Life In Four Colors

Somehow CGA graphics, the IBM PC’s first take on color, haven’t completely faded into history. But those four colors inspire a whole lot of nostalgia.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

four

The number of colors that CGA displays could put on the screen at once in its low-resolution 320x200 mode, out of a selection of just 16 colors. This would be fine, if not for the fact that you couldn’t really choose the colors that showed up on the screen. Generally, CGA had two modes: One that displayed red, green, yellow and black; and another that, more questionably, displayed cyan, magenta, white, and black. The limited color palette didn’t leave a lot of wiggle room—the colors could be shifted only by intensity, rather than developer preference.

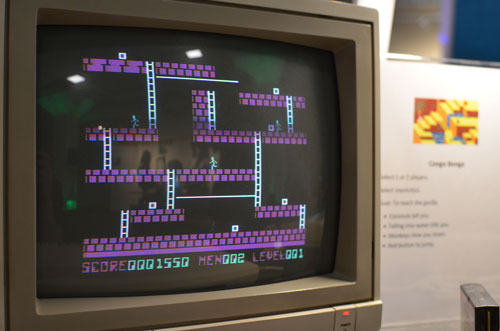

Nothing like cyan and magenta graphics, I tell you what. (Matthew Ratzloff/Flickr)

Why did IBM limit its CGA graphics capabilities so severely? Blame technical and business challenges

The graphics of the original IBM PC might be remembered in some ways as the machine’s greatest achilles heel, a sincerely questionable approach that stood in contrast to the genuinely good graphics that could be found with video games of the era.

Case in point: Arcades were full of video games that were clearly more capable and visually appealing than the color shades that IBM used in its CGA color adapter in 1981, the same year Galaga and Donkey Kong were unleashed upon the world. These games had resolutions slightly lower than the CGA’s low-resolution mode, but they were otherwise comparable.

Those games didn’t have garish cyan and magenta tones as their defining characteristic. Why did the IBM PC?

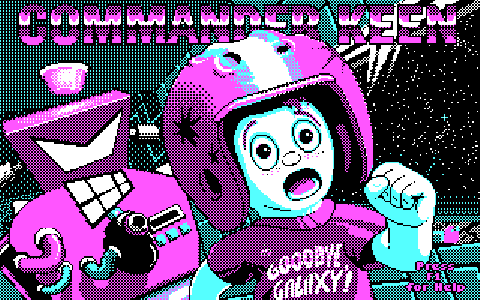

Commander Keen is a perfect example of a CGA-supporting game.

Certainly, there’s a technical case for the issue. For one thing, those arcade games were completely built around those games, meaning there was hardware support for the on-screen imagery. And IBM had to worry about how much this technology would actually cost, no matter where it ended up. Now add to all that the fragility of the technology itself and you have a concoction of CGA trouble.

In the 1994 book From Pixels to Animation: An Introduction to Graphics Programming, an instructional guide to graphics programming techniques, author James Alan Farrell puts the problem less at IBM’s feet and more at the limitations of the era:

Because it was the first it is crude, hard to use, and the colors it produces are not very good. This is not because monitor technology in the early 1980s was so bad. This is because the price of RAM was quite high and things were done to save as much RAM as possible. This means that there was not enough to hold the data needed to make a good looking display or to make it easier to program.

One of the issues as well involved the limitations of how the RGBI (red, green blue, intensity) monitors interacted with CGA cards. RGBI monitors, which were also used with other computing platforms of the era, could actually display many more colors than in CGA’s standard 320x200 mode—as seen in its 16-color text mode—but CGA’s RAM limitations meant the adapter couldn’t actually access those colors in normal use. Beyond black, the monitors could display a standard three colors in CGA’s 320x200 mode, but offered a layer of “intensity” to help create brighter variations on the colors. Problem was, these two types of colors were not available at the same time—creating a frustrating limitation.

But another factor here may have been cultural. To put it simply, IBM had a reputation to uphold with business users, and there was little argument for putting a lot of extra energy into things like color and sound—despite the fact that machines considered to be home computers, like the Apple II, were actually somewhat more powerful graphically.

This was reflected in some of the business decisions Big Blue made on the launch of the IBM PC. The company released two separate graphic cards for the machine—one monochrome, one color—and put clear weaknesses in each. The Monochrome Display Adapter, beyond not supporting color, had solid text-rendering capabilities and a parallel port for printers. The Color Graphics Adapter, meanwhile, lacked the parallel port and didn’t display text as nicely, as its maximum resolution (640x200) was lower than that of the monochrome card (720x350).

As PC Magazine’s Will Fastie put it in June 1983, “the desire to the compatible with all types of display led IBM into this corner, and it’s not clear how it will get out.”

Ultimately, it was the marketplace that gave IBM a nudge—firms like Hercules developed highly functional graphics cards that filled in the gaps created by this approach. Compaq even combined the monochrome and color monitor cards onto a single card.

“The marketplace decided, as it often does, that IBM’s product introductions were not sufficient,” PC Magazine’s Stewart Alsop recalled in 1986. “IBM’s monochrome display adapter couldn’t display graphical images, and IBM’s color card couldn’t combine color with 80-column text.”

IBM eventually improved this state of affairs by releasing its Enhanced Graphics Adapter (EGA), but high initial prices limited that standard’s uptake, ensuring CGA stuck around a little bit longer—and also making sure that nearly a decade of games supported the graphics card after the fact.

Considering the depressing, compromise-filled history around the technology, you’d think CGA is a technology that’s destined for the dust bin of history—but you’d be wrong.

“OK, so CGA probably doesn’t look like it’s very good for playing video games. But if you’re thinking that, it’s probably because you’ve only ever seen it connected to an RGBI monitor.”

— YouTuber David Murray, better known by his fans as “The 8-Bit Guy,” explaining in a clip last year a notable quirk with CGA graphics: While most users are familiar with CGA graphics as displayed by an RGBI (red, green, blue, intensity) monitor, the results were often different when using composite monitors—most notably, television sets. This was because of a quirk with the way composite screens display pixels—basically, the colors would mush together on the screen, making it possible for the screen to display up to 16 colors at once. Problem was, composite screens simply weren’t very good at displaying text, making the monitors basically useless for businesses.

A screenshot of “Guns and Stallions,” a CGA Jam entrant.

Four colors, no limits: How CGA Jam is culling lots of life out of CGA’s limited palette

At one point when questioning Davit Masia about CGA Jam, the game-development competition he put on to encourage game development using the famously limited palette of old CGA computers, I inevitably used the world “ugly” to describe the graphics—and more specifically, their reputation among computer users.

“Come on! Ugly why?” he stated.

I found the Spanish indie game developer’s reaction to that term fascinating, but perhaps I should have been ready for it. Masia, who has been active in doing art for game projects for nearly two decades (most recently under his Kronbits monicker), has recently found success putting on a series of competitions that take advantage of the very kind of limitations that CGA thrives upon.

Masia’s CGA Jam, which recently completed its submission period and is in the voting stage, is an example of a Game Jam, a developer competition that’s akin to a hackathon, except with the end goal of creating a playable demo. While the jam format has existed for a few years at this point, with the help of platforms like Itch.io, Masia has particularly been successful at organizing such jams: On top of CGA Jam, he drew a ton of interest with his earlier 1 Bit Jam—which featured a total of two colors, black and white.

“I think color restrictions are good for creativity and help to improve art skills—or simply for fun, to see what you can do with such limitations,” he noted.

With 136 entries produced in a two-week period for CGA Jam—based on four game themes, including “history repeats,” “always faster,” “gravity,” and “wild west—a lot of designers clearly agree.

The entries may have graphics based on vintage technology, but some of the games are clearly inspired by the modern day. For example, Corgis and Cowpokes features the internet’s favorite dog as a playable character, while Zling is based on the much more modern mobile game Sling Kong.

(One thing you won’t need to play the games, however, is a vintage machine. Many of the games are browser playable, and others work on Windows, MacOS, or Linux.)

Overall, Masia says the competition—which is accepting votes on entries through June 24—drew a lot of creative entries, especially within the Wild West theme. Others used neat graphical tricks to get the most out of the limited color palette. Masia is still digging through himself, but CGA Jam is living up to its potential so far.

“I’m overall very happy with the entries,” he added.

“The minimum target system I set for the project was an original 4.77mHz 8088 class machine with only 128k of RAM. In today’s age of ‘just throw more hardware at it,’ cutting the code down to the bone was a refreshing change.”

— Jason Knight, the developer of the Pac-Man clone Paku Paku, describing his process toward programming the game, which notably takes advantage of an undocumented 160x100 graphics mode, which makes available the full 16-color CGA palette. Knight isn’t the first to use this screen mode—as Nerdly Pleasures notes, early developers like Windmill Software got a lot of mileage out of its early ’80s arcade clones by using this resolution, while others took advantage of the 16 colors made available in CGA’s 80x25 text mode. Technically, that’s what the 160x100 does, too—It’s a hack of the 80x25 text mode that shrinks the available number of lines available for each character, making it a pseudo-graphics mode that gets the advantage of the extra colors. Paku Paku is quite well-done, even without keeping its graphics tricks in mind.

CGA Jam is of course a fascinating attempt to breathe some life into probably the most derided color palette in computing history, but it’s clearly not built around the hardware of that era. (Some limitations are just too much, apparently.)

But creative folks always find a way. In 2006, a guy named Jim Leonard produced a demo named 8088 Corruption, which used the IBM PC Model 5150 to produce full-motion video in text mode. It’s a petty fun watch, but arguably not as fun as 8088 Domination, a 2014 demo from Leonard that recreates many of the same tricks in full graphics mode, and also shows off what the high-resolution black-and-white mode can do with just silhouettes.

But perhaps the most famous CGA-based demo is a little ditty called 8088 MPH, released in 2015 by a team of people that brought up the color count from an anemic 4 or 16 all the way up to 1024. (This complicated explanation notes the alchemy needed for that trick. There’s also a slightly less-complicated explanation, too.)

Maybe it seems wasteful—taking a graphics technology with limited modern-day appeal and doing yeoman’s work to see how far it can stretch. But in an era when we take things like color and resolution for granted, it’s almost refreshing.

And there are times in the modern day when the graphics get so sophisticated and slick that you need the refresh.

Sometimes, less is more.

--

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify the limitations of CGA cards in regards to both color modes and what the monitors of the era could display.

:format(jpeg)/2017/06/tedium061517.gif)

/2017/06/tedium061517.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)