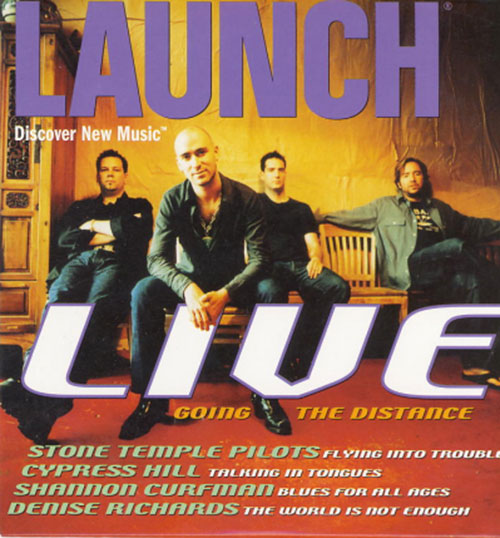

— Entertainment Weekly critic Ty Burr, basically nailing a major problem with CD-ROM magazines in a roundup that reviewed most of the popular ones of the era. (LAUNCH had yet to, uh, launch at the time Burr wrote his piece.) To be honest, this problem wasn't really solved with digital magazines until the point that the smartphone came along and was good enough to produce a magazine-style experience on a tiny screen.

CD-ROM magazines figured out one thing online journalism never has

The downfall of CD-ROM magazines, when you get down to it, is very similar to the issue that faced digital magazines upon the launch of the iPad—to put it simply, they're designed to be single-source media outlets at a time when we read dozens of media outlets a day.

Unlike when The Daily or any of the Apple Newsstand apps appeared, however, this wasn't a foregone conclusion. The New York Times had yet to appear online in 1994. Heck, Wired hadn't even unleashed the banner ad onto the world until September of that year. It was entirely possible that the future of journalism was going to involve a handful of in-depth experiences with multimedia each week, much like with magazines.

What publishers didn't anticipate, however, was that consumers would become omnivores of journalism. Instead of eating one or two large meals a day, we forage for information online—and have a lot of shallow experiences with tiny pieces of content every minute of every hour of every day.

Websites that better adapted to these kinds of consumption habits—Slate and Salon, which first came on the scene in 1995, and Pitchfork, which launched the next year—are still with us. None of the CD-ROM magazines, made it to the present day, even in radically revamped forms. In a lot of ways, it's because audiences began to treat the kinds of experiences embraced by LAUNCH and Blender as toys, rather than journalism.

This didn't bode well for journalism's advertising model, which relied on in-depth interactions with copy, rather than short, omnivorous clicks. Despite efforts to optimize and target using our personal data, the ad market is arguably still broken to this day—putting too much of an onus on the editorial content to bend to its will rather than sitting next to the editorial copy because it wants to be there.

These CD-ROM magazines at least tried to sell the latter approach, even though we ended up with the former. LAUNCH, with its per-megabyte rates and consistent approach, was more successful than most.

"In some ways, we were too early. What we got most of the attention for was advertising. People had never seen advertising on their computer. We had a lot of investors tell us: ‘No one will ever want to advertise on computer.’ Very well respected, successful venture capitalists," LAUNCH Media founder Dave Goldberg explained in an interview last year.

Goldberg and LAUNCH proved investors wrong, but ultimately, the magazine's ad model looked nothing like how advertising works on the internet today.

The tough part about this story, sort of the challenging thing I have to touch on at this point in the text, is what happened to Dave Goldberg after he spent years innovating in the CD-ROM magazine space. (His idea, by the way, had fans: One such enthusiast has painstakingly gathered every issue at this WordPress site.)

LAUNCH Media almost made a successful pivot away from CD-ROM based magazines by launching one of the first internet radio services. And it had big backers, too: it worked closely with Yahoo at a time when that meant something. Unfortunately, it waded into internet radio at the peak of the Napster era, leading to numerous lawsuits against the company.

Yahoo bought the company essentially to avoid being exposed to lawsuits itself, though the internet giant still had a mess to clean up.

Goldberg's story, for years, was one of success: he worked at Yahoo for six years, got married, had kids, and later became the CEO of SurveyMonkey. He was considered a mentor to many in Silicon Valley.

But last year, things changed dramatically, and in an instant. While on vacation in Mexico last year with his wife, Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, he had an accident while exercising, and died tragically. You may have heard about this—it was a fairly big story when it happened. And it remains a tragic, senseless thing that no amount of me writing will make any sense of. In fact, the only person who has even gotten close is his widow.

"I have learned gratitude. Real gratitude for the things I took for granted before—like life," Sandberg wrote a month after Goldberg's death. "As heartbroken as I am, I look at my children each day and rejoice that they are alive. I appreciate every smile, every hug. I no longer take each day for granted."

This is not the best way to end this issue of Tedium. But sometimes, a trip down the long tail means you have to take some unexpected, dark turns along the way. Sometimes, tragedy touches even the tedious.

:format(jpeg)/2017/08/tedium022316--1-.gif)

/2017/08/tedium022316--1-.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)