Pictures For Everyone

The reason we’re so crazy about photos in the smartphone era is in no small part because of early innovations that brought photo processing to the masses.

Editor’s Note: Hey all! My pal Andrew Egan, last seen writing on Tedium about the art of the DVD commentary, has a few thoughts on photo-developing technologies—and how they took pictures mainstream. It’s a lot to reflect on. Check it out!

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

“Unexpectedly the photographing booth at the Woodlawn country fair… has become a detective agency. A picture take of George Wiseman, former clerk at the Colonial Hotel, is expected to lead to the fugitive’s arrest.”

— A quote from an October 1902 story in The Inter Ocean, a Chicago newspaper, detailing the capture of fugitive that resulted from being recognized from a photo booth picture. Strange crime stories were staples of media—both then and today—but this story resulted from the relative novelty of the then-new technology.

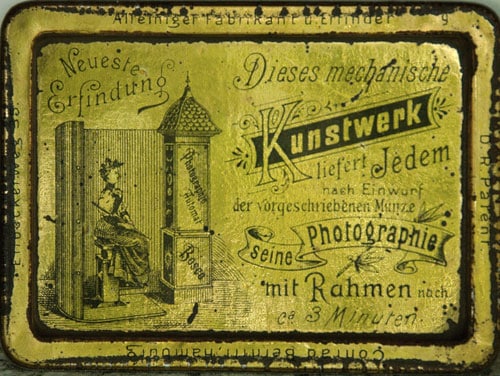

A sample of the backside of a Bosco Automat print. (Wikimedia Commons)

The early days of the photo booth, a key way photos went mainstream

From the beginning, photographs have entranced inventors, artists, and entrepreneurs with fabulous possibilities. Unfortunately, the technology often lagged behind their ambitions.

The first fully functioning photo booth premiered in Hamburg, Germany at the First International Exposition of Amateur Photography in 1890. Known as the Bosco Automat, it took 3 minutes to develop a ferrotype and was ultimately unsuccessful.

There were plenty of attempts before the relative success of the Bosco. T.E. Enjalbert patented another ferrotype producing photo booth that debuted at the Paris World’s Fair in 1889. Like the later Bosco, Enjalbert’s machine produced simple photographs on tin that quickly faded.

Rolf F. Nohr, a professor at the Braunschweig University of Art in Germany, explained that while the format of the photo booth was mostly set by these devices, they had some distinct differences from the booth of the modern day.

“These early machines are stand-alone arrangements that consist of a photography column and a chair for ‘poseying the subject’,” he wrote in an essay in the 2013 book (Dis)Orienting Media and Narrative Mazes. “However, almost all of these early techniques are just ‘semi-automatic’ techniques that require a ‘machinist’ that takes care of the coin-automatism, carries out the regulation of chemistry, explains the function of the machine to the customer, or just takes reorders,”

More than three decades later, a feasible commercial photo booth finally debuted to the public. Invented by a Serbian immigrant to the U.S. named Anatol Josepho, the photo booth exploded in popularity. In the coming years, trips to carnivals and boardwalks were incomplete without a strip of somewhat grainy black and white photographs. Artists like Andy Warhol would embrace the technology to offer new perspectives on culture. And in the process, Anatol Josepho became a millionaire.

The Photomaton, as it was originally known, took years to create as Anatol tinkered with chemical formulas in hopes of finding a faster developing process while maintaining picture quality. Though running a successful photography studio in Shanghai, China, Anatol decided to relocate to America to secure financial backers to build his machine. After raising $11,000 (approximately $150,000 in 2017), Anatol built his first Photomaton and opened for business in Midtown Manhattan in 1925. Lines quickly wrapped around the block with as many as 7,500 people a day paying a quarter for a strip of eight photographs. (We did the math for you: that’s $1,875 a day in 1925 or more than $25,000 a day in 2016.) Anatol’s Photomaton became known as “Broadway’s Greatest Quarter Snatcher” and he started dating a silent film star named Ganna.

But Anatol’s run at the American dream wasn’t over just yet. In March 1927, The New York Times ran the headline, “Slot Photo Device Brings $1,000,000 to Young Inventor”, on their front page. An investment group led by Henry Morgenthau, a former ambassador to Turkey and founder of the American Red Cross, offered Anatol a buyout and royalties for his patent. He accepted. The next year, he sold the European rights.

“I don’t remember the things that started me on the invention,” Josepho told the Times in 1927. “The idea gradually grew on me that it would be a great thing commercially to invent a coin-in-the-slot machine which would automatically photograph the sitter, develop the photographs, dry them and deliver them.”

He later added, “I shall certainly dedicate much of my life and this newly acquired wealth to helping my brother inventors achieve the same success.”

Anatol Josepho died in 1980 in a La Jolla, California nursing home.

2,269

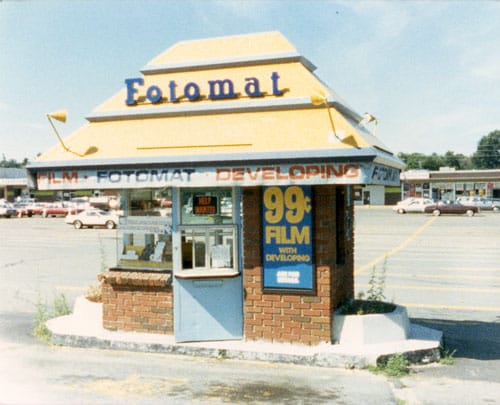

The number of Fotomat locations in 1975. At its peak, the chain had nearly 4,000 locations, but they had dwindled to around 800 or so by 1990, according to the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. They were already on the decline before digital cameras were even a thing—in part because of competition. In 1981 for example, Technicolor, a company better known for its movie film technology, launched a competitor to Fotomat.

A typical Fotomat booth. (Wikimedia Commons)

The tiny huts that pushed photography well into the mainstream

For all their appeal and profit, photo booths have one obvious drawback: they are stationary. For more efficient developing, photo booths also generally printed in black and white. But amateur photographers began desiring full color pictures that took considerably longer to develop. By the 1960s, tech had not yet caught up with consumer desires, so one entrepreneur stepped in with a plan.

Fotomat opened its first location in 1965 in San Diego. The company’s plan to provide convenient, relatively quick photo development proved to be a huge success. Fotomat kiosks, distinctive for their golden pyramid roofs, soon popped up in suburbs across America. Overnight picture processing quickly grabbed investor’s attention too. In 1971, Fotomat was listed on the New York Stock Exchange for public investment. By 1983, the company had an annual revenue of $236.7 million but the pressure was already mounting.

The company’s business model struggled to keep up with its own growth.

“The biggest single factor was our own ineptitude,” Fotomat CEO Richard Irwin told The New York Times in 1981.

Technology that slowly inched forward for decades suddenly began making great strides.

650

The number of 4x6 prints that modern “minilabs” can produce per hour. A minilab is capable of processing film, then printing or processing the results. Most modern minilabs can also convert digital files to high quality prints.

A one-hour photo location at a Rite Aid. (Thomas Hawk/Flickr)

From overnight to instant, photo processing started developing quickly

The retail photo finishing industry had become big business by the end of the 1980s, reaching $4.5 billion in annual revenue. Almost one-third of business was dominated by technology that was widely available a decade before. One-hour photo development, made possible by photographic “minilabs,” gave people high quality prints with unprecedented speed. Of course, early entrants into the field charged almost twice as much as their overnight competitors.

“We live in an instant-gratification society,” said one owner of an Atlanta-area one-hour photo store. “We want things now. The one-hour, on-site lab can provide that.”

The high initial cost of buying a minilab limited their proliferation to large urban centers until pharmacies and supermarkets introduced them as loss leaders for prescriptions and groceries. Minilabs proved to be excellent additions to established brick-and-mortar operations but started the gradual decline of standalone retail picture processing. Fotomat bounced between sellers after its founder Preston Scott sold his stake in the company. The company tried to fight back, even starting one of the first VHS rental schemes.

Eventually, Fotomat succumbed to the drumbeat of digital innovation, but managed to hang on until 2009.

Paul Simon released “Kodachrome” in 1973. His ode to photography captures a unique love, on that inspired Kubrick, Simon, and countless others.

The chorus, of course, speaks to a gentle joy that the technology offers:

“Kodachrome / They give us those nice bright colors / They give us the greens of summers / Makes you think all the world’s a sunny day / I got a Nikon camera / I love to take a photograph/ So mama don’t take my Kodachrome away”

But modern distinction between film and digital has long been lost. With the right printing and editing software, a digital picture can be made to look like it came from high quality film. Think about it this way: If you were to let a physical photo sit around, out in the open, for 12 years, odds are that it might show signs of wear and tear. If you were to look at a photo from 2005 on Flickr—like, say, this one—the photo isn’t going to look like it’s aged a day. For all we know, it could have been taken yesterday. Carbon dating on that picture simply won’t work.

A purist’s desire for physical warmth ignores the reasons motivating development in photo technology: to more conveniently capture the moments of our lives.

Andrew Egan is writer and editor of Crimes In Progress. His work has appeared in Forbes Magazine, ABC News, Atlas Obscura, Tedium, and more. He is a graduate of the University of Texas at Austin. His novel, Nothing Too Original, is available now for Kindle and paperback. You can visit his website at CrimesInProgress.com.

:format(jpeg)/2017/06/tedium060217.gif)

/2017/06/tedium060217.gif)

/uploads/andrew_egan.jpg)