The Back of the Napkin

From soft dough to paper, the world’s definition of a napkin has evolved significantly over the past couple thousand years. (It’s currently evolving again.)

1887

The year that souvenir table napkins took off in the Western world, after the British firm John Dickinson Ltd., which had acquired decorated napkins from Japan, had overprinted logos and other marketing-related information on top of the napkins, turning them into souvenirs. According to The Encyclopedia of Ephemera, it was a bit of a strange mix: “Most of the border designs were fairly dedicated, but the overprinting was commonly primitive,” author Maurice Rickards explained. In case you wanna get a close-up look at some decorative napkins from the era, Princeton has a few.

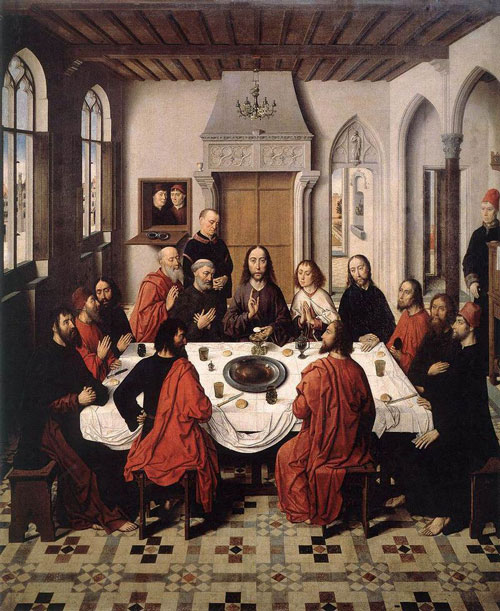

A panel from “Triptych of the Last Supper,” a Dieric Bouts painting from the 15th century. Note the use of the tablecloth as a giant communal napkin. (Wikimedia Commons)

The slow evolution of our napkin usage habits

As it turned out, the first napkin was edible.

We can thank the Spartans in Ancient Greece for that. See, in those days, they ate everything by hand, and that led to the common use of a soft dough to clean off the fingers, a food object called apomagdalie. They didn’t have any other options nearby, so it was necessary.

“Table cloths and napkins were unknown; the place of the latter was taken by soft dough, on which the fingers were rubbed,” explains The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks, a book by 19th-century archaeologist Hugo Blümner. “At large banquets, sometimes towels and water for washing the hands were handed round between the courses, and this was always done at the end of a meal. The practice of using the fingers for eating made this indispensable.”

This, of course, was only a starting point. Eventually (particularly in the Middle Ages), the pieces of dough became pieces of bread. The Romans introduced two kinds of cloth for napkin-related purposes—the sudarium, a “sweat cloth” of sorts for the face, and the mappa, a large cloth for eating while reclining.

Paper, which is said to originate from China, found one of its earliest uses as a napkin, according to researchers Joseph Needham and Tsien Tsuen-Hsuin, who wrote in the book Science and Civilisation in China Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology; Part 1, Paper and Printing that napkins folded into squares were used inside of baskets that held tea cups.

Of course, the Middle Ages had a way of recalibrating things some. For a while in Europe, there weren’t really napkins at all; people wiped their hands and faces with bread, their shirts, whatever else was around. Napkins eventually came back in a big way and added an air of formality to many settings—particularly as tablecloths. These cloths eventually made it to less formal settings, too.

“The introduction of the fork, however, caused eating to become so cleanly a process, especially in contrast to the recent past, that the napkin no longer held its ground as an article of use, but became merely an ornament and a thing of ceremony. It was found that, with a little care, one could retire from the table without the necessity for cleansing the hands.”

— Albert Aylmer, writing in an 1887 edition of Good Housekeeping about the role that the fork played in setting the role of the napkin. Forks were slow to gain acceptance in Europe during their early history, not being used in many countries until the 17th and 18th centuries. (As Aylmer so eloquently put it, Mary, Queen of Scots “probably lost her head on the block before she ever had an opportunity of looking upon a fork.”) But when they did, it led the napkin to lose its footing as a formal table setting. It wouldn’t be the first time the napkin has taken a hit to its reputation—and it wouldn’t be its last, either.

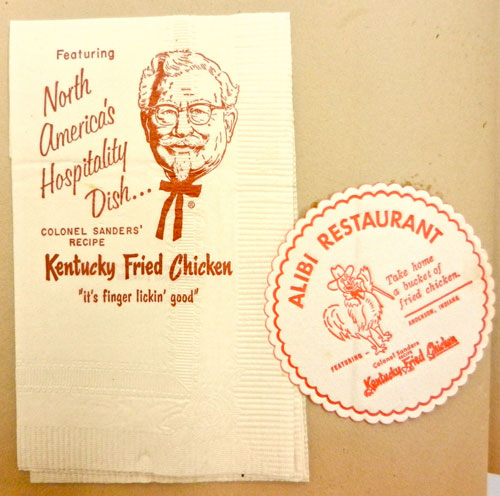

A KFC napkin from 1959. (Ross Griff/Flickr)

How paper napkins, the scourge of formal dining, came into play

As for paper napkins, those didn’t start coming on string until the late 19th century, thanks to the help of the Japanese market. In a syndicated column, Helen Thompson of Brooklyn Magazine noted some initial skepticism around paper napkins:

“Paper napkins! Who ever heard of such nonsense! What good are they?” were among the many exclamations uttered by good housewives when they first learned that wiper napkins were being sold for table use. They pictured to themselves squares of thin, white paper that would break at the first attempt to put them to use, and sighed over the frivolity of the Japanese for bothering to make such articles.

Now, however since their value has become known, every picnic party must be well supplied with these little squares of Japanese art. Hotels and boarding-houses have begun to use them, greatly to the delight of their guests, and it will not be long before restaurants, steamboats and even private families will have them in use.

And while paper napkins were seen as something of a faux pas in social settings, the reputation eventually faded around the 1950s as paper napkins improved and convenience won out. A major turning point came in 1948, when Emily Post gave paper napkins a partial seal of approval. When asked whether it was better to reuse a cloth napkin or use a fresh paper one, she went with paper.

“It’s far better form to use paper napkins than linen napkins that were used at breakfast,” she said at the time.

Soon enough, we stopped caring about being cordial and started getting real.

A paper recycling facility. (MCPA Photos/Flickr)

Five reasons why it’s probably not a good idea to recycle a napkin or a paper towel

- They’re near the end of their life cycle already. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, paper can generally be recycled five to seven times before it runs out of uses. And napkins, paper towels, and other kinds of waste paper tend to be near the end of that cycle, basically formulated from a slurry of water and old paper. (This video, showing the process of creating toilet paper, offers up a pretty good idea of what that recycling process looks like.) If you’re using a napkin that’s been recycled, odds are much of the material in that napkin has gone through the recycling process multiple times, with fibers too short to be reused again. In a way, a recycled napkin is already a reusable success story.

- Um, germs. Not to gross you out, but a 2011 study from the American Journal of Infection Control notes that unused paper towels tend to already have germs baked in—and at a rate of 100 to 1,000 times more in recycled paper towels than virgin pulp paper. (However, it should be noted that there were no reports of consumers getting sick from using these recycled sheets of paper, and the researchers said that the real issue in this case was the use of recycled napkins in hospital settings, where patients have lower immunities.) You think your used tissue is helping that state of affairs?

- Contamination: You know how you’re not supposed to recycle pizza boxes? (Wait, you didn’t know?) The reason for that comes down to the fact that the box is naturally contaminated with the oils from the food, which is difficult to sort out in the recycling process. Likewise, used napkins often fit into this category. Stanford University’s recycling program says that oils from food or other objects can be difficult to remove from paper—pizza boxes in particular. “Since the paper is mixed with water in a large churner, the oil eventually separates from the paper fibers,” the university states. “The oil does not dissolve in the water, instead it mixes in with the paper. The eventually result is new paper will oil splotches. The mill we take our paper to asks us specifically to not include pizza boxes.”

- It hurts the value of other recyclables: Your dirty napkins and paper towels, mixed with other contaminants, can cause problems for municipal recyclers, who get paid more for their recycled materials when they’re “clean,” and don’t have much in the way of contaminants. “By providing clean recyclables, you can actually save your city (and ultimately, taxpayers) money,” notes Kiera Butler in a Mother Jones article.

- Composting is a better alternative: There are a whole bunch of things you probably shouldn’t compost (pizza boxes are on that list, sorry), but napkins and paper towels are OK, as long as they aren’t greasy. In fact, one major napkin-maker, SCA, certified its Tork brand of napkins as compostable under the Biodegradable Products Initiative in 2011.

Do napkins have a paper towel problem?

Earlier this month, the paper napkin brand Vanity Fair, owned by the paper conglomerate Georgia Pacific, attempted to make a hip napkin commercial, if you’d believe it.

The commercial shows a guy pull a pice of food out of his son’s bib, then use a napkin, at which point a waiter shows up and says in his snootiest voice, “how lovely.”

I know, not exactly high art, but according to AdWeek, this is apparently a strategy that the Koch Industries-affiliated napkin brand feels it has to make.

“We’re trying to make Vanity Fair Napkins, as well as the broader napkins category, more relevant to today’s consumer,” explained Lloyd Lorenzsonn, Georgia Pacific’s brand building and innovation leader of napkins (what a title!), in comments to the magazine. “These are universal situations we can all relate to and [the spots] serve the job of reintroducing the napkins within that context.”

And there’s a reason for all that. You know how, last year, there was a report that said millennials don’t eat cereal? We do; it inspired a piece on our end of things.

As it turns out, the same research firm that came up with the data points about cereal and millennials also had a less-noticed-but-still-notable finding on napkins about a month later. The problem, notes Mintel, is that younger people see paper towels as being just as good.

According to stats reported by The Washington Post last year, 86 percent of consumers bought paper towels, while just 56 percent bought napkins.

Now, if you’re me, you might be asking yourself, “What’s the difference? It all goes the same place anyway, and Georgia-Pacific owns friggin’ Brawny anyway!”

The secret here is that it’s one less thing that the average household is buying, which means that it’s one fewer item Georgia Pacific is selling to consumers. The company, per the Post story, noted that around four in 10 people buy napkins on a regular basis, down from six in 10 fifteen years ago. They lost a couple people in the translation, particularly younger people.

“Millennials eat more on the go, they eat more meals away from home and less around a table.” noted Dan Nirenberg, Georgia Pacific’s marketing director for napkins, in comments to the Post. (Of course, they run into lots of napkins on the go.)

Does it make us horrible people if we give up on buying napkins because paper towels do basically the same thing and it’s cheaper to buy one papery item rather than two?

I would argue probably not. But I would also argue that it does highlight the fact that our habits in regards to napkins, which started with edible scraps and eventually moved to disposable pieces of heavily recycled paper, are fairly malleable.

It wouldn’t surprise me if, even considering Georgia-Pacific’s massive size and foothold on the market, the public moved away from paper napkins or towels altogether at some point.

If you look in aggregate, the world has constantly been changing its napkin habits forever. How much do we lose if the paper isn’t pre-folded?

Nothing says that we have to use napkins.

:format(jpeg)/2017/08/tedium080817.gif)

/2017/08/tedium080817.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)