Make Some Noise

Sound cards like the Creative Sound Blaster were the missing element that computers needed to take on multimedia. Then, they faded from view. Here's why.

Hey all, Ernie here with a classic (though lightly updated) Tedium piece about one of the defining pieces of ’90s computer technology: The Sound Blaster. Crank it up!

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

The business oversight that created the market for sound cards

The IBM PC was created squarely for the business market, and while such machines were far more powerful than most video game consoles of the day, two places where they fell flat were video and audio.

The reason? At the time of the machine’s initial release—particularly before clones came about—there was no real business case for a computer to support a wide array of graphics and sound. The graphics-heavy GUI as we know it was still years from becoming commonplace, and it wasn’t like you needed robust sound capabilities when writing documents or crunching numbers.

While early IBM PCs had speakers, they effectively existed only to allow for error messages—and as a result were heavily crippled. As developers got their hands on these devices and moved beyond purely business programs, they eventually figured out ways to stretch this incredibly limited palette of sound using a hack called “pulse width modulation.”

This eventually allowed for the PCs to make 6-bit digitized sounds—not enough, say, to play a pop song through your speakers, but plenty to make music for your average King’s Quest game.

IBM, nor many early clone-makers, were really interested in improving the sound element much for the business computers, but they did try to make overtures to the home market. IBM’s PCjr, released in 1984, had better sound capabilities, thanks to its use of the Texas Instruments SN76489 chip. You may not have owned a PCjr, but you’ve probably come across a SN76489, as the chip was used in many video game systems—both of the arcade variety and in home consoles like Sega Master System and Genesis. But the PCjr’s lack of compatibility with PC software, along with its inability to play games very well, killed the machine on the market.

IBM’s failure to improve the sound on its early machines left an opening for others to step into. At first, this meant buying a machine that wasn’t IBM compatible. Atari’s early computers, for example, used a capable sound chip it affectionately named “Pokey”. Later, Commodore’s Amiga, with its four-channel “Paula” chip, helped the computer build its reputation as a multimedia heavyweight.

Eventually, though, peripheral developers in the PC world spotted an opportunity of their own.

nine

Why the Sound Blaster broke through

The Sound Blaster wasn’t the first attempt to create decent sound on an IBM PC. In fact, it wasn’t even the first attempt by its creator, Creative Technology, to take on this market—it made its first attempt in 1987 with the launch of its Creative Music System, then in 1988 with its Game Blaster card.

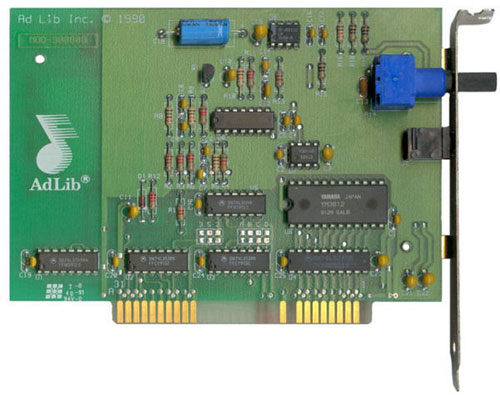

Nor was it the only major player in the market. Also in 1987, a Canadian company called AdLib was the first major player to the musical computing market, and its device proved an early success. These cards relied on the Industry Standard Architecture, or ISA, expansion slots that had been common on IBM PCs since their 1981 release.

The complexity of this approach might sound a little surprising to those who missed the early PC era. Unlike a USB device that you might plug into your laptop, these expansion slots (which you had to open your machine to access) were fairly large and could generally just do one or two things. So one card might be a modem, and another might add a printer port to your machine. Desktop machines tended to only allow for two or three of these cards, while a tower could take half a dozen or more. But because you were plugging these cards directly into the motherboard, the result was a notable speed boost compared to an external device.

Complicating matters at the time was that peripherals didn’t just work when you plugged them in—they required complex drivers, often a new one for every single program you installed. It was pretty much the opposite of “plug and play.”

Anyway, as we mentioned earlier, AdLib’s card relied on the Yamaha YM3812 FM synthesizer chip, which allowed it to create high-quality synthesized music. However, it couldn’t play any type of audio file you threw at it, because it didn’t support pulse-code modulation, or PCM. (PCM is the secret sauce that allows digital devices, like CD players or computers, to handle analog audio.)

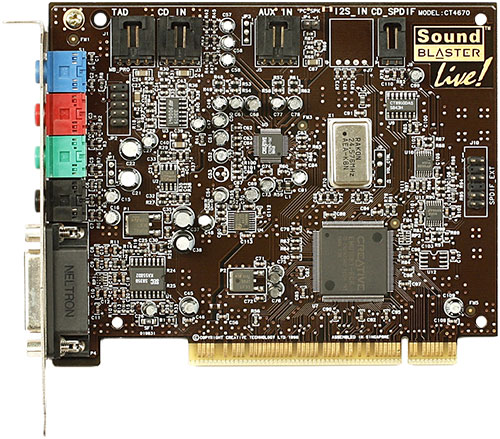

Creative wasn’t the first mover in the sound card market, but much like the clone-makers of the era did, the company took advantage of the fact that most computer chips weren’t proprietary. In other words, the AdLib wasn’t using unique chips, so Creative used those same chips and improved on AdLib’s offering slightly, launching a fully compatible card with PCM support.

And because Creative was building its devices in Singapore rather than Canada, its production costs were a lot lower. It wasn’t perfect—it could only play sound samples in mono, not stereo—but it was a huge leap forward for computer audio, especially on the PC. And Creative did it using off-the-shelf parts.

(Here’s what it sounded like, by the way.)

On top of this, Creative made some smart strategic moves—it worked with a bunch of major game publishers to ensure that they supported the Sound Blaster natively, and also made drivers widely available to developers. Further, Creative added a game port on the back of the sound card—taking advantage of the fact that most computers of the era didn’t have game ports—which gave gamers an incentive to buy.

The result was that, within a year, the Sound Blaster had become the de facto standard for the PC industry, and over the next few years, the company was able to iterate on this initial success, creating a product line that led its market for more than a decade.

“In Singapore, the no U-turn without sign culture has permeated every level of our thinking and every segment of our life. This no U-turn has created a way of life that is based on rules. When there is a U-turn sign or when there is a rule, we can U-turn. When there is no sign, we cannot U-turn. When there is no rule, we cannot do anything. We become paralyzed.”

— Creative Technology founder Sim Wong Hoo, writing about the “No U-Turn Syndrome” that he claimed had permeated Singaporean culture. Sim’s point, first explained in his 1999 book Chaotic Thoughts From the Old Millennium, is essentially his way of arguing that people from Singapore are often waiting for someone to tell them what to do before they take any action—something he argues shows up in driving, as Singaporeans won’t take a U-turn unless explicitly told. Sim, who built a reputation as a business maverick in the culturally-conservative Singapore, argues that the mindset of inaction is incompatible with the modern business world. “We are moving faster and faster into many uncharted territories, where there are no rules,” he adds. “We do not want to be paralyzed by waiting for the rule to be formulated before moving—it will be too late.”

These days, Creative is still active in the technology space, though perhaps with a smaller profile than it had during its ‘90s heyday. It was an early competitor in the MP3 player market, hoping to take on the world with its Nomad device, but things changed one day when Apple decided it wanted to get in on the market itself.

Not that Creative didn’t have passionate supporters.

“No wireless. Less space than a Nomad. Lame,” Slashdot founder Rob “CmdrTaco” Malda infamously remarked about the iPod at the time.

As for its bread and butter, the Sound Blaster is still a centerpiece of the company’s offerings, though a decision by Microsoft to effectively stop supporting hardware-based sound cards starting with Windows Vista—as well as improved computing power in general—turned sound cards, once a key purchase for any PC owner, into something that was no longer necessary. If you have a headphone jack, why do you need a dedicated sound card? Most people didn’t have an answer.

Creative got around this problem by classing up its offerings—going back to its roots as a luxury for gamers. And because most people these days are more likely to own laptops or tablets than towers with room for extension cards, most Sound Blasters the company sells these days aren’t sound cards in the traditional sense. Instead, they’re more like mini-amplifiers that you put on your desk or in your pocket. They often support Bluetooth, and some of them, like the Sound Blaster X7, sell for hundreds of dollars.

But the company is showing willingness to stretch beyond its corporate expectations. The company, for example, makes tiny-but-powerful mixers that effectively work as recording studios.

But it’s Creative’s most audacious recent product—an elaborate no-compromises soundbar for television sets called the X-Fi Sonic Carrier—that has people talking. When it was first announced, the asking price was an absurd $5,000; the manufacturer’s suggested retail price on the device ended up around $5,800—though the device can be had at a budget-minded $3,999.

The webpage for the Sonic Carrier, which is one of the longer non-Wikipedia pages I've run into in recent years, bludgeons you with details about its amazingness. “We have created a work of art so magical, so magnificent, so mind-blowing, industry experts have dubbed it the ‘Soundbar of the Gods,’” the site says.

It seems like a surprising move for a company that once sold sound cards by the truckload. But it actually fits pretty nicely into Sim Wong Hoo’s stance against the “no U-turn without sign culture.” Long story short, sign or no sign, Creative is making a U-turn.

“Two years ago, I put my foot down,” Sim told The Straits Times last year. “If we are putting so much effort into low-end products that don't give us the returns we want, shouldn't we focus our efforts on the high-end products that people can appreciate at a higher price point, albeit in a smaller market?”

Reviews seem to suggest that the more ambitious sound approach might be the right move for Sim and his company—TechRadar recently gushed about the Sonic Carrier, stating “specs can only do so much justice to this soundbar.”

Sure, it sounds over-the-top, and it probably is, but this guy has earned the right to sell $6,000 speakers.

:format(jpeg)/2018/01/tcfuz14f6ut76tpzgnqh--1-.gif)

/2018/01/tcfuz14f6ut76tpzgnqh--1-.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)