When Time Became Money

The story of the calculagraph—a vintage device that helped pool halls, workplaces, and telephone operators track time—and the phrase that helped inspire it.

Editor’s note: Hey guys! Ernie here, handing the floor over once again to Andrew Egan, who last showed up on Tedium to tell us all about photo processing. Today, he’s talking about the value of time.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

10k

The number of copies of the Poor Richard’s Almanack sold at the height of its popularity in the 18th century, according to the 19th-century book Lives of the Presidents of the United States. The publication formed the basis of Franklin’s wealth while offering weather forecasts, puzzles, and basic fare offered by Reader’s Digest two centuries later. Despite the prominence of the Almanack, one of his most famous maxims never appeared in it.

The 1815 painting Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky, which shows off Ben Franklin at his most awesome. (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

How’d we get the phrase "Time is Money," anyway?

As the writer and publisher of the Poor Richard’s Almanack, Ben Franklin contributed countless idioms to the American dialect of English. "A penny saved is a penny earned", “early to bed, early to rise”, and “word to the wise” are just some of the wisdom that Franklin espoused in his colonial best-seller. But one of the founding father’s best known phrases never appeared in the publication.

The phrase "time is money," rather, was coined by Benjamin Franklin in his “Advice to Young Persons Intended for Trade.” The exact quote: “Remember that time is money. — He that can earn ten shillings a day at his labour, and goes abroad, or sits idle one half of that day, though he spends but sixpence during his diversion or idleness, ought not to reckon that the only expence; he has really spent, or rather thrown away, five shillings besides.”

"Time is money" is a phrase that, like many of Franklin’s aphorisms, has its origins in similar phrases written decades and centuries prior.

A passage from the 1993 book Wise Words and Wives' Tales: The Origins, Meanings and Time-Honored Wisdom of Proverbs and Folk Sayings Olde and New details the history behind the phrase:

While this familiar maxim may seem like an invention of our hectic and impersonal modern society, it actually comes to us from the ancient Greeks. Antiphon, an orator who wrote speeches for defendants in court cases, recorded the earliest known version of the saying in 'Maxim' (c. 430 BC) as 'The most costly outlay is time.' Centuries later, the notion of time's value appeared in English as 'Tyme is precious,' which was included in Sir Thomas Wilson's 'A Discourse Upon Vsurye' and John Fletcher's 'The Chances.' A century after Fletcher, Benjamin Franklin rendered the exact working of the current version in 'Advice to a Young Tradesman' , and the saying afterward came into wide use.

"Wide use" might be a bit of an overstatement. In the years following Franklin’s death, the phrase commonly appeared in English spelling books in reprints of his original Tradesman article. Curiously, between 1829 and 1837, appearances of “time is money” in print nearly quadrupled. This seems to be attributed to the rise of the American railroad network. Trade publications at the time invoked the phrase to tout the benefits of faster transportation and the infrastructure investments to make railroads possible.

"‘Time is money’, says Dr. Franklin, and if it be allowed that Distance is Time, surely the means of overcoming the one are second in importance only to those which facilitate the improvement of the other!" wrote Railway Locomotives and Cars, Volume 1 in 1832.

Franklin’s saying was largely understood as an abstract. The direct correlation between minutes in the day and money made or spent was still awaiting mechanical advances that were still decades away.

"If time is money, don’t you think it is worthwhile to be accurate?"

— An advertising slogan for the calculagraph, published in a 1906 edition of the American Telephone Journal. What the heck is a calculagraph? Simply, it’s a device that accurately tracks elapsed time, removing the possibility of clerical error.

It's certainly better than a guess. (The Magazine of Business, Volume 8/via Google Books)

The guy who invented the calculagraph, which literally turned time into money

Like many watchmakers in the 1880s, Henry Abbott had a problem. Watchmaking requires extensive knowledge and skill, but the business itself is often rooted more in fashion than science. The success of a watchmaking business has often been based on skill and the ability to ride trends and consumer demands.

In March 1888, yet another trend (changing key-wound watches to stem-wound versions) was on its way out, and Abbott’s workshop in lower Manhattan, then the center of America’s watchmaking industry, was quickly losing work. Though he didn’t specifically invoke the wisdom of Ben Franklin, Abbott had stumbled upon the same idea, and turned it into a machine he called the calculagraph.

"This instrument grew out of the idea that elapsed time per se has value; that in some industries it is bought and sold as a commodity," Abbott told Telephony: The Journal of the Telephone Industry in 1943. By then, Abbott was in his nineties and waxing philosophical about his life and career.

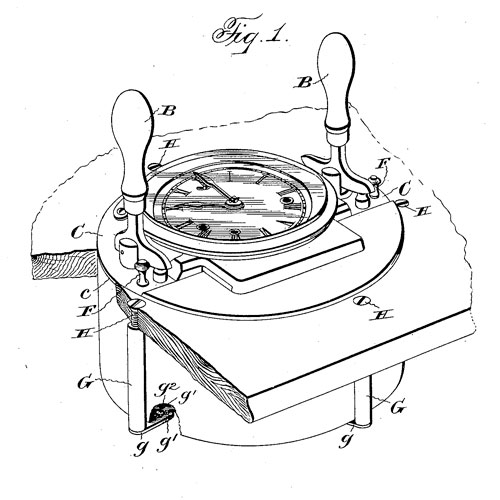

A patent illustration of a calculagraph. (Google Patents)

The creation of the calculagraph was based on the idea that time is money, but it also relied on another, perhaps equally common, idea: People are stupid. Abbott was more artful in his description.

"[T]he operation of subtraction of one time-of-day from another time-of-day should be performed by a machine rather than with the brain and a pencil," Abbott added.

The watchmaker sensed he had a blockbuster product on his hands, but creating a new market proved difficult. As Abbott would write some years later, "We found selling the calculagraph far more difficult than its invention."

Pool halls also proved to be reliable customers. The calculagraph helped end surly customer bickering about how much time was spent playing. Abbott also built one for a dentist who wanted to accurately bill patients based on time. (One interesting side note: Abbott said that dentists in the early 20th century earned $15 an hour, or $375 per hour in 2017.)

It makes no clerical errors. (The Magazine of Business, Volume 8/via Google Books)

Eventually, Abbott and The Calculagraph Company found reliable customers in among phone companies, especially for timing long-distance phone calls as usage along lines increased.

An 1895 Los Angeles Times article explained why this machine was particularly useful for phone companies.

In exchanges doing extra-territorial business or in which toll rate is charged instead of a flat subscription rate, each subscriber's call must be recorded. This requires time, and even the slight unavoidable delay may give rise to complaints. In the long-distance telephone service, which Is exclusively on the toll system, every possible means for shortening the time between the ring-up of the calling subscriber and the beginning of conversation with his correspondent has been applied, and the introduction of the calculagraph, which performs a variety of functions heretofore requiring time and manual labor on the part of the operator, has resulted In a marked gain in the efficiency of the service.

Unfortunately, getting orders from phone companies took much longer than Abbott expected. According to the article in Telephony, "it took 35 years to get the distribution that Mr. Abbott expected to attain in five years."

At the end of his life, Abbott wasn’t too keen on his impact. In the Telephony article, Abbott, then 93, downplayed his own importance.

"Any time you get to thinking you’re indispensable, son, go out and draw a jug of water at the pump," he said. “Then bring it in and set it on the kitchen table. Then stick your finger in it. Now pull your finger out. See the hole your finger left in the water? That’s the kind of hole you’d leave if you left.”

"Why are we wasting time figuring out how much time we’re wasting? People are spending far more time creating these elaborate systems than it would have taken just to do the task. You’re constantly on your app refiguring, recalculating, recategorizing."

— This lament on modern time management apps and technology, offered up by productivity expert Laura Stack [in a 2015 Fast Company article]((https://www.fastcompany.com/3041278/the-perils-of-time-tracking), reflects much the same problem Abbott encountered more than a century before. As Telephony noted, "Many a telephone man was stonily convinced his own pet system of timing calls was 100 per cent right—even one who racked with stop watches in front of each operator for the purpose." People are bad at managing time, regardless of the wisdom or technology available to them.

Time can enhance or diminish reputations. Time helped build a fortune for Abbott, but like many innovators of America’s industrial revolution, he ultimately faded into obscurity. Franklin achieved lasting fame for a simple pamphlet he published in the 1700s. Or maybe it was being one of the founders of America. Who knows?

For a saying to take hold, it needs to have some context. People have long understood that wasted time costs money but even Franklin relayed his wisdom using days length. For minutes and seconds to mean real money, an accurate method of keeping time needed to develop.

Until clocks became ubiquitous, calendars could track a day or two of work. In modern times, we’re never further than a few feet from an accurate clock (though setting the right time for them was once a challenge), leading to a visceral understanding that "time is money."

While Franklin may have coined the phrase, it was Henry Abbott that made the truism into reality—for better or worse.

Andrew Egan is writer and editor of Crimes In Progress. His work has appeared in Forbes Magazine, ABC News, Atlas Obscura, Tedium, and more. He is a graduate of the University of Texas at Austin. His novel, Nothing Too Original, is available now for Kindle and paperback. You can visit his website at CrimesInProgress.com.

:format(jpeg)/2017/07/tedium070617.gif)

/2017/07/tedium070617.gif)

/uploads/andrew_egan.jpg)