It’s New To You

The story of FuncoLand, the retailer that made the used video game market a thing—and how GameStop, which bought Funco, sort of bastardized that mission.

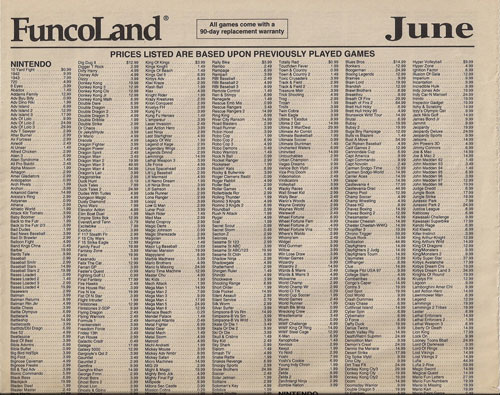

29¢

The price that Stadium Events, the infamously expensive 1987 Bandai NES game, sold for in a 1999 flyer for FuncoLand that was faithfully republished on Imgur in 2014. (The game’s apparent value only showed itself after the fact.) Other notable rare NES games that could be had for fairly cheap then (at least if you could find them in store): Little Samson was selling for $6.99, Panic Restaurant for $3.99, and Power Blade 2 for $1.99. Each of these games, per Price Charting, sell for hundreds or even thousands of dollars on eBay and other places today.

The FuncoLand website, circa 1998. (via Internet Archive)

The story of FuncoLand is the story of a guy who pulled a success story out of a corporate bankruptcy

David Pomije, the Minnesota-based founder of Funco, didn’t have things easy when he launched his budding used video game empire.

In fact, he was running at a deficit to get the thing off the ground. He was already a failed business owner twice over when he he came up with the idea for the company while declaring bankruptcy from his previous failure, a firm called Protectronics.

That company, which sold equipment for Commodore 64 machines, lost its way after the Commodore market dried up, and that meant he was stuck liquidating the company’s assets—which meant that his dad’s retirement savings went down the tubes in the endeavor.

But in the midst of all this liquidating of stuff, Pomije had an idea involving one of the things that Protectronics was trying to auction off—a collection of 1,100 NES games, at a time when NES games were the hottest thing on the block. Per a 1998 Fortune article, he realized that if he rented out the games himself, he could probably do a pretty solid business.

Pomije got some help from his dad, who cosigned the $8,000 loan that helped him buy the games out of the auction—at a relatively inexpensive $7.27 a pop. Soon, Funco was in business.

Pomije, having been burned by investing too aggressively using other people’s money, focused on trying to build his empire solely using profits he earned from his library of games. He initially rented out space in local video stores, which worked at first and bought him a little runway, and soon he had the idea of buying and selling used video games, taking advantage of the fact that gamers always want something new to play.

He didn’t have a store at first, so he used the pages of Electronic Gaming Monthly, one of the most iconic magazines of its era. He was not the first person to do this; there were a few other companies that pledged to buy games in the early issues of EGM. (On the other hand, EGM was certainly no Computer Shopper.) But Funco’s ads, with their detailed lists of game prices and very favorable payouts—after buying back titles for $10 or more, Pomije’s company would add a markup, but not an unreasonable one—proved particularly effective.

“I felt tingles up the back of my spine. I knew if I could do this a thousandfold, I had a business,” he recalled in Fortune of finding games and checks waiting for him at his mailbox for the first time.

The challenge for Funco—which makes their story interesting—was that the company wasn’t just building itself, but it was effectively inventing a proper market for something that had usually been handled through classified ads or via person-to-person trades in the past. And that meant the firm faced challenges in properly pricing games based on market demand.

A FuncoLand price chart. (via estarland/Imgur)

Games weren’t considered collectibles at the time, and as a result, there was no set guide for how much a game was supposed to cost, like there was for, say, baseball cards. Funco had to invent a model, and if they got the model wrong, they would suddenly be stuck with a lot of extra games nobody wants, or missing a hit game that everyone’s looking for.

According to a 1990 profile of the company in the Minneapolis Star Tribune, this model was initially done using whiteboards, by hand.

“It’s taken a year to find the equilibrium point for each individual title,” he noted, adding that unexpected surges in popularity—caused by things like the title character from Kid Icarus showing up in a Saturday-morning cartoon—could throw everything off.

Soon enough, Funco had both a blossoming mail-order business and a few retail spots, with the locations called FuncoLand.

In one of the training videos for FuncoLand that’s since been posted to YouTube, Pomije told a very passionate story about a product the company sold that most people wouldn’t think to take all that seriously—the cleaning kits for games.

In the video, he explained how his son wanted to play a Robocop game that he brought home, only for the game not to work when he tried to play it. “Later the next day, we discovered the reason why: it simply just needed a good cleaning.”

Pomije and his team would tell gamers that over the phone in an effort to get them to buy a game maintenance system—and to hear the Funco owner tell it, the pitch was really successful.

“I’d get calls and thank-yous, not because we sold something for somebody, but we took our time and we offered them something that would protect their video game system, and more importantly, from those disappointing moments in life,” Pomije stated in the video.

Laugh all you want, but those cotton swabs and that rubbing alcohol helped save David Pomije’s career.

1991

The first year that the magazine Game Informer first published. Initially a magazine targeted at in-store customers of FuncoLand (and published in six-page circular form), the magazine quickly became hugely popular in its own right, with more than 100,000 subscribers by 1994. Nowadays, it’s one of the most popular magazines in the country with an epic 6.3 million subscribers as of 2017, making it the fifth-highest-circulated magazine in the U.S. To put this number in perspective: That’s a larger circulation than Time and Sports Illustrated COMBINED.

FuncoLand’s fast-growing retail trajectory ended in a really depressing way

When Fortune wrote about FuncoLand and Pomije in 1998, it was not because the company was struggling. Not by any means, in fact. It was in second place on the magazine’s list of 100 fastest growing companies—which makes sense, considering that the company had evolved from a mail-order-only company to a retail juggernaut with hundreds of locations in just a few years.

And it did so despite the fact that FuncoLand’s logo looks like it directly inspired Google’s original logo. So branding wasn’t exactly a strong spot for the company. But it had earned a trusted reputation among gamers, especially those looking to offload an old game or system.

However, the company’s fast growth at times—it grew to a chain of hundreds of stores and showed up on the stock market—made it a victim of the winds of the industry as a whole. For example, the company’s stock suffered mightily in the face of weak sales in the year before the release of the PlayStation and Saturn—a year in which gamers likely were saving up for the next system on the market. The stock struggles, which were driven by weak sales, forced the company to reorganize and shut down a number of stores. By the time of the release of the Nintendo 64, the stock had surged—the next generation gave it a reason to thrive.

The company’s approach to selling used games was popular, however—so much so that the chain’s approach was widely emulated by competitors such as, according to FundingUniverse, Toys R Us. But while other competitors thrived on the latest generation of games, FuncoLand still was able to wring value out of older generations of games in the years before that market moved to eBay.

There was also more room for diversity in video game stores at the time. The market wasn’t just being driven by one or two standalone companies, nor were large chains the only players in the gaming market. FuncoLand’s focus on used games stood out in a market of new ones.

But consolidation eventually caught up with it, in no small part because of a reinvention on the part of its main competitor, Babbage's Etc. The firm, in 1999, started rebranding its stores GameStop with a stronger focus on used games, and the company soon sold itself to Barnes & Noble. This acquisition allowed for room to nurture the GameStop brand under a larger corporate parent, and it also set the stage for further acquisition.

And that’s where FuncoLand comes into play. In 2000, Electronics Boutique, the other main competitor in the game store space at the time, announced it would buy out Funco for $110 million, with the chain looking to maximize its access to used game inventory. Very shortly after the deal was announced however, Barnes & Noble swooped in, offered $161 million for FuncoLand, and ensured us a fate of faceless GameStop locations around the country. (Eventually, GameStop, which later spun off from Barnes & Noble, would go back to buy Electronics Boutique outright, creating the monolith we have today.)

The approach worked in some senses—certainly, GameStop is a much larger company than it would have been otherwise, and Game Informer wouldn’t have a circulation of more than 6 million copies if not for GameStop’s aggressive approach of tying the magazine to its loyalty program—but something about the basic purity of FuncoLand’s approach was lost in the mix.

For one thing, GameStop stopped buying and selling retro games in 2004, only starting to dip its toes back into the market in 2015. The move effectively pushed a lot of gamers to eBay, where game values, soon enough, went nuts.

You have to wonder if things would have shaken out the same way if FuncoLand, with its infamous lists and thoughtful approach to used gaming, stuck around.

“How do they treat rare games today? Eventually, to clear more shelf space for new titles, many stores started to rip up and throw away the boxes for cartridge games. Some still keep the boxes for the few games they receive, but they don't alter the price if no box is present. And to the great chagrin of collectors, the box is usually pasted with stickers—price on the front, a new UPC code on the back, and maybe even clear stickers that seal the box shut. All of these can ruin the box if not removed with great care.”

— Chris Kohler, a video game journalist who currently works as an editor for Kotaku, writing on the post-FuncoLand state of used games in his 2005 book Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life. Kohler noted that GameStop in particular had seemed to disregard the value of old games in the chain compared to Japanese game stores. “This would never, ever happen in Japan,” he stated, adding that the situation was worse with rarities. “They would balk at the practice of ripping up boxes and selling the unboxed copy at full price, or selling a scratched, bare CD for anything over a few dollars.” (To be fair, GameStop has improved its practices some in recent years.)

Every time I walk into a GameStop, I’m disappointed. I probably do it to myself, because I really only care about retro games, particularly those made before around 1996 or so, and I walk in, full of hope that they might have something that caters to me, the guy who likes retro gaming, but every time … nothing.

My quibble is not the only quibble about GameStop. There are many: They upsell too much; they’re too corporate; they won’t let you return your game without a whole lot of hassle. In a 2012 article at the defunct Planet Xbox 360, an anonymous GameStop employee discussed how the company’s aggressive approach to buying, selling, and reselling used games harms the game market in the long run.

“So the question then is, if GameStop is making all of this money on the games being used, then how are the people that make the games making significant profits?” the 2012 piece ponders. “The answer to that question has created enough controversy in the gaming industry that publishers are going to extra lengths to combat used games with online passes and rumors […] abound that the future generation of console systems may lack the ability to play used games altogether.”

To be fair, used games, books, and movies have always cut the creator out of the loop; that’s how copyright works. But now we’re at a point where companies can actually do something about this by selling their products digitally—or in the case of a system like the Super NES Classic, reselling the digital products in a new physical form.

I have to wonder, as well, if this push toward digital-only games would be so extreme if the competitive picture was different. While there are other chains that have cropped up to compete with GameStop in small ways, such as the excellent 2nd & Charles, and mom and pop stores are obviously still a thing, consolidation effectively burned off the fingerprints of all those old companies like EB Games and FuncoLand. The diversity of companies helped make gaming stronger; without them, we have one massive chain, a bunch of big-box stores, and online stores. For the gaming industry, that lack of diversity can’t be healthy.

The consolidation is so complete that if you search for FuncoLand on Wikipedia, it brings up the GameStop page that barely even mentions the existence of FuncoLand, despite the company having a distinct history separate from the firm that ate it up on its long slog into 900-pound gorilla of used gaming. And if you go to the GameStop talk page, there is a contingent of users that think there should be a separate FuncoLand page; it hasn’t happened, even though the issue came up a decade ago.

This was a company that existed for more than a decade, that sold for $160 million, that effectively popularized the used game market, and that played a significant role in many gamers’ formative experiences, and we’ve basically erased it from our digital record because of a merger that happened nearly 20 years ago.

I realize that FuncoLand is an old product, one that was long ago used up, but it’s hard to miss the irony. Hopefully this piece makes up for it.

:format(jpeg)/2018/03/tedium032918.gif)

/2018/03/tedium032918.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)