Delivered To Your Door

The internet made monthly subscription boxes cool, but the roots of this business model can be found in decisions made in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Editor’s note: Thanks to a nice mention by NPR, it’s been a week for the record books here at Tedium in terms of new readers. Welcome newbies; and thanks, everyone else, for not putting us in your “do not read” folder. Something you wanna see us cover? Learn more about what that entails over this way. Oh, and tell your friends, possibly by email!

22.5

The number of trips that a milk bottle tended to hold up for before it broke, according to a 1915 edition of Milk Plant Monthly, which sounds like the greatest magazine of all time. As Wired notes, the milk bottle (invented in 1879) was a key innovation, bringing both sanitation and helping to underline the pitter-patter of regular delivery to homes. It was a downright necessity in the days before regular refrigeration.

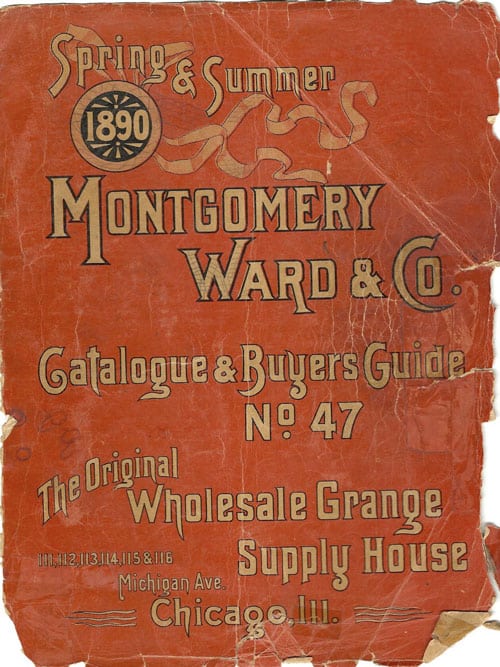

An 1890 Montgomery Ward Catalog.

Five postal innovations that made subscription services possible

- The rail system: Germany got a jump on the rest of the world in delivering parcels in part because it had a strong rail system—enabling the effective delivery of cargo and giving the economy a serious leg up during the 19th century. The global expansion of the rail enabled much of the improvement in the mail system during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- Universal Postal Union: There was a time when it was really difficult to deliver letters from one country to another, due to need for treaties between those countries to allow the delivery of mail. This non-governmental organization, founded in 1874 through the signing of the Treaty of Bern, helped to remove many of the complications that come with delivering mail and created a unified system for mailing letters. Today, UPU falls under the purview of the United Nations, and it’s likely that the UN wouldn’t exist without the existing success of the UPU.

- The parcel post: Before the 1880s, it was uncommon for post offices around the world to accept parcels, something that changed during a monthlong convention on the concept that took place in Paris in 1880—at which the postal services of 19 countries agreed to accept parcels of this nature, according to Global commerce in small boxes: parcel post, 1878–1913, a paper by researcher Léonard Laborie. The United States joined the International Parcel Post in 1887, though it wasn’t available for domestic shipments until 1913.

- Rural free delivery: For a number of years, the U.S. Post Office was not required nor designed to deliver mail to homes in rural areas, which meant that people outside of cities had to pay to get mail delivered or travel long distances to pick up their letters. In the 1890s, that was 65 percent of the U.S. population, so it was a problem. It took years of experimentation and at least one act of Congress to come across a working model—but rural delivery went national in 1902 and helped encourage the creation of roads and other forms of infrastructure.

- Mail-order department stores: Bringing all of fundamental pieces together under a single business model, the mail-order catalog helped exemplify how to make money via the mail and paved the way for the modern postal systems we have now. Montgomery Ward (founded in 1872) and Sears, Roebuck and Co. (founded in 1887) were the two bedrocks of this model.

$100

The amount in starting capital that UPS, originally called the American Messenger Company, began with at the time of its 1907 launch. (With inflation, that’d be $2,430 today.) The service started with just two guys from Seattle, Jim Casey and Claude Ryan, which means that grunge and coffee aren’t the only things that Puget Sound delivered to the world. The firm, which changed its name to United Parcel Service in 1919, first introduced “common carrier” shipping, which offers many of the fundamental elements needed for subscription-box services, after the 1922 acquisition of Russell Peck Company. (It had to buy the company to offer the service, because common-carrier shipping was highly regulated. See, it put UPS in competition with the U.S. Postal Service.)

How the Book of the Month Club made literature accessible to the broader public

The catalogs of Montgomery Ward and Sears were an important proving ground for the value of mail-based commerce.

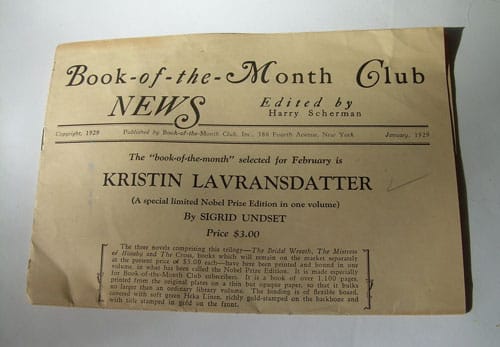

But the connective tissue that took us from commerce to subscription didn’t take hold in the mainstream until a guy named Harry Scherman came along and launched something called the Book of the Month Club. Scherman, a journalist-turned-adman based in New York City, stumbled upon the marketing potential of books in 1916, when publisher Charles Boni showed Scherman a book of Shakespeare, bound in leather. That led him to launch a company with the Boni brothers called the Little Leather Library Corporation, which produced what could best be described as the paperback of its day.

The firm, at first, tried giving away books in other pieces of merchandise as a way to help move products like Whitman’s chocolates. Soon, the firm augmented the approach by selling away a series of books through the mail. However, as Joan Shelley Rubin’s 1992 book The Making of Middlebrow Culture notes, there was one weird problem:

Scherman did have to deal with one disaster, now a comical part of Book-of-the-Month Club lore: as leather prices rose, the publisher switched to synthetic bindings which, it turned out, smelled bad in hot weather. Despite that setback, however, by 1920 the Little Leather Library had marketed over twenty-five million volumes, many of them by mail.

This experience proved informative for Scherman, who combined the Little Leather Library concept with two ideas: The fact that people outside of large cities didn’t have access to high-quality books, and that, to keep the business model strong, mail-order books needed a subscription model. That led him to the Book of the Month Club.

A Book of the Month Club newsletter, circa 1929. (Joanna Bourne/Flickr)

The model, formulated in 1926, proved hugely important for the publishing industry. (It also spawned an immediate copycat, the Literary Guild.)

Scherman’s strategy—with the help of a committee that selected the books—brought a curatorial eye to the publishing industry, something that immediately proved controversial among booksellers, who understandably saw the clubs as dangerous to their bottom line. A duo of New York Times stories say it all: On May 16, 1929, attendees of the American Booksellers Association’s annual meeting were simply mixed on the concept. In the next day’s paper, however, the association had passed a resolution criticizing the clubs.

The model, an obvious inspiration for later services like Columbia House and the Video Professor, straddled this line of praise and controversy for decades, though the model got a bit sleepy in the age of the internet. In 2014, it even briefly stopped operation.

But in 2015, however, it received a refresh, with a big social media presence and an editorial director, Maris Kreitman, best known as the author of the Tumblr Slaughterhouse 90210.

The model isn’t about cultural necessity anymore, but about consistent value among its bookworm audience.

“So much time is spent staring at various electronic screens these days,” said Kreizman told the Los Angeles Times. “People are looking to make some room for pauses in their life.”

In other words, it’s become more niche, like all the subscription box services it later inspired.

“Partly the disparity is due to bans on direct shipments by retailers. While boutique wineries usually are happy to ship you a case, direct shipments by brewers and distillers are much less common, which means someone searching for a rare gin or unusual beer generally has to rely on retailers. But even if producers were willing to send you beer or liquor, your state might not let them.”

— Jacob Sullum, a senior editor for Reason, discussing the annoying legal complexities around shipping alcohol in certain states in a 2013 article. This complexity has made it so that it’s much harder to find a beer-of-the-month club versus a wine-of-the-month club, despite the two beverages being treated otherwise roughly the same under the law at retail. The wine industry is working to improve the legal state of affairs, however—according to a map from The Wine Institute, just six states bar the shipping of wine these days, compared to 10 at the time of Sullum's article. To this day, the U.S. Postal Service can’t legally ship alcohol through the mail, though legislative attempts to reverse that come up from time to time.

Going back to my list above, it’s worth noting that the thing that’s killing the U.S. Postal Service—the internet—may be enabling the of-the-month subscription service model to thrive.

It’s a cool way for niche products, like big and tall clothing for guys, to work around the inherent weaknesses of traditional retail, which often fail to properly nurture such niches. And it's also leading to experiments that can best be described as performance art in mail form.

But ultimately, these products are still physical. And these kinds of businesses come with tons of complications, due to all the logistics. To give you an idea, the online platform CrateJoy, which offers tools for entrepreneurs to create their own subscription-based services, can feel terribly complex, despite the fact that the service actually makes things easy. Thing is, you can’t get around the fact that the logistics of physical products are really hard to get around.

We haven’t reached the push-button simplicity of The Jetsons yet.

--

So, to end this, I wanted to mention a weird experiment we’re trying—an idea I'm calling “curated shopping.”

For those who sign up (you don’t have to, I ain’t mad either way), once a month I’ll buy you something weird, either of up to $10 in value, or up to $25, depending on the tier you sign up for on our Patreon page ($25 or $40). The idea is that you support Tedium and I send you weird stuff related to my recent issues—say, an obscure type of screw, or a book about ranch dressing. Simple as that. No fancy box; it'll be delivered the way God intended: Through a standard online retailer.

I have no idea if this is going to work (though I am a guy who’s good at finding weird things on Amazon) but it’ll be fun to try.

Anyway, enough with the spiel. See ya next time.

:format(jpeg)/2017/02/tedium021617.gif)

/2017/02/tedium021617.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)