We Nailed It

Fingernail clippers are apparently a relatively recent invention. Did we go through life without an easy way to trim fingernails for thousands of years?

“It is unlucky to cut the finger nails on Friday, Saturday or Sunday. If you cut the on Friday you are playing into the devil’s hand; on Saturday, you are inviting disappointment, and on Sunday, you will have bad luck all week. There are people who suffer all sorts of gloomy forebodings if they absentmindedly trim away a bit of nail on any of these days and who will suffer all the inconvenience of overgrown fingernails sooner than cut them after Thursday.”

— A passage from an article about superstition published in the Boston Globe in 1889 (though credited to the New York Sun), discussing a superstition of the time that suggested people couldn’t cut their fingernails on weekends out of fear that it might lead to back luck. Let’s be honest: This superstition sucks. A much better superstition: The idea that white specks on the fingernails would lead to good fortune.

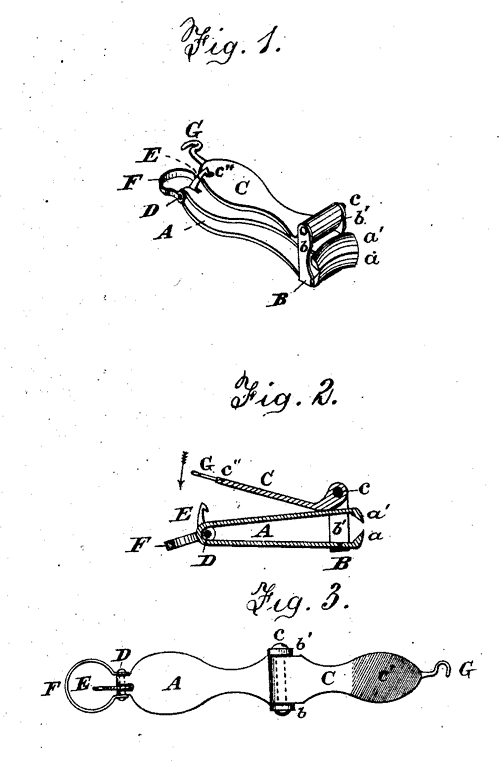

Fingernail clipper patent, Eugene Heim and Oelestin Matz, circa 1881. (U.S. Patent & Trademark Office)

How did people cut fingernails before fingernail clippers? (Warning: Rabbit hole)

Fingernail clippers are a bit of an enigma on the invention front.

Clear answers about the history of trimmed fingernails don’t really show themselves unless you’re willing to do some digging. (Fortunately, that’s what this newsletter is all about.)

It’s not clear who invented the modern fingernail clipper, but patents started to appear for fingernail trimmers around 1875.

The man credited by the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office with the first such trimmer was named Valentine Fogerty, though the design of his device could best be described as a circular nail file rather than a keratin clip. The first design in the USPTO’s files that I could find that could be described as having anything in common with modern designs came from inventors Eugene Heim and Oelestin Matz, who were granted a patent for a clamp-style fingernail clipper in 1881.

A better hint of how fingernails were cut before the days of fingernail trimmers comes from the patent for R.W. Stewart’s finger-nail cutter, which doesn’t work like a modern day clipper. The design, in fact, has more in common with peeling an apple than pressing a clamp.

And if you’ve ever used a paring knife to peel an apple, that’s how fingernails were cut before there was a designated tool for it, whether using an actual knife or small scissors. In fact, based on a look through Google Books for any and all references to the cutting of fingernails, terms like “trim” or “cut” generally weren’t used to describe the process until the 19th century. Before that, we described the process as “paring.”

But that only gets us back two centuries. Where do we go after that?

Well, since we don’t have a firm backing for a lot of this historic stuff, literature is a helpful friend, as it can suggest the ways that things were discussed during certain historic eras.

Going back to the 18th century, for example, Irish dramatist George Farquhar’s 1702 work The Twin Rivals makes a reference to nail-paring in this way.

Here’s a rough translation of the specific passage to something resembling modern English: “… I found another very melancholy paring her Nails by Rosamond's Pond,— and a Couple I got at the Chequer Alehouse in Holboure; the two last came to Town yesterday in a Weft-Country Waggon.”

Going back further, we know a few other things about fingernails—for example, that they emphasized status during China’s Ming Dynasty. Regarding the latter: Basically, you had long nails if you never did hard labor, but often wore your nails short if you did. (That touches on another point about nail length: The more physical labor you do, the more likely your nails are going to be short.)

But where did our interest in well-cared-for fingernails come from in the first place? The ancient Romans, to be specific.

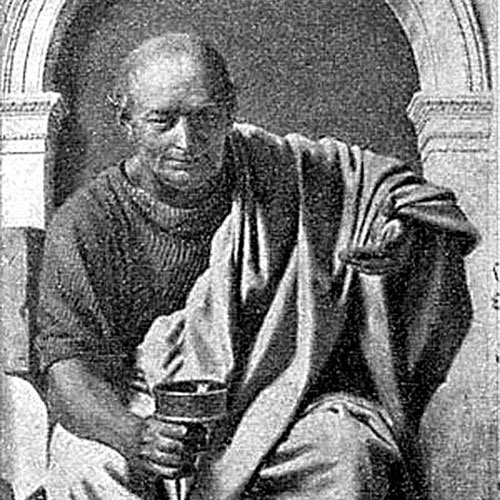

Roman satirist Horace.

Again, the evidence there comes from literature. The satirist Horace repeatedly touched upon fingernails in his works. In the work Satires, dated 35 B.C., Horace came up with the idiom of biting one’s fingernails out of nervousness (or as he put it, with some modernization, “… in the composition of verses, would often have scratched his head, and bit his nails to the quick.”)

But a later work, the first book of Epistles (circa 20 BC), offers up the largest historic hint. In a passage where he introduces an auctioneer, he also makes reference to the process of nail trimming in ancient barber shops. A modern reference from Poetry in Translation:

Philippus the famous lawyer, one both resolute

And energetic, was heading home from work, at two,

And complaining, at his age, about the Carinae

Being so far from the Forum, when he noticed,

A close-shaven man, it’s said, in an empty barber’s

Booth, penknife in hand, quietly cleaning his nails.

Also in Horace's time was a pivotal moment in the history of nail polish. Egyptian pharaoh Cleopatra, who lived between 69 and 30 B.C., was known for using the juice of henna plants to paint her nails in a rust-red color—and due to the social code of the time, she was one of the few to dye her nails red.

Going even further back, there’s a reference to trimming fingernails in the Old Testament (Deuteronomy 21:12), replete with some ancient gender politics. Per the New American Standard translation:

“When you go out to battle against your enemies, and the LORD your God delivers them into your hands and you take them away captive, and see among the captives a beautiful woman, and have a desire for her and would take her as a wife for yourself, then you shall bring her home to your house, and she shall shave her head and trim her nails.”

So based on all that, we’re talking about a written acknowledgement of fingernail-trimming that dates back to, roughly, the eighth century B.C.—a date far before Valentine Fogerty’s existence.

Before that, odds are good that hard labor played a major role in keeping fingernails short.

Or maybe, just maybe, our ancestors bit them down to size.

“Look at all ten nails and pick out the shortest, or that with the smallest amount of ‘white’ at the tip. Use that nail as a reference to ensure all nails are being filed to a uniform length and shape.”

— Deborah Lippmann, a celebrity manicurist, offering tips to GQ on how to trim fingernails to an even length across the board. Lippmann also recommends using an actual emory board on your nail, treating your cuticles right so as to avoid hangnails, and to leave a sliver of “white” at the top of the nail.

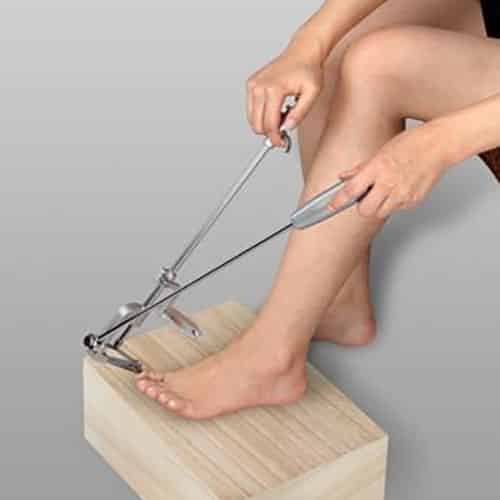

The fairly imposing Antioch Clipper.

Five attempts to make a better nail clipper

- Do your toenail clippers need giant handles so they don’t keep falling out of your hands? If so, the well-reviewed Bezox Precision Toenail Clippers might be your ticket. Maybe they’re overkill, but so are your toenails.

- One of the problems with standard-size fingernail clippers is that one hand is often stronger than the other, meaning that when your non-dominant hand cuts, it’s more likely to slip, making it more likely to bend a nail. A potential solution the the problem comes in the form of a rotary nail clipper, which turns the clamping motion on its side.

- Combining the first two items in a wacky way is the Antioch Clipper, a device introduced in 2011 to make it possible to clip toenails without bending over at the waist—which may be of benefit in some cases, but lends itself to a design that is best described as a combination nail clipper and pair of tongs.

- Nail-clipping luxury: Do you really need the world’s best nail clipper at your disposal, as the Khlip Ultimate Clipper describes itself? Perhaps not, even though it “gives you increased control and leverage as you trim your nails” due to its award-winning design. A Gizmodo review really says it all: “The Klhip Ultimate Nail Clipper Is Ultimately Just Expensive.”

- The Indiegogo route: The Vanrro V1, a futuristic nail clipper, is looking for support on the crowdfunding site, though the term clipper is actually a misnomer—it’s really a nail grinder, kinda like the kind they sell for dogs. But the attempt has only raised $210 so far, and a similar effort shut down with no notice whatsoever last month. Hey, at least the clippers don’t support IFTTT.

Fingernails (and likewise, toenails) aren’t like belly buttons, a minor part of the human body with little to no use in our day to day lives.

Our nails may be minor, but they’re often the last line of defense between us and a lot of pain. They can even serve important functional purposes. Guitarists, for example, often need strong nails to pick strings and strum. But good nails aren’t always easy to pull off.

Fortunately, there’s an expert on the guitar fingernail topic. In 2005, guitarist Rico Stover wrote a book titled The Guitarist’s Guide to Fingernails, in which he describes his frustrations as a guitarist with weak fingernails and his ways of getting around the problem. Soon after, Stover created a website called Ricoguitarnails.com, which features his artificial “Riconails” system—including an “emergency nail kit,” in case your tips aren’t cutting it during your Dave Matthews Cover Band’s big show.

“Anyone can grow good natural nails if they know what to do, when to do it, and why to do it,” he writes on his site.

It’s good to know that there’s someone else besides me who’s thought seriously about fingernails for any significant length of time.

--

Editor's note: An earlier version of this article stated that fingernail clippers aren't allowed on planes. As it turns out, that's not the case. The story has been updated to reflect that. We regret the error.

:format(jpeg)/2017/02/tedium020717.gif)

/2017/02/tedium020717.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)