The Chinese Robocall Blues

Like spam messages, robocalls aim for the broadest possible audience in an effort to get someone, anyone, with its scam. And both are annoying as heck, too.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

1978

The year of the first incident of computer spam. (Happy 40th birthday, spam!) A guy named Gary Thuerk, a marketer for Digital Equipment Corp., had the bright idea of using ARPANET to promote the fact that DEC’s newest hardware could use the primitive computer network. The idea, while clever, went off the rails because Thuerk sent the message to so many people that the message couldn’t fit all of the recipients. Which meant that Thuerk sent it again to the people that didn’t get it. The message quickly created a series of complaints. “I knew I was pushing the envelope,” Thuerk admitted in 2007. “I thought of it as e-marketing.”

The immigration lawyers that uncovered a lucrative business opportunity by covering Usenet in spam

The reason why I see a clear lineage between the weird Chinese robocall I got recently and the prose-based spammy items that fill up inboxes is because it reminded me of one of the first prominent examples of spam—a mid-’90s saga that set the template for kajillions of spam messages to come.

If you go through your email spam folder and read examples of messages that you get on an average basis, you’ll see a common thread—quite often, someone is trying to trick you, or at the very least, take advantage of you. I personally deal with dozens of messages per week featuring people asking for a guest post in this newsletter for the goal of gaming search-engine algorithms.

But there’s also a tendency for spam to be built around things that most people don’t need. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is great and all, but if you’re not selling food, shelter or creature comforts, you might just struggle to find new clients.

This is a problem that immigration lawyers might have. If you’re looking to enter a country, the process of getting a green card can be tough, but it’s relatively rare, with renewals only happening once a decade or so; the average person might only work with a particular immigration lawyer once. Most people don’t need green cards, but those that do really want them.

Perhaps that’s the line of thinking that led two such immigration lawyers, Laurence Canter and Martha Siegel, to Usenet. In 1994, the husband and wife legal team adulterated the still fairly pristine confines of Usenet to push a message far and wide.

That message? The green card lottery was coming. In 1994, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services put into effect a new system for distributing green cards, an annual lottery that picks a very limited number of permanent residents to live in the United States—50,000 out of a estimated 14 million applicants. The program, called the Diversity Visa program, was generally free to apply for and had low odds of green card success, but the general lack of awareness of the program created an opportunity of sorts—a couple of immigration lawyers without their scruples could take advantage of this lack of awareness and make some money off the deal.

Which is what Canter and Siegel did. But instead of using old tactics to draw attention to their ploy, they used technology—specifically by promoting their services on Usenet, the Reddit-like open protocol that was susceptible to aggressive third parties. They didn’t particularly care where the message was posted, just where it ended up. In other words, it was spam through and through.

But unlike a lot of modern spammers, you could very much argue that Canter and Siegel were quite savvy in a traditional sense. They saw Usenet as a place to market their basic ideas. And while it was annoying and exposed them to significant backlash, it also was objectively successful at what it was trying to do: the couple claimed that the ads earned them $100,000 in business.

Canter and Siegel had a reputation for being troublemakers in the world of immigration law long before they discovered their clever tactic for barraging hundreds of thousands of people at once. This particular situation, however, went too far, and ended up costing the couple their law license. In a 1999 retrospective piece for Wired, lawyer and tech security expert Ray Everett-Church, who then worked at the American Immigration Lawyers Association, noted how the cheap tactic personally made his life hell.

“I realize now that I was one of the first computer professionals to experience the feeling of dread evoked by a flood of spam complaints,” Everett-Church recalled. “I have never quite forgotten that feeling, and it is part of the reason I have spent so much of these last several years combating Internet abuse.”

But even without a law license, the sheer novelty of what Canter and Siegel had done meant that they had options: They managed to score a book deal, which may be the first and only time that anyone cared what a spammer had to say. Fittingly, the book was titled How to Make a Fortune on the Information Superhighway, putting it in the same territory as Free $tuff on the Internet.

I alas couldn’t find a version of the book online, but a summary of the book for sale on Amazon highlights the nut of the couple’s many ideas about marketing and getting rich. Here’s one such nugget from the summary:

The key to making money on the Internet lies in the opportunity it presents to present your goods or services to large numbers of people at a very low cost. There are currently in excess of 30 million people connected to the Internet, although nobody is really sure how many. About 10,000 more people are obtaining Internet access every day. Millions more users are expected to join the Internet over the next few years.

The fascinating thing about the statement is that, yes, this is true today. But it also highlights how primitively we thought about marketing in 1994. Data, basically the thing that makes the world go ‘round in 2018, was a non-factor at the time of the onslaught on Usenet.

In many cases, spam is a bludgeoning tool, with no distinct focus. It’s big data only in the sense that it’s designed to reach scale. Just like robocalls are.

“On a final note, just because you don't see something here doesn't mean we haven't already seen, dealt with, and filed a complaint about it. Really the best thing to so is delete it and move on.”

— A statement on a MIT webpage, discussing the spam that hit the university’s servers circa 1999. These messages, which vary wildly in nature and in tone, would put strain on the university’s server in numerous ways (think of Elf Bowling) and would often prove time sucks for the school’s IT staff. In case you’re looking for a time capsule of what old spam looked like before automated phishing links, links to counterfeit drugs, and obvious scams became the norm.

Political candidates didn’t invent robocalls, but they sure made them annoying

The federal government had already taken steps to ban the robocall before we actually bothered to give it that name.

In 1991, the House had considered a law to ban junk faxes, which sounds like a worst-of-all-worlds form of physical spam. The law, additionally, eyed a plan to take on automatic dialing systems, which evolved from a phone-system-sanctioned idea into an easy way for scammers and debt collectors to further their reach.

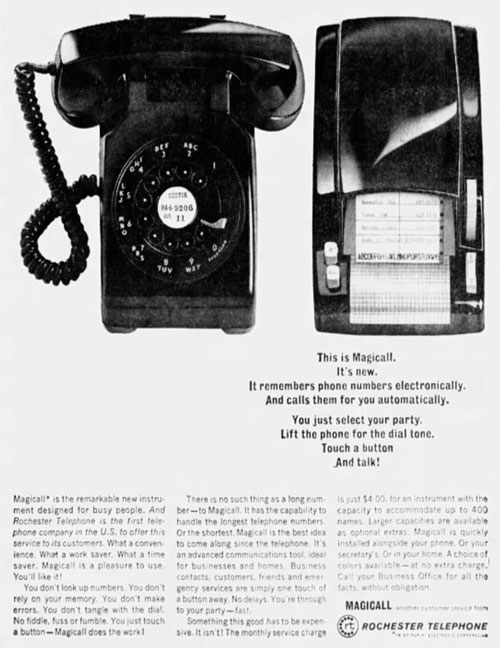

The Magicall, an early example of an autodialer. No automated messages, however.

That measure eventually became law—the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991—and has led the Federal Communications Commission to take the issue seriously ever since. Clearly, the issue has been on the FCC’s radar for nearly 30 years.

But what about the term “robocall”? That term, despite being so common, is very new—around 20 years old, in fact, with its first reference in the run-up to the 1998 midterm elections. One of the earliest references I found was in relation to a phone message created by Hillary Rodham Clinton that was used during get-out-the-vote campaigns in New Mexico.

The idea wasn’t totally new by that point, but political campaigns were uniquely positioned to take advantage of them due to the quirks of the 1991 law. Simply put, robocalls made under the guise of a political campaign are one of only a small handful of robocall types that are still legal. By the middle of 2006, the public was asking for relief—while in some cases, the politicians (including Clinton) were using celebrities on their robocalls.

However, as the FCC helpfully notes on its website, such robocalls are illegal on cell phones, though are specifically allowed on landlines. (So if you only have a cell phone, you shouldn’t be getting them, right?)

In fact, unsolicited robocalls to cell phones are illegal across the board, with only a few exceptions, such as in the case of debt collectors. Which poses the question: Why am I getting so many?

Long story short: There are a lot of scammers out there, and they’re not following the law to any reasonable degree. They’re often offshore, using cheap VoIP technology that allows them to make many calls for an incredibly cheap price.

And those scammers are looking for bait—often in the form of scams, which vary significantly in tone and nature. The Chinese immigration scam that I got a few weeks ago? That’s fairly novel as far as spam calls go, but it’s far from the only kind out there. You may remember the travel scam Heck, they’d be happy if you just picked up your phone to confirm that your number is legitimate and they can call you again.

If your doctor’s office robocalls you, it’s because you’ve given your permission. Nearly everyone else is trying to scam you.

What I think is interesting about modern-day robocalls is how similar they are to early spam, where there was much more spraying-and-praying going on, and much less phishing and dissonance.

Marketing, at least on the internet, has evolved significantly in the roughly 25 years since we first gained a modern example of what spam would become. There’s much more data involved, so much more sophistication. While certain types of spam likely still do the trick, in many ways, the “spam” that has the most effect is the stuff we explicitly let into our inbox with our own personal knowledge. Our spam filters—both in our brains and in our tech tools—are just a little bit smarter.

(By the way, if you’ve been seeing a lot of updated privacy policies recently, there’s a reason for that—the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, which takes effect less than two weeks from today.)

Looking at my own spam folders right now, I see a lot of things I signed up for a long time ago (or at least I think I did). There are some phishing links in there, but what I’m not seeing are the traditional things that you’d consider spam—the long-lost princes who have some money to offload, the Nigerian 419 scams, the ads for the kind of drugs Bob Dole once hawked on television. I definitely didn’t see a green card lottery ad in there.

A lot of the robocalls we’ve seen hit our phones in the last few years have been along the lines of those early spam messages—an offer you can’t refuse, an awesome deal on something, potential help that sounds promising until you spend 30 seconds doing your own research.

Considering the fact that illegal robocallers don’t have anything to target with beyond your phone number—if they did, robocall kingpin Adrian Abramovich wouldn’t have been fined $120 million by the FCC for spouting out 96 million robocalls in a three month period—it makes sense that they would focus on these broad schemes.

That said, the Chinese robocall I got recently, in its own way, reflects something of a turned corner. It’s an evolution to a later era of spam, where the spammers were just a little bit smarter, and a little more targeted with their messages. The move to specifically bury the scam behind a different language? That’s absolutely brilliant. It’s targeting without doing the hard work of actual targeting.

The reason why robocalls are becoming so prevalent these days isn’t just about the cheapness of calling random numbers on a list.

It’s because spam doesn’t work as well as it once did, and robocalls still work.

:format(jpeg)/2018/05/tedium051518.gif)

/2018/05/tedium051518.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)