Your Secret Amiga

In the '90s, the Prevue Guide—the scrolling spreadsheet of a cable channel that told you what was on the air—kept the Amiga alive way after Commodore died.

Wait, the Commodore Amiga? Why the Amiga?

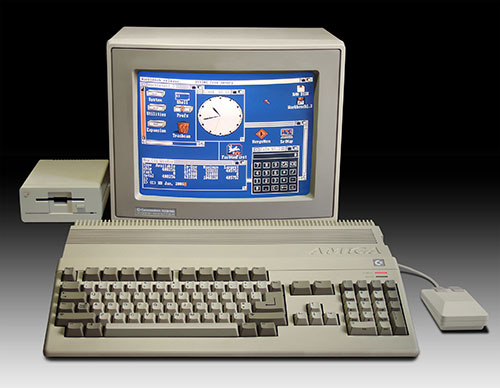

The Commodore Amiga was a much-loved machine that was huge among a cult of users who embraced its impressive video and audio capabilities, which blew away every other platform at the time of its release. When it came to multimedia, it was ahead of both the Apple Macintosh and the IBM PC by nearly a decade, and at the time of its release in 1985, an Amiga 1000 could be had for $1,295, far less money than either of its professional-level competitors. Seeing as "Amiga" is the Spanish word for friend with the feminine ending, it was also friendlier than its office-drone competitors.

(Ars Technica has a long-running series about the Amiga. When you get a chance, dig in.)

For cable providers, this level of capability was a bit of a godsend. Previous offerings on this front were pretty rough—often driven by the Atari 800, a computer that was capable of putting messages onto a television screen, though not without much in the way of pizzazz.

The Atari 800, nonetheless, was the system of choice in 1981 when Time Warner offered access to Compuserve through cable lines as part of its two-way interactive Qube platform. The cable provider offered the computer to customers for free.

The Amiga, however, quickly usurped Atari as the cable industry's computer of choice, especially after the release of NewTek's Video Toaster in 1990. The platform, which used the Amiga in its early years, made it possible to do complex video editing at a small fraction of the cost of other video-editing platforms, making it popular with public-access TV stations.

"We showed the Toaster recently at the National Association of Broadcasters show—this is where the engineers go to buy their stuff—and they came by the booth. They said things like, 'This is unbelievable, this is revolutionary that you can do this in a box for this price,'" Newtek's Paul Montgomery said in a 1990 interview with the PBS show Computer Chronicles.

Video Toaster was so successful that it actually upstaged the Amiga platform as a whole, particularly in the United States. While Commodore shut down in 1994, Newtek is still around.

If you subscribed to cable television in the '90s, you most likely saw Video Toaster in action on any number of public-access channels, particularly on bulletin-board type channels that highlighted what was happening in the local community.

But the most notable use of the Amiga in cable television didn't actually rely on Video Toaster at all. But you're probably more familiar with it—especially if you were trying to find something to watch back in 1997.

40M

Four key features of the Prevue Guide

- The split-screen: Early versions of the platform took up the full screen, but as the technology improved, the top half of the screen was used for a variety of previews—whether for things like HBO, or pay-per-view offerings—as well as infomercial-style advertising, especially for psychics.

- The constant scroll: One thing you'll notice about the Prevue Guide is that you can set your clock based on the way that new shows appear on the scrolling screen.

- The errors. The Amiga was famous for its unusual error messages, particularly "Guru Meditation," which was its equivalent of the Blue Screen of Death. Sometimes, the error would appear while the Prevue Guide was playing, which led to some interesting on-screen displays.

- The music! We can't talk about this thing without mentioning the synth-heavy melodies that would run on this platform at all hours of the day. A YouTube user, PrevueChannelMusic, has gathered many of these Muzak-style tunes for your listening pleasure at any time. Wear headphones.

The iOS developer who built a fan community around hacking the Prevue Guide

Ari Weinstein was just five years old on the day the Prevue Channel became the TV Guide Channel—a point that many fans of the network think the channel lost the plot. Despite that, the channel played a key role in inspiring his still-budding career as a app developer.

Weinstein, 21, is one of the creators of two popular apps, the Apple Design Award-winning iOS automation app Workflow and the Mac app DeskConnect. In January, Forbes added him to their 2016 30 Under 30 class. In a lot of ways, he's just getting started.

Like many programmers, he caught the coding bug while he was still in school. Unlike many programmers, he spent a good chunk of his teen years reverse-engineering old Amigas that ran the Prevue Guide in the '90s. In 2009, he stumbled upon a manual for operating an old Prevue machine, and that led Weinstein down the ultimate rabbit hole.

"I started researching what Prevue was, and it brought back these memories and I just became obsessed with this old TV channel," Weinstein explained in an interview. "I loved the branding of it, for some reason, and the appearance—a lot of stuff about it felt very '90s and brought back good memories. But I also became fascinated with how it worked."

From there, he discovered the history behind the machines—UVSG's role as a vendor to cable companies around the country, what the company did with those machines after they passed their sell-by date (destroyed them, mostly), and how he could get his hands on a few.

"I actually found some of these units by painstakingly following all mentions of it on the Internet and reaching out to people," he noted.

Weinstein didn't just reach out to people, either. He connected them, launching a still-active forum to bring together a surprisingly large community of Prevue Guide enthusiasts, as well as a Wiki to discuss and organize the community's findings around the platform.

He says that the fairly unusual hobby helped him as he moved from working on really old platforms as a teen to really new ones as an adult. Before becoming a Prevue Guide enthusiast, Weinstein built a name for himself in the iOS jailbreaking scene by creating iJailbreak. Between his time reverse-engineering iPhones and reverse-engineering old Amigas owned by cable companies, he's become very adept at using such techniques to figure out the ins and outs of the Mac and iOS operating systems, which DeskConnect and Workflow bend in interesting ways.

"I actually learned a lot on the technical side from reverse engineering the Prevue software, which has helped me a lot in other stuff I've worked on since," Weinstein explained.

$800M

The amount that United Video Satellite Group paid to purchase TV Guide from News Corp. in 1999. The purchase, which came three years after a failed partnership between the two parties, helped spell a key turning point for the Prevue brand and its underlying technology, which helped drive listings and pay-per-view systems around the country. Within months, the Prevue Channel was rebranded to the TV Guide Channel, and soon after the merger, the company moved away from the Amiga platform for good, switching to Windows and an arguably-uglier format. It wasn't long before cable boxes made the listings obsolete, and by 2008, ownership of the channel and magazine were separated once again. By 2014, the TV Guide Channel changed its name to Pop, reflecting a final move away from listings.

Perhaps the best comparison point for this sort of industry-specific acceptance of a somewhat obscure platform is the ATM industry, which somewhat infamously used IBM's also-ran OS/2 operating system nearly two decades after its commercial demise.

But just as digital television forced the hand of the cable industry to improve its technology, the ATM industry will ultimately have to upgrade its machines for a number of reasons, including the growth of both chip cards and mobile payment platforms.

Embedded systems with niche uses probably won't ever go out of style, but if it weren't for guys like Ari Weinstein, we would probably forget about this history entirely, not realizing that there's something really valuable hidden in those scrolling screens.

Our most obscure computing use cases highlight some of the most interesting lessons.

:format(jpeg)/2018/01/qhje80neytjv9zlmdhei.gif)

/2018/01/qhje80neytjv9zlmdhei.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)