Recorded For Quality Assurance

It seems like we've been dealing with frustrating call centers forever. But, as it turns out, customer service via phone is a relatively recent phenomenon.

"All of a sudden he would call mother and have four people he was bringing home for lunch because they’d had a mechanical [delay with the aircraft] and they were on the flight, so he just brought them home for lunch. And mother would say, 'Barbara, run out in the yard and pull us some corn.' And I’d go pull about 36 ears of corn and bring them in, and she’d drop them in the water, and lunch was corn and bread and butter and coffee. And that was what we had to offer, and that’s what the airline passengers got when they were delayed."

— Barbara Woolman Preston, the daughter of Delta Airlines founder C. E. Woolman, discussing how, when mechanical delays arose with the airline's early planes, her father would bring home passengers and feed them lunch—an impressive form of homespun customer service that nobody would associate with a modern airline. Occasionally, Preston said that passengers would be overnighted, and she'd wake up on a cot, so the passenger could sleep in an actual bed. This anecdote highlights something important about customer service: Service with a lot of interaction is highly intensive and rarely scaleable. Hence why telephones and chat boxes are used for most of this stuff these days.

The 10-button Western Electric Model 1500. (via electronixandmore.com)

Five key technologies that made phone-based customer support possible

- Touch-tone dialing: Until 1963, numbers went out in a series of pulses around the rotary dial. But when the Bell System introduced dual-tone multi-frequency, it became the basis of touch-town dialing, which made it possible to communicate through the telephone line without speaking. The Western Electric Model 1500, released in 1964, was the first phone to offer buttons to consumers—though it did not include the hashtag or star symbol. Touch-tones didn't become mainstream until the 1980s, however.

- 1-800 numbers: Invented by AT&T scientist Roy Weber in 1967 as a way to make it easier to route collect calls, the company quickly discovered that it was a great way to market products, with airlines and florists quickly jumping on board. It owned an effective monopoly on the numbers until Ma Bell was broken up in 1984—at which point consumers were making 3 billion toll-free calls a year. In 1986, MCI started offering toll-free numbers, which soon brought the concept into the stratosphere.

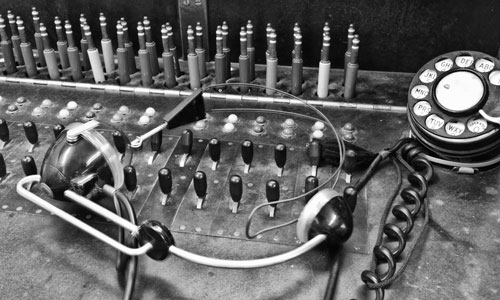

- Private Branch Exchanges (PBX): These devices, dating to the early telephone era but eventually modernized, were essentially mini-switchboards, allowing businesses to route phone calls where needed. They came in two forms: Manual, which required someone to physically route the calls, and automated, which allowed the calls to route themselves. The latter technology was the secret sauce for many call centers.

- Interactive Voice Responses (IVR): This technology is perhaps the most essential for modern customer support calls. First used by bank tellers in the 1970s to verify customer balances, they soon became immensely popular as a way to route customer support calls. These days, this technology is pretty intelligent, able to recognize what someone says, and even in some cases able to analyze a customer's journey in real time.

- Short Message Service (SMS): Invented in 1992 to work with the earliest GSM-based mobile phones, this came about more than two decades after most of the phone-based technology listed here, but in many ways, it's just as important, as it allowed for the quick broadcasting of information and communication with the public. It's the thing that made customer support predictive, rather than reactive. (Hence why GrubHub and Uber are always asking you how your service was.)

(Thinkstock)

How AT&T gave up the opportunity to build the technology behind the call center

Calling up Verizon or Comcast to set up your home service can sometimes feel like a nauseating process of pulling teeth. And shockingly, that service hasn't been with us for a particularly long time.

In fact, the call center as we know it—the large room of company representatives, talking on the phone, selling a product or offering service to existing customers—came nearly 100 years after the invention of the telephone.

There is, admittedly, some debate as to who had the first call center. Clearly, phone companies, who had armies of operators connecting calls, could arguably be considered customer service representatives in the modern sense, though they weren't considered as such at the time.

And doctors, who had to schedule many appointments via phone, were likely early users of 24-hour answering services, which clearly played direct inspiration to today's customer support lines.

One expert on the subject can pin the existence of call centers as far back as 1965. Jonty Pearce, the founder of the online publication Call Centre Helper, says that's when the Birmingham Press and Mail rolled out such a system.

But one use that can and probably should be seen as a line in the sand for modern customer service is Continental Airlines' purchase of a Rockwell Galaxy Automatic Call Distributor (ACD) in 1973. While Pearce calls Rockwell's claim to be the first company to manufacture such a system to be "good marketing baloney," partly because he found another example of it in the wild prior to the Galaxy's release, the purchase nonetheless highlighted the mainstream potential of the technology.

(FWIW, Pearce suggests that ACDs first appeared in the 1950s, and the first major call centers soon after that.)

Rockwell International, now known as Rockwell Automation, was a somewhat unusual firm to take this on—it was known largely for its interest in aerospace and heavy industry, and wasn't previously known for its record in the telephone industry.

But two things happened that gave Rockwell an inside line to building the backbone of the first high-profile call-center. First, the firm acquired Collins Radio Company in 1971, and Continental was already working with Collins on setting up a navigation system, meaning Rockwell had an existing partnership to leverage. But the second factor is perhaps the most curious: AT&T had just rebuffed a request from Continental to build call-center technology itself.

According to a 2007 Los Angeles Times article, AT&T told the airline it would take eight years to build the technology needed to automate the routing of a phone call—a timeframe that suggests, considering AT&T's size, that it was near the bottom of the priority list.

So Continental went with Rockwell, where an engineer named Robert Hirvela did most of the dirty work and received the patent for it. The system worked so well that Continental used it for 23 years, and when they replaced it, they used another Rockwell system.

(That won't happen again, by the way: Neither Continental Airlines nor Rockwell's automated telephone business exist in the form they did in the '90s. After a number of mergers, the call-center business now exists as a firm called Aspect.)

While Pearce emphasizes that Rockwell's ACD wasn't first, he does say that they played an important role in popularizing it—and that the ACD helped change the world.

"The invention of ACD technology made the concept of a call centre possible," Pearce noted in his blog post. "Essentially it replaced the human operator with a far more flexible automated system capable of handling much greater numbers of calls."

"When used properly, an answering machine is the most useful invention out there."

— Peter Theis, the inventor of a number of important telephone-related technologies, including voice mail, discussing in a 1991 Chicago Tribune article how companies have misused his automated technology over the years. Theis generally recommends much thought go into an automated menu. "When programming an automated system, whether it involves speech recognition or not, the focus must be on the communication and not the words that are scripted," he wrote in a 2000 op-ed for Speech Technology magazine.

Despite the fact that call centers seem decidedly low-tech—why call a person when you can shoot along an email?—they have grown increasingly sophisticated with time and are in many ways one of the most elaborate operations in a given business.

As far back as 2005, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of Business wrote a paper about the scientific processes around queueing calls, with the goal of serving customers and lowering headcount.

And AT&T—the company that could barely even be bothered with call centers 45 years ago, but has most assuredly made billions of dollars from their existence—now uses the call-center data to pinpoint problems in its system based on location. The can even detect a customer's mood and respond to that data in real time.

"If a customer is unhappy, we want to do something at that moment in time as opposed to after the conversation is over," AT&T Labs' Mazin Gilbert told CNN Money in 2014.

Though we don't think about it this way, call centers create a lot of data—which is why all those calls may be recorded for quality-assurance purposes.

Some firms are doing next-level stuff with the leverage received from those quality-assurance pledges. One company, Mattersight, is attempting to use analytics to improve customer service experiences by connecting customers with customer service reps that have compatible personalities—an approach that has more in common with online dating than your busted falafel order.

"When you think of big data, there's a ton of data in that spoken conversation. No one is taking that data and trying to operationalize it in a new way," explained Jason Wesbecher, Mattersight's chief marketing officer, in comments to InformationWeek. "Call-recording vendors are out there, but they're not focused on this kind of behavioral science angle."

If there's one industry where the level of innovation rose up like a hockey stick in short order, customer service is it. Not that you'd ever expect that.

:format(jpeg)/2017/06/tedium080216--1-.gif)

/2017/06/tedium080216--1-.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)