They Steal Horses, Don’t They?

Discussing the rise of organizations that fought against a very specific type of crime: The theft of horses. However, that wasn’t all they were doing.

“At first he thought it a joke, and sat down to wait until the joker should return the animal. He waited an hour, but the horse was not returned. At last he was forced to walk home.”

— A line from a 1909 New York Times article discussing an unusual situation that befell Vital Binnett, the president of the Cahokia, Illinois, Horse Thief Detective Association. Binnett was holding a celebration in honor of driving out horse thieves in the area when all of a sudden his horse went missing. As you might have figured out, some jerk stole his horse! According to the article, Binnett reported the theft to authorities, “but the humor of the situation drove away his wrath, and he told the authorities he was doubtful he would prosecute should the thief be captured.”

(Wikimedia Commons)

Why the horse detective was a quiet-yet-important wrinkle of American history

Hearing the phrase “horse detective association” makes one think of a bad script that’s fallen into the hands of BoJack Horseman at some point, but as unusual as it sounds, it reflects a general need of the early U.S.

Simply put: Nobody likes when their stuff is stolen, especially people who have major investments. And during Colonial America and just after, the biggest investment that many people had was their horse.

And since a lot of people had horses, this meant that it made sense to create organizations to that allowed horse-owners to take a look after their investments. In a way, these organizations were akin to a combination of neighborhood watch and vigilante organization, with perhaps a touch of both the Pinkerton National Detective Agency and the Wild West.

Bullets, Badges, and Bridles, a 2013 book on the topic of anti-horse-thief organizations by John Burchill, explained that the spread-out nature of the early colonies made these societies desirable:

Most of the colonists lived in small communities, which meant that the detection of a crime, and often the person responsible, was not easy to evade. A crime committed by someone outside the community, a stranger, often would increase the fear associated with crime. Horse theft, as a crime in general, often included removing the animal from the area to be used or sold without fear of being discovered. Given the typical modus operandi of this crime, therefore, apprehension required pursuit, if the animal was to be recovered. Fear of the often unknown thief, the direction of travel, and the many possible outcomes in a confrontation, required several people, a society, be involved in responding to the crime. And this method of response was familiar to many.

Over time, these groups became more prominent and gained wider exposure and authority. For example, many states would pass laws effectively giving the societies the power to arrest and fight certain types of crime—something that became attractive in a number of states where the populace tended to be more spread out. Mostly, this meant Midwestern and Plains states like Missouri, Nebraska, Indiana, and Wisconsin, but even New York and New Jersey had such laws. In some ways, depending on the law, these individuals had even more authority than the local sheriff, in that they could cross county lines to catch a horse thief.

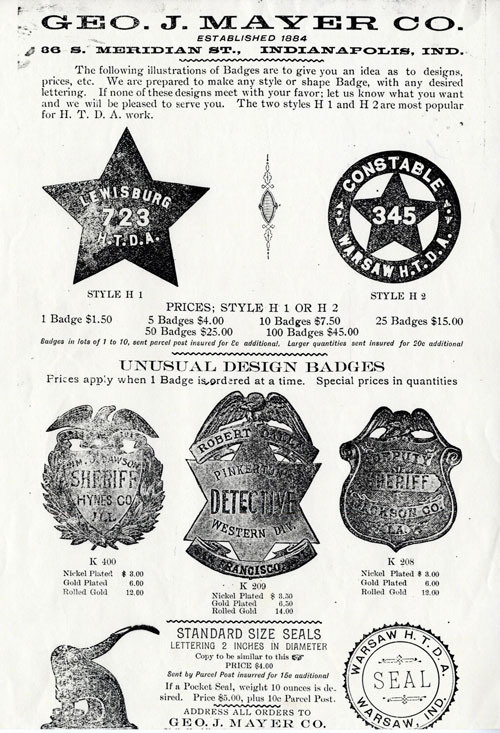

One of the more prominent of these organizations is the National Horse Thief Detective Association, an Indiana-based group that had significant reach within that state especially, with many local affiliates. The organization had all the hallmarks of an organization that detected horse thieves, including the existence of badges that look not unlike sheriff badges.

The organization came to life as an offshoot of an organization called the Council Grove Minute Men. Facing a highly organized and difficult-to-prosecute situation with horse thieves, the association was born in the late 1840s as a response to a challenging problem.

Examples of badges used by local horse thief detective associations and similar groups. (Wabash College)

Indiana soon gave such groups broad authority to act as de facto law enforcement officials, doing so nearly a decade before any other state, according to the 2005 book Citizens Defending America: From Colonial Times to the Age of Terrorism. Per an oral history of the association collected in a Wabash College archive:

“Their purpose was ‘to assist each other to suppress horse-stealing, house-robbing, pick-pockets, and all other thieving; and to regain the stolen horse or horses and all other property and to apprehend the thief or thieves,’” the history stated. “Note that, although the stress was on horse stealing, other types of crime were mentioned. This left the door wide open and during the time the horse thief movement was in existence it tried to extend itself into other types of law enforcement.”

This situation, as you might assume, was not ideal; for one thing, class was a factor for these organizations. Not everyone could afford a horse back then, naturally limiting the type of people who would join a group like this. And the authority of these groups perhaps spread too far; certainly such authority made some sense in rural counties before the age of the automobile, but it likely allowed for some degree of abuse of power.

On the other hand, though, it gave local communities the ability to take on the scourge of horse thievery.

So, it’s worth asking: Why do we know so much about the Wild West from popular culture—from the Alamo to the OK Corral—yet know so little about so-called horse detectives? Clearly they’re cut from the same cloth, right?

At least in the case of the Indiana organization, it may be because of what was done in the horse detectives’ name.

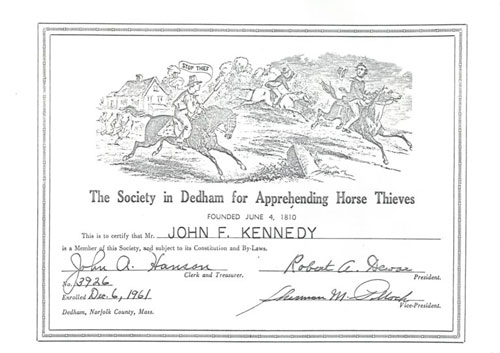

Yes, John F. Kennedy was a member of The Society in Dedham for Apprehending Horse Thieves. So was just about every other president of his era. He probably didn't catch any horses, though. (JFK Library)

Five real organizations that fought against the practice of horse theft

- Anti Horse Thief Association. This organization, perhaps one of the most prominent of its kind, was national in nature with more than 30,000 members at its peak and chapters in many Midwestern and Plains states, along with Texas and Oklahoma.

- The Society in Dedham for Apprehending Horse Thieves. This long-running organization, based in Dedham, Massachusetts, is shockingly still active, and counts numerous former presidents among its membership—along with a lot of other people. That’s because it’s a really easy organization to get membership in, and anyone can nominate anyone else. Effectively a social club at this point, it hasn’t actually caught many horses since it was founded in 1810.

- The Mutual Association for the Suppression of Horse Stealing. This Westchester County, New York organization, formed in 1815, counted at least one literary celebrity as a member—Washington Irving, who joined the organization in the 1850s, and whose knowledge of the horse stealing trade was colored by trips to the western frontier, where horse theft was common. The group ultimately disbanded in 1874.

- Red Hook Society for the Apprehension and Detention of Horse Thieves. A quote from a 1990 Associated Press article, uttered by then-president Woody Klose, says everything you need to know about this New York group: “It's got to be the greatest organization in the world. It meets just once a year and we haven't had a horse theft in years. Thieves are so terrified of us that they leave our horses alone.”

- Norton Detecting Society. According to Bullets, Badges, and Bridles, this organization, full name “Norton Detecting Society Formed for the Purpose

of Detecting Horse Thieves and Recovering Horses,” was one of the first associations built around fighting horse theft, dating to 1797, though the Massachusetts organization wasn’t the absolute first. That honor goes to the Northampton Society for the Detection of

Thieves and Robbers, also based in Massachusetts. These early groups were so amazing at naming their anti-theft organizations.

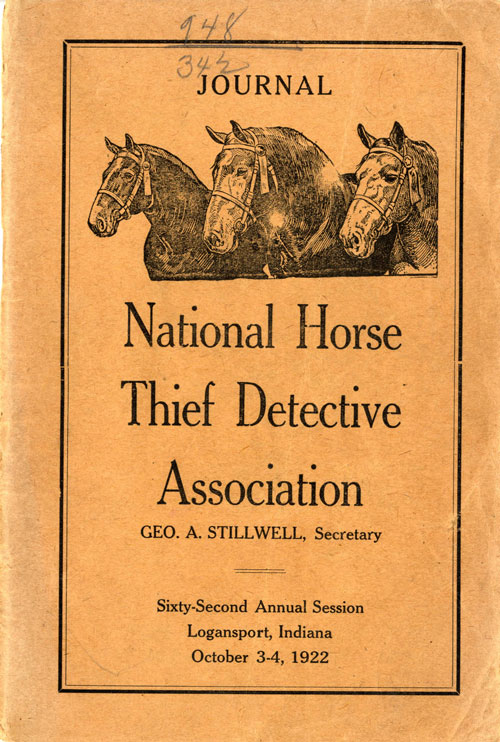

Around the time of the 1922 annual meeting of the National Horse Thief Detective Association, the group became associated with an ugly cultural wave. (Wabash College archives)

The uncomfortable history that hastened the end of the National Horse Thief Detective Association in Indiana

As you might guess by the fact that I’m writing about the National Horse Thief Detective Association in the past tense, the organization is no longer with us, having faded from view starting in the 1930s.

You might assume that due to the date of its fadeout that the demise of the organization might have something to do with the automobile, which was well established by that time. And to be fair, cars were probably a factor in the decline of the primary horse detective organization, but it wasn’t the only one, and it likely wasn’t even the biggest factor.

The biggest factor takes us to a dark time in American history, particularly in Indiana. During the 1920s, the vigilante spirit that once drove the organization ultimately turned ugly, in no small part because of the Ku Klux Klan, which was seeing a revival nationwide around this time, with Indiana one of its most prominent strongholds.

D. C. Stephenson, who served at one time as Grand Dragon of the Indiana KKK, wanted to take advantage of the broad legal precedents afforded to Indiana’s horse thief detective associations, which were still on the books but generally forgotten in the era of the automobile, and tried to have KKK members infiltrate the group. Opinions are mixed as to how far they got—retrospectives of the association often imply that local chapters were easier for the KKK to mold than the national group, which was based in Indiana—but the situation nonetheless colored the later perception of the association.

Latching onto threads of racism and anti-Catholic sentiment at the time, the Klan quickly gained momentum in the state as a result of Stephenson’s organizing skills—with a membership at one point topping half a million members—but he was soon implicated in a brutal assault on Madge Oberholtzer, an adult literacy advocate and government employee in the state. Oberholtzer died of the injuries she received in the attack as well as poison she took while in Stephenson’s captivity. However, she did not die for a full month after the attack—which gave her time to directly implicate Stephenson in a written statement.

As The Indy Channel reported in a retrospective on the incident, the murder shined a light on the ugliness of the Klan, which Stephenson believed would shield him from prosecution. (He was widely reported to have said the phrase “I am the law in Indiana” to his victim.)

Stephenson spent roughly two decades in prison for his crimes. (via The Indianapolis Star)

The criminal case and the attention it drew quickly undid the KKK’s influence in the state—and the country at large—especially after Stephenson, denied a pardon for his crimes, started leaking the names of prominent politicians on the Klan’s payroll, including Indiana Governor Ed Jackson. (In 1928, the now-defunct Indianapolis Times won a Pulitzer Prize for its unraveling of what might have been the biggest scandal in the state’s history.)

Attorney George Brattain, whose grandfather served as a juror in the case, noted to The Indy Channel that the saga became something Hoosiers simply didn’t want to talk about after the fact.

“I think the Klan left such a stink in Indiana,” he said. “It's the foulest-smelling beast we've had to deal with in Indiana. And it created a deep, deep fear in Hoosiers. For a long time Hoosiers would not even talk about the Klan. Not until the 1970s-80s, really. There's still a lot of confusion and anxiety about it.”

It’s probably for this reason that the National Horse Thief Detective Association, stained by its tie to the Klan, faded into history. The group tried rebranding in the wake of the scandal, becoming the National Detective Association, but it ultimately wasn’t enough to save its reputation. The state legislature took away the associations’ broad policing powers in 1933, partly out of the concern that another D. C. Stephenson would appear.

The fraught demise of the association has in some ways complicated research into its history. The Indiana organization, despite its onetime prominence and clear tie to the state’s history, doesn’t have a Wikipedia page unlike some other prominent horse-detective organizations, and getting descendants of the organization’s members to talk about an organization tied to one of the state’s darkest moments isn’t exactly easy.

“Today, if your grandfather was a member of the Ku Klux Klan, you're not going to tell anybody,” researcher Paul Craig said of the organization in 2012 comments to the The Huntington County Tab.

So the task has fallen onto local libraries and archives, which have broad collections of information on the organization and its local affiliates, and amateur researchers like Craig, who see their role as saving history that otherwise would not be saved due to the discomfort it creates.

Let’s hope that this mention of the organization helps expose it—and its messy, but important, story—to more people.

1997

The year that Stolen Horse International, an internet-enabled take on the horse thief detective concept, first went online. (The organization is also known as NetPosse.) The husband and wife team of Harold and Debi Metcalfe became passionate about the issue because they were victims of horse thievery themselves. After the couple’s horse, Idaho, went missing, they spent nearly a year looking using a variety of means, including digital. They found Idaho, fortunately, and in 2003, Stolen Horse International became a nonprofit.

As the existence of Stolen Horse International proves, there remains a need for horse watchdogs even into the modern day. Most people may use cars these days, but plenty of folks still have horses.

And as life has become more sophisticated, so have the crimes. Recently, the tale of a veterinary student and apparent chronic horse thief has gained a measure of attention.

The scheme of the accused thief, Fallon Blackwood, worked like this: The student would offer owners a free home for their aging horses, but instead of actually helping them out, she would actually sell them to slaughter.

Blackwood’s elaborate thefts drew attention thanks to the power of social media. After owner Lindsay Rosentrator lost a horse named Willie to the scheme, she started a Facebook page called “Finding Willie.”

Rosentrator teamed with the Stolen Horse International, and soon, the ugly scheme was exposed. Dozens of horses and their owners became victims in the scheme. It’s the largest case of horse theft in the 20-year history of Stolen Horse International.

So, no, horse thefts look nothing like they did in, say, 1890. But the people fighting to keep their horses safe are just as passionate.

:format(jpeg)/2018/05/tedium050818.gif)

/2018/05/tedium050818.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)