Frickin' Laser Beams

The tale of Science Faction, a company that brought massive laser light shows to venues around the world. They blew a lot of minds along the way.

"His mind raced as the dimensions of the breakthrough continued to reveal themselves. He could achieve, in an instant, temperatures hotter than the sun. He could cut holes in steel, cause chemical reactions, perhaps trigger nuclear reactions.”

— Author Nick Taylor, writing of Gordon Gould’s revelation of how a laser should work, according to his book Laser: The Inventor, the Nobel Laureate, and the Thirty-Year Patent War. Gould, a physicist, wrote of the concepts of building a laser in 1957, getting his forms notarized in a candy shop. However, he didn’t attempt to patent them until 1959, at which point Charles Townes and Arthur Schawlow had already filed patents of their own. (Gould and Townes, who was working on the same problem, knew one another, and Townes had advised him on filing a patent.) This state of affairs led to a lengthy legal battle that was eventually settled in 1988, with Gould receiving credit for helping to invent the laser and generating a whole lot of debate in the process.

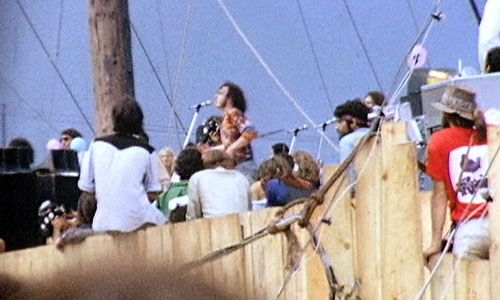

Joe Cocker performing at Woodstock in 1969. Richard Sandhaus played an important role in making this performance happen. (Wikimedia Commons)

The teenage concert promoter who had a vision for what rock and roll could look like

In the late ‘60s, Richard Sandhaus was a college student on the East Coast who had turned his desire to put on “the best junior prom ever” into a successful career as a concert promoter.

He had fingerprints on all sorts of big bands of the era, bringing in acts like The Animals, The Young Rascals, The Who, The Doors, and Cream for all sorts of local audiences. At an age when many folks hadn’t even held a job that paid above minimum wage, Sandhaus was paying his tuition by putting some of the biggest bands in the world in front of massive audiences of his peers. And despite his age, he was a savvy negotiator.

"It just takes time working with managers and agents to tell when you have a good deal and when you're getting taken," a 21-year-old Sandhaus noted in a 1970 Hartford Courant interview.

This, of course, brought him to Woodstock, where he found himself after being tasked with getting a British singer and his band to the field in one piece. That Brit was Joe Cocker, who would have his American breakout moment in that Upstate New York field.

There were probably a lot of people having revelations in the middle of Max Yasgur’s 600-acre dairy farm, but Sandhaus’ revelation—discovered far from the stage, where he had mostly been located—would prove particularly important to his future career and the evolution of the outdoor concert.

“I went out into the house, as it were, out into the field, way back, and I watched a little bit from something like a mile away,” Sandhaus recalled in an interview. “And it was—at that point, sound reinforcement systems had just gotten to the point where you could deliver pretty good quality sound to people quite far away in an outdoor venue. But the stage was still this teeny thing, it was like ants on stage performing. And I thought, ‘God, it’d be really great to have some large-scale visual version of rock’n’roll.’”

That moment turned out to be a fundamental one for Sandhaus, who eventually tired of promoting concerts and was soon looking for a career change.

For awhile, he attempted experiments with large-scale video projection, and also tried to use the then-budding satellite technology at the time to beam concerts to local colleges—but neither approach worked; the technology just wasn’t up to snuff. But there was another type of visual that was starting to come into its own: The laser beam.

In the midst of his research, Sandhaus went to the 1970 World’s Fair in Osaka, Japan, where he got an up-close look at an effort by Hitachi to put the world’s largest laser video projector on display. He got a demo of the device, which significantly beat anything the U.S. was doing at the time. There was a problem, though.

“After kind of a lot of negotiation, I got to see the projector, which turned out to be a laboratory that was 20 feet by 15 feet, completely jam-packed with equipment,” he said.

He realized it would be awhile before such technology was ready—but it did plant the seed that lasers could be the solution to his problem of giving rock concerts a visual language.

By the time he turned 26, he decided to switch gears—devoting himself full-time to laser light shows.

28

The number of years Laserium was active at Los Angeles’ Griffith Park Observatory, where it became a full-fledged phenomenon upon its 1973 debut, eventually showing up in planetariums around the country. (Currently, Laserium generally hosts shows—soundtracked by classic albums, of course—at its Van Nuys, California studio.) Sandhaus admits being inspired by the work of Laserium and its creator, Ivan Dryer, but emphasizes he ended up going in a different direction with it—by focusing on putting those lasers in front of huge audiences.

A mobile laser light show, produced by a Science Faction truck in 1988. The company spent upwards of $1 million on these laser-emitting vehicles. (Dick Sandhaus)

What it was like running a company that produced massive outdoor laser light shows

By the time a 1979 New York Times article about laser light technology had hit newsprint, Richard Sandhaus had fully reinvented his career. Starting Science Faction in the prior year, Sandhaus had turned what was a personal interest of his into a groundbreaking business.

Sandhaus at the time was pitching the idea of purchasing lasers for the home, which the firm was selling at the time for thousands of dollars a pop.

(The article, side note, also features former Kiss lead guitarist Ace Frehley discussing buying a laser for his home. Choice quote: “When I saw it, I had to have it. When you turn it on, all of a sudden this circle of light starts to float near the ceiling. It's relaxing; you can really go away and almost meditate on it.”)

It’s in that piece where Sandhaus describes the combination of lasers with music in a fairly intriguing way—as “the first worthwhile color organ.”

Sandhaus’ company was putting the idea of synchronizing music and visuals into action at large concert venues and disco halls during the era, but it turned out the company’s true legacy was by putting on elaborate visual displays of its own, with Sandhaus being the major creative force.

A big driver of this was the evolution of lasers from analog to digital technology. This allowed for more creative types of treatments that could communicate sophisticated stories to large audiences using lasers.

“Every kind of moment, every scene in every show would be—at least, the stuff that I did—was really about kind of the transformation of images in space and over time,” Sandhaus explained. “And so, the big wow factor for the audience was how this became that.”

Technically, making all this work was quite the challenge. Effectively, the company was trying to build complex graphics using machines that are very primitive by today’s standards.

Larry Alice, an engineer and artist who was hired to work with Science Faction in 1982, notes that the company purchased some of the earliest IBM PCs to help put together the complex calculations needed to display the complex vector graphics to the audience. And before that, Sandhaus says, the company would often pull together machines using parts garnered from Radio Shack.

“When I started they were still building computers from scratch, literally,” Alice explained.

A close-up of Science Faction's Mondial du Laser entry. (Dick Sandhaus)

Over the years, Science Faction worked on a wide array of projects, including multiple world expos and the 1998 Winter Olympics. At one point, the company represented the U.S. in Mondial du Laser, an international laser light competition that took place in Montreal in 1992. (They won gold, of course, with an elaborate conceptual piece about the pre-history of communication.)

A scene from Science Faction's Lasercast at the World Trade Center. (via Dick Sandhaus)

The company also put on a spate of laser light shows from the observation deck of the South Tower of the World Trade Center in 1991.

Alice remembers the challenges the high-up setting created, both practical (he noted the high heat left him terribly sunburned) and technical.

“All the microwave transmitters in the city were up there. They drove the computers crazy,” he recalled, adding that he ended up having to cover the computers in aluminum and gold foil to get them to work properly.

Science Faction’s work proved popular and marketable—the company even garnered sponsorship from AT&T for a national tour over a multi-year period.

By the late ’90s, however, Sandhaus says he ended up transitioning away from the laser-light industry—feeling that the work was starting to get stale—and moved toward web design.

His laser light work continued for a while—most notably at New York’s Grand Central Station and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, but eventually, it stopped entirely.

He was ready for something else.

These days, Sandhaus is well along with his most recent reinvention—as a tech-friendly fitness guru.

He helped design the iFit technology, an early example of a virtual personal trainer, for ICON Health and Fitness, and these days, he runs a subscription-based online platform called BetterCheaperSlower, that’s targeted toward keeping older adults active. (He also has an app called Treadmill Trails, which allows treadmill walkers to get a spring in their step in a slightly more creative setting than their living room.)

He hasn’t done a laser show in roughly a decade, and in many ways the business of live event visuals has changed significantly. Those giant screens that weren’t ready in the 1970s? They’re ready now, and they’re everywhere.

And while lasers are still a part of it, Sandhaus worries that the approaches to laser light shows have regressed some since he was in the game.

“I think it’s because the cool people making cool technology are into very different technologies,” Sandhaus says.

Lasers may be a bit old hat these days when it comes to large-scale visual entertainment, but there was a time when they were on the bleeding edge.

And a spark of inspiration at Woodstock was quite likely the reason for that.

--

A quick thanks to Larry Alice, who brought this amazing tale to my attention. I greatly appreciate it.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece misstated Sandhaus' role at Woodstock. We regret the error.

:format(jpeg)/2017/03/tedium031617.gif)

/2017/03/tedium031617.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)