Editor’s note: Last week, Daily Tedium took a week off, in large part because I felt icky about writing anything related to the news cycle in the wake of the tragic Las Vegas shooting. We’re slowly getting back into things today.

As noted by the fact I linked to seven different places in the prior paragraph, it’s been written about at length, by people way smarter than me.

But not every angle has been covered to death. I’d like to focus on one element of the Columbus story that I think has been somewhat ignored by the public: We don’t actually know what he looks like.

He died before anyone anyone created an official portrait of him, and while many folks have attempted to paint him over the years, those paintings—perhaps most famously, this 1519 Sebastiano del Piombo portrait—were all created years after his 1506 passing.

“Much about Columbus is shrouded in mystery,” historian Robert Hume wrote in his 1992 book Christopher Columbus and the European Discovery of America. “There are more than eighty portraits of the man, none of them painted during his lifetime. Apart from the aquiline nose, each portrait is different. Some show a long face, others an oval face, still others a beard.”

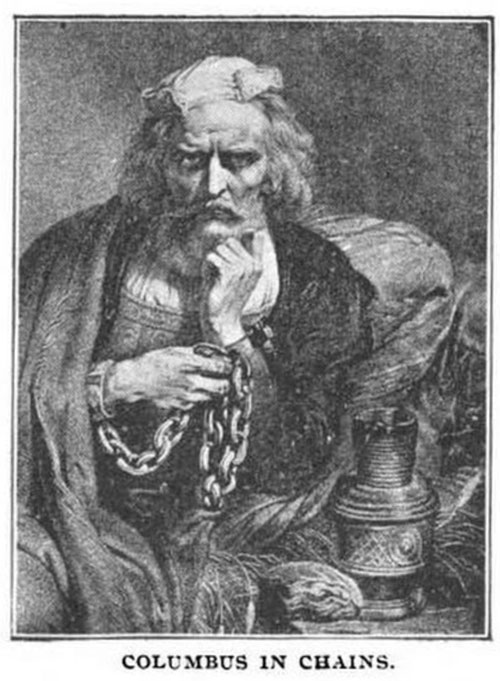

Some portraits portray Columbus as sullen or thin, others as full-figured with a full head of curly black hair. Sometimes, he’s shown with a beard; other times, he’s clean-shaven. But we have little physical evidence of whatever look the controversial explorer preferred.

A few interpretations of Columbus. Yes, these are all of the same guy.

In 1893, historian William Eleroy Curtis wrote a book on Columbus’ many visual interpretations, noting that the result was akin to paintings of the Madonna or ancient religious saints. (Among those saints is another holiday icon, Saint Nicholas, who looks nothing like the modern-day Santa Claus.) Unlike those figures, however, Columbus lived in a period when we often documented our important people in visual form, which makes the situation unusual.

We do, of course, have text descriptions of what Columbus looked like, including this one from his son, Fernando, as quoted by Curtis:

The admiral was a well-made man, of a height above the medium, with a long face, and cheek-bones somewhat prominent; neither too fat nor too lean. He had an aquiline nose, light-colored eyes, and a ruddy complexion. In his youth he had been fair, and his hair was of a light color, but after he was thirty years old it tuned white. In eating and drinking he was an example of sobriety, as well as simple and modest about his person.

This description and others, while including some details, have a vague sense to them, where you’d never be able to create the real thing without a picture.

The alleged contemporary drawing of Columbus, as published in the Scientific American in 1893.

There was a rumor at the time of the release of Curtis’ book, recalled here by Scientific American, that the famed Italian painter Titian was responsible for a drawing of Columbus produced during his life—they were just barely contemporaries, so it was possible—but the publication’s Ricki Rusting expressed skepticism that it was legit, for understandable reasons. (Curtis’ book features a different work, credited to Raphael Mengs, as a recreation of a Titian work that he says is “unlike any other representation of him.” We may never know.)

It’s fascinating to consider—one of the world’s most well-known figureheads, someone who cities and countries have been named for, and statues have been produced of, may as well be a blank face with an aquiline nose for all we know.

All we know, really, is that he represents something that understandably makes a lot of folks mad. Unlike most other icons of his time, he's more myth than man—despite the man threatening the myth.

Above: The Sebastiano del Piombo painting of Columbus that perhaps has defined his "appearance" in the public consciousness more than any other.

:format(jpeg)/2017/10/1009_columbus.jpg)

/2017/10/1009_columbus.jpg)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)