When Signal Beats Noise

The concept of "DXing"—basically, trying to capture TV or radio signals from far away—is nearly as old as the antenna. It's a great rabbit hole.

"Under his pillow whisper low, they creep in through his radio, that long-distance howling at the moon."

— A lyric from the 2011 Cowboy Junkies song "Late Night Radio." The song (which you can listen to here) is about how, late at night, you can receive AM radio signals from long distances away. This phenomenon, though somewhat common, is the core of the concept of DXing, and it also highlights the fact that you don't really need specialized equipment to do it—given the right conditions, a regular radio that picks up AM signals is fine, thank you very much. How, you ask? I'll leave this one to the experts: "During nighttime hours, especially during winter, old-fashioned AM radio is able to span long distances due to skywaves bouncing off the ionosphere," a guide from the New Jersey Antique Radio Club explains. "Even a simple radio is capable of hearing stations more than 500 miles away."

(Nite_Owl/Flickr)

The story of DXing starts with amateur radio operators

So what the heck is DXing, anyway? Long story short, it's the idea of catching far-away signals using radio or television equipment, just to see if it can be done—something reflected by the jargony term "DX," which started as telegraph lingo for "distant reception."

The concept of DXing dates way back to the early amateur radio era in the 1920s, and in some ways, helped turn the concept of running a ham radio station into a game.

Experienced amateur radio users, especially those with a lot of equipment, compete to see how far their equipment can reach, and how many stations they can hit from a long distance away.

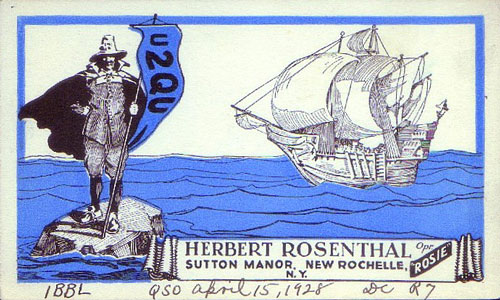

In the pre-internet era, radio operators confirmed their contacts by sending "QSL cards" to operators who asked for them. These cards served a similar process to a stamp on a passport, or perhaps a postcard—they confirmed that a you had made a connection to a certain country or geographic area. (They're also cool as hell. This archive of QSL cards highlights just how far the phenomenon went, along with the sometimes-impressive designs of the cards.)

The 1914 launch of the American Radio Relay League further helped these ham radio operators get more formally organized, and the group eventually helped formalize DXing into a full-fledged yearly contest with rules and standards. In 1935, an ARRL employee named Clinton B. DeSoto set the ground rules of keeping score in the DXing process, figuring out a way for ham radio users to keep score of the number of "countries" they've contacted.

This was not an easy process—because, as it turned out, ham radio "countries" don't work best by treating them as countries with traditional borders, according to DeSoto. Why's that? Well, countries tend to be broken up in complicated ways. For example, if you live in Nebraska, reaching a signal in Alaska is more significant than reaching a signal in Ohio, because of the significant geographical difference.

"It is obviously incorrect to accept either geographical or political divisions alone, as immediately the most glaring inconsistencies appear," DeSoto explained in the article, originally published in QST Magazine. "The only general solution that comes anywhere near to solving the problem seems to be to reduce the definition of 'country' to the smallest common denominator—a single unit in the world's geographical and political proportions."

ARRL has since built on DeSoto's work and now runs a yearly contest called the DXCC Challenge, with prizes for the operators that hit the most "countries." There are even online vendors that sell custom QSL cards, not that they're necessarily needed, because ARRL now offers an equivalent online service that counts toward awards.

Ham radio may have been the starting point for the DXing phenomenon, but there's a lot of other spectrum out there, and that spectrum—be it shortwave, AM, FM, UHF, or VHF—each has its enthusiasts.

Five key things to understand when it comes to DXing

- It used to be easier to pick up DX signals. In the 1940s, the bandwidth allocated to television and FM radio signals ended up on a part of the spectrum where things spread over long distances—allowing, for example, for TV stations from Chicago to show up in Mexico, no satellite necessary. This threatened to crowd out local radio signals, so the FCC eventually changed the frequencies used, so as to prevent interference.

- Some signals are harder than others to pull. The reason why the subject of that Cowboy Junkies song was able to hear all those long-distance radio signals is that the AM waves are particularly attuned to long trips, partly because there's more room to tune. Shortwave, likewise, is easy to pick up from long distances. TV signals and FM signals, on the other hand? Those tend to be at parts of the spectrum that don't generally go outside of the city of origin in normal circumstances.

- Atmospheric conditions can boost reach. As Hack a Day notes, varying differences in the atmosphere allow for signals to jump even further from their point of origin. The most obvious example of this is at night, when tuning conditions become more favorable at long distances due to differences in ionization. But powerful signals, in some cases, bounce back from the ionosphere and can be picked up from distances more than 1,000 miles away.

- Location matters, too. If you want to pick up unusual TV and radio stations from different parts of the country or world, your location matters. If you're on the East Coast, for example, you're more likely to hit Africa with your AM signal, and Asia is easier to hit on the West Coast. Some DXers even encourage traveling for the purpose of picking up exotic signals—though probably not with family, because they'll get in the way of your DX pursuits.

- Specialized equipment helps. A true sign of a serious DXer is that they own a wacky antenna or two designed to help make it easier for them to access certain signals. They also tend to be very finicky about their tuners, which help to pinpoint a signal almost exactly, so as a result, they tend to care about higher-end equipment than the average consumer.

10,496

The number of miles between Williamstown, Australia and London—a trip that, by plane, takes roughly a full day to make. That mile count is also an approximate all-time DXing record. In 1957, onetime silent film director and star George Palmer somehow managed to pull a signal from a BBC channel from his Australian home, confirming the impressive feat by recording images and audio from the channel on his screen. Palmer, whose son grew up to be a politician, inspired other generations of DXers, including fellow Australian Todd Emslie, who pulled off a similar feat in 1981, though in that case he was only able to get the audio.

The TV DXing game is starting to get a lot more advanced

For DXers, television's last hurrah as an analog medium raised some serious questions: How is this going to change the process of DXing? Would pristine digital signals make it harder to find unusual stations? And with so many TVs offering digital channel-scanning functionality, would the heavy tweaking so often needed to bring a channel to life eventually make TV DXing impossible?

Long story short: it's still possible, but the process has evolved. Many of the basic techniques still apply, but the lack of snowy signals that barely come in and all means that the process is more complicated and time-consuming. Eric Bueneman, one blogger and DXer, has embraced the results with digital TV, even if it requires some extra work.

"TV DXing, as far as I've found, hasn't been that much different in the digital age than it was during the analog era. It's just that you need more patience to pull in DX," Bueneman wrote in a 2012 blog post.

One facor helping things is technology. Late last year, the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association, a group of enthusiasts, noted that automation and improved antennas have each played a key role in improving the process of finding TV stations.

"What some TV DXers are doing now is automating their DXing," the website states.

Basically, this is done through a couple of tools, including the high-end HDHomeRun TV tuners, which are to TV tuners what Netflix is to Roku. These tuners can be plugged into a site called Rabbit Ears, which keeps eyeing new listings. The result? Suddenly a time-consuming process of elimination turns into a bot, essentially.

Obvious question: Does that take all the fun out of it?

These days, DXing is pretty much a niche hobby, thanks to the internet. Most people don't have to worry about the hard work of tracking down a spare signal from a far-away TV station somewhere, because that station probably has both a website and a YouTube channel.

But at one point, DXing, while still niche, had entire publications dedicated to it. One such magazine, DX Horizons, ran for a short period in the early 1960s. It was mostly dedicated to shortwave radio, and featured the work of perhaps the nichiest of niche journalists, Ken Boord.

Boord had built a career writing and editing about shortwave radio trends, and earned a reputation for his knowledge on the topic, something highlighted by another publication he worked on, "The World At A Twirl." It was basically a bible of all things shortwave and DXing.

But it was in a column he wrote for kids in which he nailed the appeal of DXing, shockingly. In a 1954 issue of Boy's Life, he had this to say about it: "It's not only fun, but it's easy, too! With practice and patience—under normal circumstances—it's no trick at all to listen to all continents in a single evening—at times within only a few minutes!"

It's a weird, obtuse concept, this whole DXing thing. But for a certain kind of person, it's not hard to see why they might share Boord's excitement.

:format(jpeg)/2018/01/vxduvolmvrjfaeicedqv--1-.gif)

/2018/01/vxduvolmvrjfaeicedqv--1-.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)