Robotic, But Lovable

Alexa’s Interface is treated as revolutionary, but you might be surprised to learn of your favorite opinionated cylinder’s predecessors from the mid-1980s.

Hey all, Ernie here with a brand-new writer to the Tedium stable. John Ohno has some fun obsessions that will come out in this piece about robots. Strap in.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

“One question was asked time and time again: ‘What does it do?’ The contrary opinion was also voiced that a robot did not have to be useful—it merely had to be lovable.”

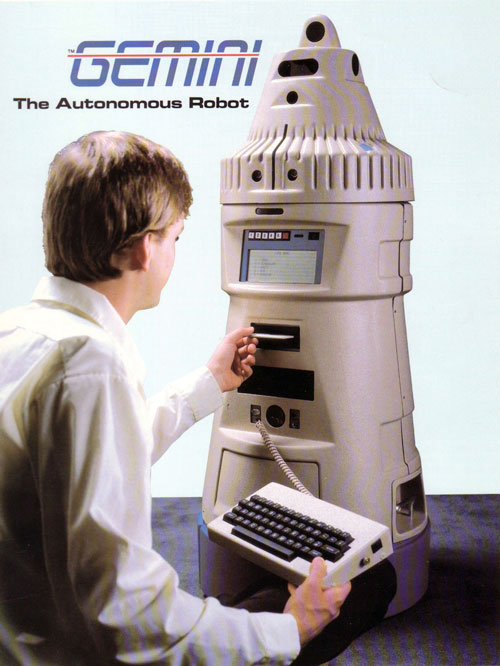

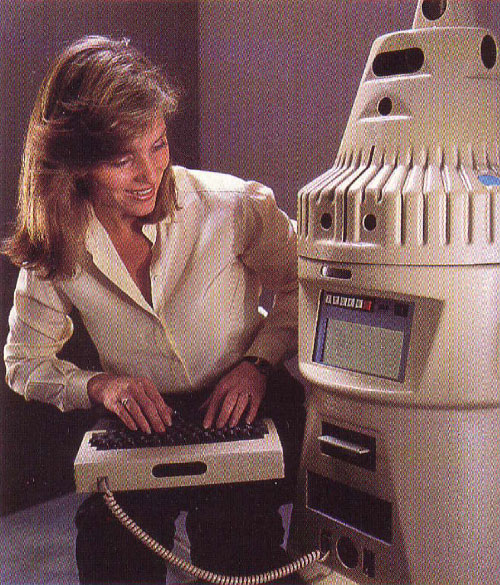

— A report on the First International Robotics Congress, held in Albuquerque in 1984. The robotics event directly inspired some of the earliest innovations in the robotics space, including the creation of the Arctec Gemini, which was brought to market in 1985 with direct inspiration taken from the 1984 event.

(via the Arctec Gemini brochure)

The consumer-focused robots of the ‘80s could do a lot more than you think

Based on the brochure for the Arctec Gemini, a life-size robot that could self-navigate, self-charge, and included an advanced operating system for its time, it had a lot more in common with an Amazon Echo than a robot in an old sci-fi film.

“Gather your family around you and say ‘GEMINI!’ loudly. The robot will respond with ‘GEMINI LISTENING!’ and automatically enter voice command mode,” the brochure stated.

The Gemini was the most technically advanced of the personal robots available in 1985, with features that remain impressive today. It not only spoke but took voice commands. It was self-charging, and retained a map of your home for navigation purposes, a feature that was only introduced into the Roomba line in 2015, 13 years and 5 generations after its introduction. It could sing with synthesized piano accompaniment, recite poetry, and connect to early online services like CompuServe.

(via the Arctec Gemini brochure)

Unlike today’s conversational interfaces, the Gemini took voice commands in an english-like programming language called VOCOL. This ultimately means that, where Alexa’s ability to respond to cues is limited to simple commands that vendors supply, Gemini owners were able to give much more complex and specific instructions, provided they were willing to read the manual. A fully-loaded Gemini also came with BASIC and assembly language support, and while users were not expected to be technically inclined initially, the documentation was designed to guide them to the point where they could add substantial features by themselves—and encouraged them to send their improvements back to the company.

“We are making available documented source code listings [...] at nominal cost so you can further your education and enjoyment of the GEMINI,” the device’s user manual stated, adding that users “will be able to develop new software and hardware enhancements.”

“Share these enhancements with us and other owners and we will do the same.”

Arctec formed in 1983 under the name Micromation, and built third party add-ons for Heathkit’s HERO. First released in 1982, the HERO was popular as an educational robot, and continued to be manufactured until 1995, spawning two more flavors. Where the Gemini was user friendly, with its speech input and support for BASIC, the HERO was daunting: while it had a speech synthesizer, the primary means of input was a keypad, and the only display was a six-character seven-segment display, akin to sticking the faces of two cheap digital watches together. One thing that most models of the HERO had that Gemini didn’t: an arm.

Arctec decided to bring their own robot to market in response to the First International Robotics Congress, according to Michael Fowler, an engineer who worked on the Gemini and agreed to be interviewed for this piece.

Gemini leaned harder into lovability than its competitors—the brochure emphasizes the idea that it would become part of the family, and claims “You will think GEMINI is really alive!”. Even though its support for home automation, its wireless access to telephone lines, and even its unusually large built-in display and wireless keyboard put it above its competitors on the grounds of utility, the most impressive features are essentially social: educational games, songs, and computer-generated poetry and stories.

This would have been in line with the general mood of the home robot side of the conference. Nolan Bushnell, founder of Atari, summarized his position on the subject of the utility of robots thus: “Fun sells.”

$25M

The amount in anticipated sales Androbot projected in 1984, according to an Inc. Magazine article discussing the Nolan Bushnell company and its ambitions. This projection was due in part to the $2,500 price tag of BOB, the luxury model. The company folded before BOB could be brought to market.

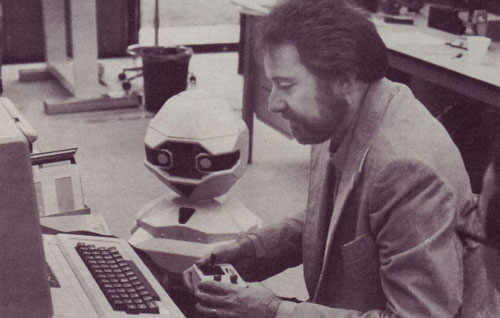

Nolan Bushnell, shown with an Androbot TOPO machine. (via The Old Robot)

Fun didn’t sell: Nolan Bushnell’s doomed gamble on friendly robots

Bushnell, Chuck E. Cheese already behind him, had formed what we would now call a startup incubator, and was at the conference to promote one of its early graduates, Androbot. Androbot had one project—TOPO—a squat robot resembling a cartoon ghost, which had no on-board computer and instead was remote controlled over radio from a nearby Apple II. Bushnell was betting a lot on the idea that utility didn’t matter: TOPO didn’t just lack the advanced features of the Gemini and the arm of the HERO—it didn’t even come with bump sensors. It was a remote-controlled chassis with a speech synthesizer.

The manual for the TOPO II put its functionality as such: “TOPO is a computer-controlled personal robot that can be programmed to “walk” over any level surface.”

Bushnell later described this generation of personal robots as “P.C.s on p.c.s—Personal Computers on push carts”, according to Patrick H. Stakem. This would have applied to Androbot’s B.O.B. and TOPO IV, models that were planned but never actually produced. The TOPO I (discontinued the same month as the First International Robotics Congress), TOPO II, and TOPO III were arguably not robots, but the relatively low price point made them popular. Despite delays with bringing most of its lineup to market and the limitations of those machines that did get produced, Bushnell’s experience inspired confidence and his marketing prowess sold units. Nevertheless, within a few years, all of these companies were shuttered.

“It is a lovable product that Nolan Bushnell believes will be irresistible to U.S. householders,” a 1983 Inc. Magazine article stated, continuing: “But with a record of good guessing that includes the development and marketing of Pong, the computer game that presaged today’s multibillion-dollar video madness, a person would need long odds to bet against Topo and its younger but more sophisticated brother, Bob, whose three internal computers are under development at Androbot.”

“I think until we can create a robot that is capable of doing anything a human can, on demand, it will never be enough.”

— Gemini engineer Michael Fowler, discussing the challenges involved in finding a market for his machine.

A video featuring an array of TOPO robots.

Why was the great robot boom of the early ‘80s actually a great bust?

The year of the First International Robotics Congress was the year of the Great Video Game Crash. At the time, and for years afterward, the crash made people wary of the entire video game industry. Today, the blame is often placed on then-industry-leader Atari’s tendency to ship broken or low-quality games. It may be that the personal robotics industry’s forgotten crash could also be laid at the feet of Nolan Bushnell’s business philosophy.

Androbot was the most visible of the personal robot brands, with ads showing flashy mockups of a large line of models, half of which were never made.

In a history of the company, robot collector and historian Rick Rowland put the situation as such:

In May of ’83 TOPOs were shipped and [many] were dead on arrival and then some developed problems. A local computer store here in Las Vegas purchased one and could not sell it. I bought it for pennies on the dollars.

According to Rowland, by the time the first industry conference occurred, the company was already on its last legs, having missed deadlines, delivered faulty products, and lost important staff. Androbot represented the economy end of the personal robot market, and perhaps had B.O.B. and the other mid-range machines (comparable in price and capability with the HERO) shipped, it would have made the industry more sustainable as people graduated from low-end machines to higher-end machines.

The budget version of the HERO, without the arm, debuted in 1984 for $1000, or $599.99 as a kit

Heathkit, because they were in the business of making general educational electronics kits, were able to continue manufacturing the HERO for another decade, and even returned to the brand in 2012, producing one last model as they were going out of business. Another high profile machine, the RB5X (whose capabilities and targeting were similar to the HERO), is still for sale from the original manufacturer. But high-end machines intended for home use, like the Gemini, didn’t survive.

According to Gemini engineer Michael Fowler, founder Jack Lewis anticipated that the company needed to sell 300 Geminis in its first year at a rate of $8,995 just to break even. “When it didn’t look like we would get anywhere near that, we lowered the price to $6,995,” he noted

The total number of assembled Gemini units sold, in the end, was only about sixty, compared with 800 RB5Xs, 120 TOPO Is (of 650 manufactured), and a whopping 14,000 Heathkit HERO-1s. The Gemini didn’t find its place in the home, as hoped. After financial difficulties, Arctec was shut down by its parent company late in 1986.

Fowler provides schematics, assembly instructions, and source code for the Gemini on his website, for those with the time and skills to put one together themselves. He maintains that the real trouble with Gemini’s sales is that Nolan Bushnell, when he bet on joy over utility, bet wrong.

“Our robot had many features that still haven’t been duplicated today,” Fowler recalled. “We had an autonomous robot that could self navigate, plug itself in to recharge, speak, sing, play music, recite poetry, recognize commands and a bunch of other features. We programmed it to act as an alarm clock, security guard, entertainer and tutor for the kids. It was very advanced.

But when people asked us ‘What can it do?’ and we would list its capabilities, they would always scoff. They wanted a something that could wash dishes and clothes, clean the house, and wash windows.”

As for Bushnell, it was ‘divine intervention’ (according to Robotics in Service by Joseph F. Engelberger). He (probably jokingly) claimed that Androbot failed because it attempted to create a machine in man’s image, and went on to be more successful manufacturing robotic pets of even lower complexity. Considering how much more closely Bushnell’s other high-profile robot, famous mutant rat Charles Entertainment Cheese, resembles a human being, I recommend Bushnell try to avoid angering ghost emoji in the future.

“Rub petroleum jelly on your glasses. Tie one hand behind your back. Put a mitten on that hand, and then pick up chopsticks.”

— Joe Engelberger, the inventor of the robotic arm, which was previously covered on Tedium, discussing the challenge of properly controlling the device during The First International Personal Robot Congress & Exposition.

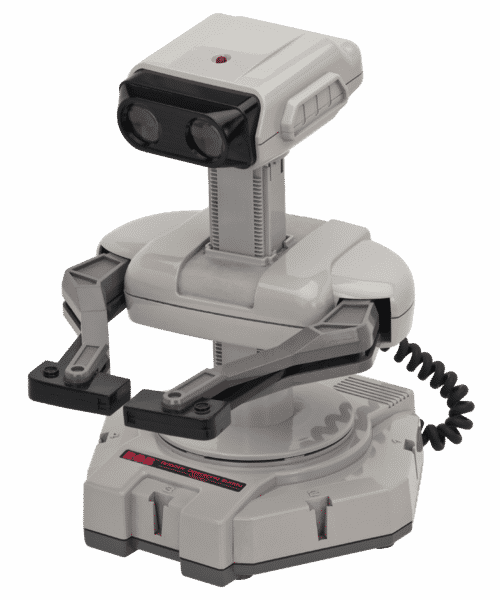

The most well-known artifact of the personal robot industry, ironically enough, is not part of the personal robot industry at all. When Nintendo brought the Famicom to the US in 1985, they rebranded it in order to dodge wariness about video games among investors, many of whom thought that the 1984 crash was evidence that video games as a whole were a fad whose time had ended. Part of the re-branding effort was a new name: Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES. Another was that it launched with an unusual peripheral: a robot called R.O.B.

R.O.B., although it was promoted alongside the NES’s official release, only supported two games & was notoriously unreliable. Like the TOPO, R.O.B. bet on the novelty of a robot in the home over any kind of utility. But despite being unsuccessful as a peripheral, it rode its association with Nintendo to all the way to icon status.

Maybe it’s not fun that doesn’t sell. Maybe it’s just underpowered robots.

:format(jpeg)/2018/05/tedium052418.gif)

/2018/05/tedium052418.gif)

/uploads/ohno_bw.jpg)