The Sound Of Science

Bose Wave stereo systems were legitimately innovative when they launched in the '90s—as was Bose itself. The marketing might make you forget that, though.

“At this moment, I must say that I have never heard a speaker system in my own home which could surpass, or even equal, the Bose 901 for overall 'realism' of sound.”

— Julian Hirsch, a reviewer for the audiophile magazine Stereo Review, offering a notably breathtaking September 1968 review of the Bose 901 speakers, the company’s first popular product. The Hirsch quote (along with "you'll be reluctant to turn it off and go to bed,” a quip from High Fidelity magazine’s Norman Eisenberg) helped solidify both Bose as a company—this quote was frequently used in the company’s ads even decades after the 901 speakers were released—and Hirsch himself (he was to stereos what Lester Bangs was to the music that played on them). The quote is a good reminder that breathless language is not unheard of in the audiophile space—nor in the history of Bose.

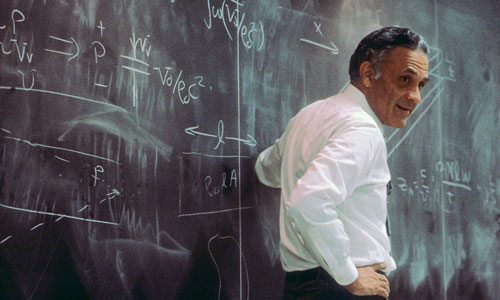

Bose founder and longtime MIT professor Dr. Amar Bose. (Automotive Rhythms/Flickr)

Bose was built on engineering, not aggressive advertising

OK, so we’ve set the stage a little bit—Bose is a giant company that has gained a lot of mileage from oohs and ahhs.

But as a company, Bose gained a heck of a lot more from its purely academic approach. Whether or not you feel the company’s Wave speakers are any good, there’s one thing that can’t be debated: The man whose company still sells those speakers was a brilliant guy whose innovative spirit can’t be defined by a single product, nor his marketing team.

Dr. Amar Bose, a Bengali-American through his father, came to his success though his curious mind. As a 2005 Popular Science profile notes, he was ably taking apart all sorts of devices as a young teenager. He even built his own television. And his smarts proved an effective ticket to a career in academia.

But there was a problem he felt needed to be solved. As a Massachusetts Institute of Technology doctoral student in the late 1950s, he grew frustrated with the poor audio quality of the high-end stereo system he bought himself as a reward.

"I studied the literature and bought the best system based on the specifications. But when I brought it home and plugged it in, it sounded terrible,” he explained to the magazine. “I was disappointed and confused. Why did so much of what I had been taught say it should be good, when my ears said it wasn't?"

That led Bose, who became an MIT professor or engineering, to dive into audio research on how to maximize the sound that could come out of a pair of speakers. Eventually, his research led him to make speakers that worked much the same way as actual music being played in a concert hall did—with the sound waves reverberating off the walls.

This thought process, as immortalized in this 1967 patent, led to the 901 speakers, the devices that helped drive the company’s long-term success. Those are still sold today. That success allowed Dr. Bose, who remained an MIT professor in the midst of his company’s success, to further experiment on all sorts of different projects at Bose, including (most famously) noise-cancelling headphones and (most ambitiously) a car-suspension system built for smooth rides.

The company is privately held, giving it the ability to spend much of its time and profits working on major research projects. One of those projects became the basis for the Wave line of speakers, designed by Dr. Bose with the help of Dr. William Short, a fellow former MIT student. The eureka moment, according to a 1985 Popular Science piece, was when Short had built a primitive form of the company’s “waveguide” technology—an enclosed, serpentine-like plastic chamber that’s designed to help amplify a sound wave and bring out some of its best qualities.

He showed Dr. Bose what he had on Christmas Eve, and Dr. Bose immediately realized he had a very memorable gift sitting in his office.

“After Bill demonstrated the first crude model to me on Christmas Eve in 1981, I ran around the plant grabbing anyone who hadn’t left for the holidays,” Dr. Bose told the magazine at the time. “I wanted everyone to hear the incredible sound coming from this new kind of enclosure.”

That waveguide technology became the basis of the Acoustic Wave Music System, released in 1985, and the smaller Wave AM/FM radio, released in 1993, and dozens of other varieties since.

(Fun fact: The company also produced a massive subwoofer, designed for large group events like movies, that relies on the same technology as the Wave. This article, written by Short, explains how that worked.)

The company priced high out of the gate, predicting a market existed for extremely expensive alarm clock radios—something even its competitors, like Boston Acoustics President Andy Petite, admitted were there.

“There's been a vacancy in the market for a really high-performance stereo/radio,” Petite told the Christian Science Monitor in 1993.

There was. But Bose had to sell a bit of its marketing soul to find it.

14

The number of years that Bose claims it took to research and develop the Wave audio system, according to one of its user manuals. The work on the waveguide technology earned Dr. Bose and Dr. Short numerous awards.

The Bose Wave Music System III, shown with a CD changer. More recent models support Bluetooth. (Handout)

When did the Bose Wave go from engineering miracle to Sharper Image fodder?

Bose’s early success with the 901 speakers and their later variations won them interest from audiophiles, but the company’s decision to later simultaneously target the consumer market and keep their prices high led to continual skepticism from that market. (If you’ve followed Apple with derision over the last 30 years or so, it’s kind of like that.)

Part of that, admittedly, may be partly due to the way the company sold its innovations. For decades, Bose has willingly put its product in the same category of commercial-based sales as stuff on QVC, as the Slap Chop, as Columbia House, and as the Video Professor. What Bose was selling was arguably of higher quality than most of what was selling on Comedy Central at 10 a.m. while Mystery Science Theater 3000 was on the air, but even if it was slumming a little, the strategy was necessary.

The problem is, fancy speakers don’t just market themselves. The public has to be sold on the benefits of those speakers.

The Bose Wave, the successor to the Audio Wave, has been heavily optimized to sell in its current channels—with psychology a heavy factor. For example, when the company struggled to sell Wave systems through magazine ads, the company changed its marketing strategy in multiple ways: It changed the headline on the ad to “hear what you’ve been missing,” then doubled down on the testimonials that worked so well for the 901s.

The example is frequently brought up by Arizona State University marketing professor Robert Cialdini, an expert on persuasion, who says that the approach helped downplay the newness of the device on the market.

“With something new, people are uncertain, and when they are uncertain, they want to avoid losses,” he said in a recent interview with PBS Newshour. “So what the Bose marketers did, they put it at the top of the ad: ‘Something you will lose, something you will miss.’ They put them in the mindset of loss, and people decided to buy this equipment, so they wouldn’t lose the benefits.”

It’s clear by the channels being used that Bose has always wanted the Wave to be a device for the people, rather than the audiophiles. That’s OK. Plebs are allowed to be impressed by a sound system, too, even if they know nothing about proper placement or anything like that.

If there’s a quibble to the strategy, however, it’s that the price and positioning might have caught Bose a bit flat-footed as it became more important for music to be portable.

Fortunately, they had those noise-cancelling headphones.

“Do I consider Bose a rival to even a modest, entry-level high end streaming system? Hardly. But what they lack in sonic excellence they more than make up for in knowing how to sell it. And that's a lesson many high-end companies could learn.”

— Paul Wilson, a columnist for Audiophile Review, offering a critique of the way Bose sells its Wave systems through infomercials. Wilson notes that while the infomercial he watched spent much of its time making the case that the people in the commercial were blown away by the quality of the speakers in the Wave system, some of the time was actually spent on explaining how the speakers worked, including a part where it was explained how sound vibrations go through the Wave system’s waveguide speaker technology by using a candle—an experiment replicated in this YouTube clip.

The weird thing about Bose is that, despite the company’s pedigree, despite these longstanding ties to academia and engineering, they still have all sorts of haters. One clip that stood out to me when I was digging around featured a middle-aged guy who clearly was not impressed by the engineering that was Amar Bose’s life’s work.

“They want a thousand dollars for a clock radio with a bunch of plastic tubes in it to make the sound deeper,” the guy says at the start of the four-minute clip in which he savages the company’s speakers for their reliance on those plastic tubes.

There are reasons to be critical of Bose as a company, not least of which are the firm’s high prices, but describing 14 years of scientific research as a “scam,” as that guy does, is perhaps a little too far.

One random YouTuber’s video isn’t going to ruin Dr. Bose’s legacy.

That legacy, it should be emphasized again, isn’t with infomercials or breathless quotes repeated to death in magazine ads for the speakers he invented.

It’s with MIT, the university whose rigorous graduate program inspired Dr. Bose to reward himself with a stereo, setting the stage for his career in electronics. The school where he taught for 45 years, most of that time while running a name-brand company. And the school that, thanks to an unprecedented gift from Dr. Bose in 2011, is the majority shareholder in the company that bears his name (though has no say in how the company is run).

And it’s with the company he built. Dr. Bose died in 2013. But its devices are still everywhere, no matter how many pairs of Beats Apple tries to sell.

The long, winding trail to the sound that goes through his most famous set of speakers lives on. It gets louder as it goes.

:format(jpeg)/2017/06/tedium122216.gif)

/2017/06/tedium122216.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)