With ARM Wide Open

The story of ARM Holdings, one of our most important tech companies, is full of sheer luck, happy accidents, and a faded British computing icon.

Today’s GIF is a pan of the keyboard on an Acorn Archimedes, the first mainstream computer to use an ARM chip.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

“Clive is not particularly prepared to listen to other people’s ideas. He is, in a word, irascible.”

— Christopher Curry, the cofounder of Acorn Computers, speaking of British technology icon Clive Sinclair in a 1981 interview with The New York Times. Curry, who had played an important early role in getting Sinclair interested in the calculator and home computer markets, found his company the primary competitor to Sinclair Research in the British computer market in the early 1980s. Curry formed Acorn with Hermann Hauser in 1978 after Sinclair initially refused to follow up on the MK14, a kit computer launched by the company in the late 1970s. “It was quite a successful computer,” Curry told Practical Computing of the MK14 in 1982. “The next step was obviously a version that ran Basic instead of just machine code. That was where our ways separated, because Clive didn’t want to do it and I did.” Sinclair Research would go on to build one of the two most iconic British computers of the 1980s, the ZX Spectrum. Acorn would build the other.

The BBC Micro, Acorn’s first big hit, sold over a million units and became a mainstay of British schools. (Simon Inns/Flickr)

How Acorn scored the deal that solidified its early reputation

Given a long distance from the creation of the British television show The Computer Programme in the early 1980s, it’s stunning in retrospect to consider what the BBC was trying to do in 1981. In an effort to boost the country’s computer literacy, the public broadcaster wanted a standardized computer it could use to drive a multi-part TV series.

Not only that, it wanted that computer wanted it to hit certain specifications based on the different things it wanted to cover in certain episodes. For its time, the requirements were fairly stringent—it wanted to feature sound, graphics, and AI at a time when those three elements were still fairly primitive in mainstream computers.

Initially, the BBC worked with Newbury Laboratories, an offshoot of Sinclair’s 1970s firm Sinclair Radionics, to produce a computer to hit the broadcaster’s specifications, but the machine, called the NewBrain, was primitive even for its time, and Newbury eventually opted out because it believed it would be unable to hit the BBC’s manufacturing goals.

The BBC eventually expanded its pool of bidders to create a computer around the show, and reached out to numerous companies, including Sinclair Research (Clive Sinclair’s replacement for Sinclair Radionics, which went belly up after a funding deal with the government went south) and the competing Acorn Computers.

Acorn, which had built its first prebuilt computer, the Atom, in the prior year, had been working on a followup called the Proton that fit essentially all the BBC’s requirements. But it was still in the planning stages, with no actual prototypes built. Curry’s solution? He leaned on students at Cambridge to build enough devices to test in just four days. As The Register noted in 2012, system developers Steve Furber and Sophie Wilson worked against an impossible deadline, having the machine ready to go just minutes before the BBC reviewed the product.

Despite Sinclair being better known in the market and having more initial success, BBC went with Acorn’s design, a move that ensured the BBC Micro, as it would become called, would become the one used in schools around the country. It was a massive hit, and it was nearly impossible for the public to get its hands on a BBC Micro in its early years.

The ZX Spectrum, another icon of British computing. (alessandrogrussu/Flickr)

“Acorn got the BBC contract, for reasons that baffled Sinclair but nobody else,” The Guardian recalled in 2012 amid the BBC Micro’s 30th anniversary. “Their computer combined good industrial design with significant technological innovation.”

(Don’t cry for Sinclair, though: The ZX Spectrum was a huge hit in its own right.)

I could write more about this saga, but it’s been perfectly captured by the BBC in the 2009 docudrama Micro Men, which features

Alexander Armstrong as Sinclair and Martin Freeman as Curry. It’s on YouTube, and it’s very much worth watching.

When it comes to ARM, the real story is what happened after this point—what happened after the big success?

“Initially, we asked Intel for samples of their 80286 processor, but they refused. That’s funny, because ARM is now perceived as a competitive threat to Intel, and you can trace that all the way back to the seminal moment when they refused to give us those samples.”

— John Biggs, the cofounder of ARM, explaining to Engadget how a fateful move by Intel to disregard a request from Acorn to try out a 16-bit processor led the company to create the Acorn RISC Machine, its original 32-bit microprocessor, which paved the way for ARM as a company and line of chips. The chip first saw use in Acorn’s followup machine to the BBC Micro, the Archimedes.

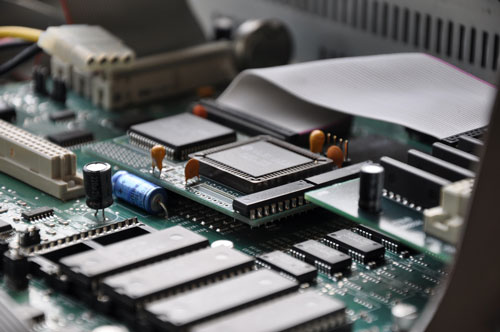

The innards of an Acorn Archimedes 5000, an early user of the ARM chip. (Blake Patterson/Flickr)

How the ARM chipset ended up becoming more fundamentally important than Acorn itself

The successor to the BBC Micro, the Acorn Archimedes, represented a sharp zag in an industry known for zigging, and while it came at a time when many companies were starting to standardize around specific computer models, the bet by Acorn to build its own processor architecture would prove prescient with time.

It also gave Acorn a starting point for a conversation about the machine’s future. The conflict with Sinclair, who had never strictly been into computers anyway, was old news by this time—Sinclair Research’s computing assets had been sold off to Amstrad in 1986.

Acorn, which had partially sold to the Italian computer firm Olivetti in 1985, would have to find ways to win over the market on its own, with the one-time gold rush of the BBC Micro in the past.

Like other firms that saw success during this era, it did so with technology. While the Apple Macintosh wowed computer enthusiasts with its interface and Commodore’s Amiga with its multimedia capabilities, the conversation about the Archimedes started from a place of speed. As the British magazine Personal Computer World asked on its cover in August of 1987, “Is this the world’s fastest micro?”

It might have been the fastest micro of its time—it was definitely the first reduced instruction set computer, or RISC, processor to show up in a computer targeted at the public—but it certainly wasn’t the most compatible one. While it included an emulation layer to support BBC Micro software, the machine introduced yet another new operating system to the world, an OS originally called Arthur.

In later years, Arthur would become known under another name: RISC OS, a piece of software that’s still usable in many computers today, most famously the Raspberry Pi, which uses variants of those same ARM chips.

The company would iterate on this system many times throughout the ’80s and ’90s, ultimately giving way to the RiscPC platform in 1994.

The RiscPC was fascinating because, while it was designed to look like a desktop PC in standard configuration, it was stackable, using a “slice”-based design that allowed for additional storage and functionality as needed. You could basically stack one computer on top of another, in a single case! The above clip from RetroManCave shows just how ambitious that system was in action.

While RISC represented the future for Acorn as a company, the company’s past would come to haunt it and ultimately hold it back. In 2012 comments to author Ellee Seymour on The Huffington Post, Chris Curry blamed a downturn in sales of the BBC Micro, combined with the fact that Olivetti was fundamentally ill-equipped to manage the company, for its later woes.

Why were they ill-equipped? To hear Curry explain it, Olivetti’s chairman, Carlo De Benedetti, had sent mixed signals to his sales staff—having told them, amid a deal with AT&T, not to sell any inventory that was not PC compatible—which was a problem because Acorn had a lot of unsold BBC Micro systems lying around that they were expecting Olivetti to sell.

“So they were told not to sell anything that wasn’t IBM compatible, and we were not,” Curry recalled. “We had Acorn’s own operating system, so it was a total disaster to have done this deal with Olivetti if we had known that they couldn’t [possibly] use their sales force to get rid of our stock.”

This, of course, meant that any innovation happening within Olivetti would be held back in the long run due to, essentially, corporate politics. While Acorn would create other products, like the spec system for Oracle founder Larry Ellison’s Network Computer, the company itself would fall victim to corporate disassembly in the years to come.

Fortunately, at least one part of the company found an escape hatch.

1990

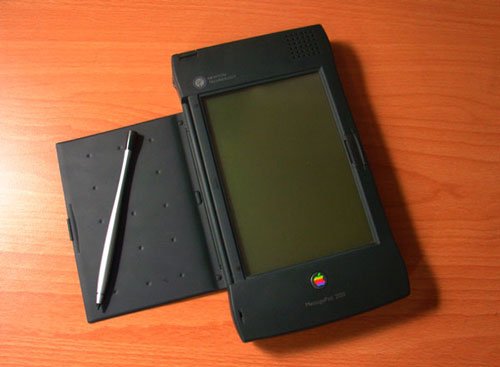

The year that Acorn’s ARM platform was spun off into a separate company, now called ARM Holdings. The firm was essentially created to separate the development of ARM from Acorn, and as such was created in a joint venture with Apple and chip manufacturer

VLSI Technology—allowing Apple to borrow the technology it wanted from Acorn (the chip, which it first used in the Apple Newton) while leaving behind what it didn’t (everything else).

Despite ultimately being a failure in the marketplace, the Apple Newton MessagePad represented a major turning point in ARM’s fortunes. (yggg/Flickr)

We wouldn’t have today’s ARM chips without a series of happy accidents

The decision to separate Acorn from ARM was remarkably visionary, and the fact that it is used in tens of billions of devices around the world—often through ARM’s brilliant business model of licensing the chip technology to vendors, who then build upon it and resell it—suggests that the chip, quietly, may be the greatest computing success story of the last 30 years.

Its success, however, highlights an improbable series of happy accidents that helped to define the chip in the face of the modern computing industry.

I already mentioned one: The fact that Intel failed to send sample chips to Acorn in the early ’80s, leading the British company to develop its own CPUs.

But there were others, including the fact that ARM was low power. That feature, a key reason we have the Raspberry Pi and other low-powered computers in 2018, was totally unintentional.

In his 2011 interview with Engadget, ARM cofounder John Biggs noted battery life was not a focus of RISC when they first started building. Instead, performance was. It just so happened though, that battery life came with the package deal.

“For a given amount of money, you get a great deal more performance. Or you can have slightly more performance for a lot less money,” Biggs told the website. “The low-power thing was a happy accident, which of course became important for handheld devices with limited battery life, but it wasn’t initially the prime concern when we started at Acorn.”

Another, somewhat less heralded happy accident had a lot to do with the fact that ARM Holdings came to life thanks in part to Apple.

These days, Apple is one of ARM’s biggest customers—having used ARM chips in the earliest iPods, through to its smartphones and tablets, and even in some of its laptops—but before that point, Apple also benefited financially from its investment in ARM. And that investment came in handy in the mid-’90s.

In 2011, Acorn cofounder Hermann Hauser revealed during a speech that Apple’s partial ownership of ARM, purchased for $1.5 million, was sold for $800 million over a period of several years—an amount that saved Apple from bankruptcy.

Larry Tesler, the onetime Apple exec who brokered the ARM deal, puts that data point on his resume.

The crazy part, of course, is that, if Apple had held onto the shares prior to the company’s $32 billion sale to Softbank in 2016, they probably would have made 10 times the profit on that investment—because Apple owned roughly a third of ARM Holdings upon its initial creation in 1990.

But considering it helped the company get back on its feet so that it could use more of those chips in its products and push forth the revolution that made ARM chips valuable in the first place, perhaps they made the right move.

They just made back the value in other ways.

In recent years, there’s been a movement to take the brands of old companies, revive them in modern contexts, and use them to drive crowdfunding campaigns. If you’ve been watching your favorite YouTuber complain about the Atari VCS, this is why.

Acorn has recently become part of that movement, thanks to an entrepreneurial move to market a smartphone featuring the Acorn logo.

Something tells me they didn’t build this.

This literally, and utterly, makes so much sense. Given the fact that the Acorn Micro C5 is likely to use an ARM processor or five, they could have slapped the Acorn logo on any phone out there and it would have been a homecoming. (The revived company, based on this page, has some bold goals long-term.)

But while this campaign had big goals, it didn’t get anywhere near them. In fact, the company raised just £4,925 ($6,603), just 1 percent of the company’s total goal for the endeavor.

On the plus side, at least its Indiegogo campaign isn’t getting accused of massive fraud, like the campaign for the ZX Spectrum.

That’s one competition with Sinclair that the modern-day Acorn would probably love to lose.

:format(jpeg)/2018/06/tedium060618.gif)

/2018/06/tedium060618.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)