That '70s Interactive TV

The story of Columbus, Ohio’s own QUBE Interactive Television, which—beyond breaking ground for cable TV—was social media for the ’70s, for good and bad.

Hey guys, Ernie here with a new writer for Tedium, a guy named Chris Tonn who wanted to talk about an awesome piece of television history that happened in his hometown of Columbus, Ohio. Perhaps it didn’t come to your neck of the woods, but you certainly benefited from it. I’ll let him explain. Thanks all!

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

Why Columbus? How technology and demographics brought the future to Ohio

First, a primer on early cable TV—which was developed in the post-WW2 era not to broaden channel choices, but to simply bring a signal to communities that were geographically shielded by terrain from receiving over-the-air broadcasts. Known then as Community Antenna Television (CATV), mining communities in Eastern Pennsylvania were among the first places to become wired. Eventually, small cable systems sprung up in most major cities, spurred by growing number of available channels that became available after the 1962 launch of the Telstar satellite.

Other possibilities for a wider array of viewing options included scrambled UHF channels, which required a set-top box to descramble (for a fee) channels beyond the usual local three, and massive C-Band satellite dishes,

In 1975, Warner Communications CEO Steve Ross was inspired by a closed-circuit television system in Tokyo’s Otani Hotel, developed by Pioneer Electronics. The system had some rudimentary interactive features, so Warner engaged Pioneer to develop the set-top box that would bring interactive television to a wider audience.

Warner owned a small cable system in Columbus, and set out to improve upon it with both a wider variety of programs, and with interactivity. Thus, QUBE was born.

Columbus, Ohio is frequently referred to as an ideal test market. With a demographic that closely mirrors that of much of the US, easy access via road or air from much of the country, and an educated population due to the numerous colleges and universities in the area, it’s a town that sees plenty of new ideas before they go national. After all, Compuserve, one of the pioneers of the pre-Web internet, was founded in Columbus.

Fast food restaurants, in particular, test many of their new wares in Central Ohio, as legendary New York Times columnist N.R. Kleinfield found three decades ago.

The heart of QUBE was the pairing of a console in each home with a studio-based computer that “polled” every box in the system every six seconds. In this manner, every viewer’s votes could be quickly tallied and reported. And QUBE gathered a massive quantity of personal data on each and every user in the system.

While Bruce Springsteen lamented his 57-channel idiot box, full of sound and fury signifying nothing in 1992, 30 stations was a revelation in 1977. Beyond the usual local network affiliates, independent stations from Cleveland, Indianapolis, and Cincinnati were beamed into QUBE homes.

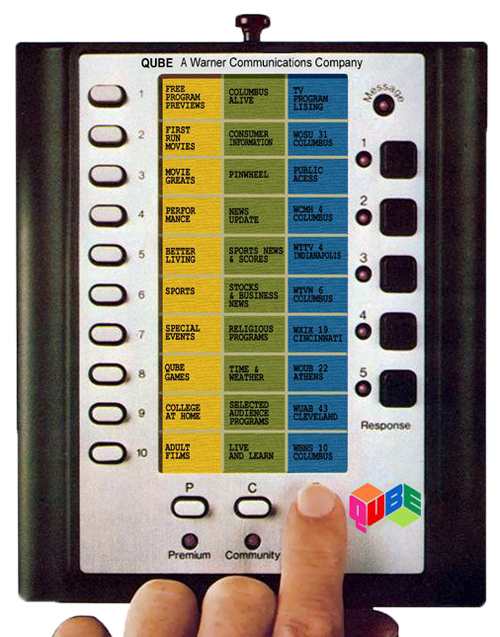

QUBE’s iconic remote.

Ten slots on the big wired remote control were dedicated to community-specific channels, including in-home shopping, music, children’s’ programming, and talk shows. Viewers could answer polls on local political issues, vote on an “American Idol” style talent show, or suggest what play the Ohio State football team should run next. No, the voting results weren’t passed to the coach, but it offered the joy of arguing in a sports bar from the comfort of a Barcalounger.

Another 10 channels were dedicated to “premium” programming, including pay-per-view boxing and adult films.

That adult channel is where privacy concerns begin to appear.

256kbps

The communication speed of the QUBE system—in 1977! While this would be considered slow even for a smartphone connection today, it was more than four times faster than the typical 56k modems that shipped with PCs in the late 1990s.

How deeper social questions still being asked today drove major concerns about QUBE

In any modern office environment, viewing pornography is rightfully considered sexual harassment, and is typically grounds for firing. In the early ’80s, however, Columbus mayor Tom Moody felt that watching QUBE’s adult movie channel was a critical part of his job.

“I do watch the adult channel in this office as part of my job,” Moody stated to refute an exaggerated report, “but to say it takes up 25 to 50 percent of my viewing time is grossly erroneous. I sample it every now and then to see what kinds of things are going on.”

Most certainly those QUBE computers knew how much the mayor was watching, but Warner-Amex wasn’t about to reveal individual data. In speaking with a former QUBE engineer, this writer learned that all consumer data was aggregated and stripped of personally-identifying information every night. Premium programming, of course, needed to be logged for billing purposes.

That data is what Columbus lawyer Laurence Sturtz was looking for when he subpoenaed Warner-Amex. Sturtz was defending the manager of a local adult movie theater who had been arrested on obscenity charges for showing an X-rated film—a film that had also been shown on QUBE. Sturtz hoped to show that, based on how many cable subscribers had watched the film, community obscenity standards and values weren’t being violated.

QUBE, after some legal wrangling, released the aggregate data rather than individual purchase information. Of 30,000 subscribers, 10,500 had paid to watch the film on QUBE. (No word on whether Mayor Moody was one of them.) Dominic Suriano, the theater manager, was acquitted of all charges on June 24, 1980.

Surprisingly, this service created serious ethical concerns for some.

Other concerns about interactive television were raised by political scientist and ethicist Jean Bethke Elshtain in a 1982 The Nation article. Her argument stemmed from the illusion of democracy given by the instantaneous polling made possible by QUBE. By asking for quick answers to complex issues—remember, QUBE communicated with individual homes every six seconds—reasoned responses to nuanced questions were generally impossible.

By asking viewers to vote quickly in the home, rather than sustain a traditional election campaign where options can be properly vetted, Elshtain felt that a plebiscitary system would overwhelm a true democracy. Plebiscitism, at least as defined in American politics, can be linked with populism—where a majority can overwhelm the views of the minority. That populism often leads to authoritarian rule. When Facebook was bombarded with populist messages in the runup to the 2016 presidential election, Elshtain’s concerns were validated.

QUBE may no longer be around, but many innovations developed in the QUBE studios are still making waves, as are many of the early employees.

Sight on Sound may have been a primitive form of MTV, but it didn’t look a lot like it.

Two early QUBE channels, Pinwheel (a children’s series) and Sight on Sound (a channel dedicated to concert videos and other music programming) eventually became cable stalwarts Nickelodeon and MTV, respectively. Warner-Amex sold off MTV and Nickelodeon, and shuttered the rest. Early QUBE employees included Steve Bornstein, who was an executive with both ESPN and NFL Network, Jim Jinkins, creator of the Nickelodeon series Doug, and Sue Steinberg, the first executive producer for MTV.

Ultimately, QUBE didn’t last. The high costs of generating unique programming, alongside maintaining an unusual infrastructure, doomed the experiment. $875 million dollars of debt in 1983 meant that QUBE couldn’t continue.

That doesn’t mean that other, similar systems didn’t reveal themselves. Anyone remember the Network Computer from Oracle?

Cable television, on the other hand, brought a virtual cornucopia of entertainment to households nationwide through the 80s, and many of those cable companies were the telecoms who later offered broadband internet (and thus social media) a decade or so later. One of those is now called Spectrum, the latest name of Warner Communications, which begat Warner-Amex, and eventually Time Warner Cable.

QUBE, while commercially a failure, showed consumers the potential for in-home entertainment and communication well beyond what one should expect from 1977—in both positive and negative ways.

:format(jpeg)/2018/06/tedium062618.gif)

/2018/06/tedium062618.gif)

/uploads/tonn.jpg)