Pens for Pennies

How cheap ballpoint pens, which are easy to lose and easy to make, changed the world due to their sheer disposability. They're really freaking cheap.

Tonight's GIF comes from a close-up of a ballpoint pen doing its thing, shot by the maniacs at NRK. Didn't know that Norwegian public television had it in them.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

“The strange thing is, I don’t remember buying any of them. They seem to follow me home from meetings, events, hotels, and conferences, and end up staying permanently. Judging from the number of disposable pens in every nook and cranny of my home, I suspect that some of them are reproducing when I’m not looking!”

— Fredrica Rudell, a retired professor from Iona College, discussing her pet peeve—the sheer number of disposable pens out there—in an essay on We Hate to Waste. Rudell’s piece cites a statistic from an EPA manual that 1.6 billion pens are thrown away every year—but that statistic, as straw fans might assume, is suspect. Not because a nine-year-old came up with it, but because the statistic dates back to at least 1986. A lot of stuff has happened since 1986, including the rise of the computer and smartphone.

The Bic Cristal pen, an icon of cheap pen design. (Wikimedia Commons)

The three individuals responsible for making the ballpoint pen so ubiquitous

The ballpoint pen’s creation story reminds you of the fact that it was once considered an exciting piece of technology.

Unlike the smartphone, which still shows glimmers of innovation despite being everywhere, the ballpoint pen has fallen into the tableau of everyday life, never really standing out unless you really spend time thinking about it.

But as an analog device, it solved a lot of problems, and it took a few tries to get right. The man to first patent the object, John J. Loud, did so about 60 years before the average person saw one in person, in part because the design was imperfect and it needed more work before it was ready for prime time.

Loud didn’t do any of that work, but in the years surrounding World War II, inventors and businessmen helped bring the ballpoint pen to the public eye and keeping it there. Key among those innovators:

Laszlo Biro, once a working journalist, realized that the ink commonly used on newspapers dried quickly and without smudging, unlike the state of affairs seen with fountain pens. This observation made him realize that pens could be greatly improved if they could use thicker ink than was common in fountain pens at the time.

Of course, fountain pens had a variety of issues that made their use at times frustrating. Among them: They had a tendency to leak; they needed to be constantly refilled; issues with the nib, or the metal tip of the pen, could cause problems such as a pen that tears the paper or makes it possible for the ink to hit the page at all; and fountain pens don’t tend to do well at high altitude, making them a bad bet for planes. (That last issue would prove fundamental for the pens’ early update.)

Teaming with his brother György, Biro came up with a ballpoint mechanism that would allow for a small amount of the thicker ink to flow onto a page at a time. The ink dried faster, and the storage of such ink was easier to manage due to its reliance on a physical phenomenon called capillary action, which slowly drew the ink out of the pen without the assistance of gravity. It was such a forward leap for ink that it was clear that such pens would eventually take over.

However, there was World War II to contend with, and the Biro brothers were caught in the crosshairs with their invention. Based in Budapest, the brothers were forced to flee the war zone due to the Nazi threat. The brothers soon moved to Argentina, then worked to commercialize their product. The ballpoint pen’s initial success hinged on its ability to perform at high altitudes, which made it the preferred writing instrument of both the British and American Air Forces. And after the war, the pens found quick success—though it should be noted that another entrepreneur beat them to the U.S. market.

From a Reynolds Pen ad in a 1946 issue of the Chicago Tribune.

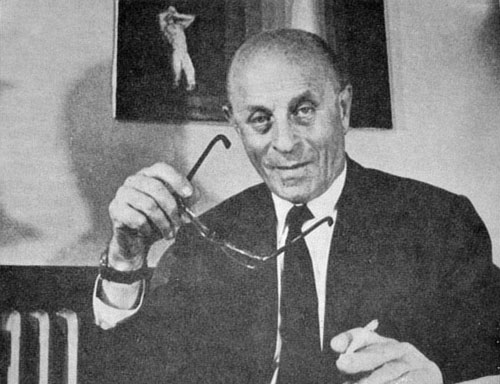

Milton Reynolds, an American entrepreneur who went through numerous periods of success and failure in his lifetime, saw the ballpoint pen, which hadn’t been introduced in the U.S. market, as something consumers would be quick to buy.

So he got moving, quickly cloning the idea. The ballpoint pen itself had fallen out of patent, but the method the Biro brothers used, specifically the way that it pulled ink out of a tube, had been freshly patented. So Reynolds came up with an alternate process that relied on gravity to push the ink through, rather than the use of capillary action.

This allowed Reynolds pens to succeed in the market first—because the technology was still new, and still innovative. In fact, it created a lot of competition within the market. One 1946 Associated Press piece describes a highly litigious competition around the pens, alternately going into discussions of antitrust violations and patent infringement. Whatever the case, the pens made everyone involved a lot of money. Despite a cost-prohibitive price tag of $12.50 ($173.07, with inflation added) according to a 1946 New York Times article, more than 5,000 people swarmed Gimbel’s department store on the day that the pens were first sold in October of 1945, and the ensuing competition and price war meant that millions were sold on the market in the first year.

Reynolds talked a big game, claiming that its pens would last four years. But the weaknesses of the early ballpoints—including a tendency to leak—gave fountain pens an opening to stick around for a while longer.

That made room for other companies to enter the market to properly sell the idea—including a company you’ve most certainly heard of.

(via the Bic website)

Marcel Bich, a French industrialist who had deep knowledge of the pen industry, bought out Biro’s patent in the early 1950s, a move that proved brilliant, because Bich’s company, Bic, was masterful at producing disposable devices at an incredibly low price point.

More than any other company or device, Bic’s Cristal pen came to define the pen as an easily replaceable commodity, meaning that if there was a problem with the pen you were using, it was simply easier to get a hold of another pen than it would be to fix the pen that wasn’t working.

Bich entered the American market through its acquisition of the Waterman Pen Company, and quickly overtook the market, thanks in no small part to its price—just 29 cents upon its launch, and rarely above that price point since. (In fact, if you buy them in a multi-pack, the average price is around 20 cents today.)

By the 1970s, the company had replicated the success of the disposable pen through a series of products that could be replicated just as cheaply, including the disposable lighter and the disposable razor.

Each of these businessmen played a distinct role in making the ballpoint pen famous. Laszlo Biro put the time into actually building the basic form of the pen; Milton Reynolds helped to create a market and buzz for ballpoint pens in the United States; and Marcel Bich found the model that would help turn ballpoint pens from a fascinating novelty into an easy-to-ditch commodity, helping ensure that even if the ballpoint wasn’t perfect, it would still be cheap enough that it wouldn’t actually matter.

1949

The year that the retractable pen was first introduced. The manufacturer, the Frawley Corporation, innovated in another way, by using ink that dried immediately. The result was that the pen, called the Paper-Mate and patented in the early 1950s, would become a massive success. The owner of the company at the time it introduced the retractable pens, Patrick J. Frawley, Jr., also was known for his ownership of the Schick razor brand—an ironic business move, considering that he sold Paper-Mate to Gillette.

Why pens are such an effective form of merchandising

The ballpoint pen’s eventual decline in value from novelty to commodity was a real shot in the arm for the promotional products industry, and likely a further driver of the pen’s eventual role as something that just shows up in your pocket without your ever realizing how it got there.

The industry around promotional products has been around longer than you think. One of its most iconic players that’s still around today, Quick Point, has been making pencils and pens since 1928, and the business has expanded from there. Per estimates from the Promotional Products Association International (PPAI), the largest industry trade group focused on so-called “swag,” its distributors sold an estimated $23.3 billion in goods in 2017.

At 6.6 percent of the pie, writing instruments make up the third-largest category for promotional goods, after wearables and drinkware, but on the other hand, wearables like T-shirts and bags generally tend to cost more to produce. When you can make a pen for just a few cents and you can get your logo printed on it for not much more than that, the value of that pen in getting a message across is fairly high, and the tactic used to spread that message often shares a lot in common with word-of-mouth or viral marketing strategies.

That’s because people don’t tend to use disposable pens once, but they also don’t tend to use them forever. And so many pens are accidentally distributed that it would be an impossible job to keep track of where every pen went.

Let me offer a couple examples of this basic point:

You’re at a restaurant, and you’ve paid for your meal with a credit card. You sign the check, but without thinking of it, you accidentally pocket the pen, which may or may not have a logo on it.

You go to a conference for work, and while you’re walking through the convention center, you see someone you met earlier at the conference and hand over your business card. You’re looking to meet up later, so you ask to borrow his pen to write down a time on the back of the card. After you get back to the hotel, you open your bag, and there it is: The guy’s pen.

You’re at the office, and you need to leave a coworker who’s not at their desk a note. You write something up on a Post-It note, grabbing the pen from the little pencil holder on the desk. Two weeks later, as you’re looking for something on your own desk, you realize you still have your coworker’s pen. However, the value of the pen is so low that it would cost more to have an awkward moment around the pen than it would to keep it without any issue.

In each of these cases, you’re technically guilty of stealing a pen, even if it was unintentional. But also in each of these cases, pens are plentiful; they won’t be missed. Conventions give away pens like candy, and both offices and dining establishments are known for their ample pennage.

But for a company whose logo is on the side of the pen, it’s a win for them, because they get their message shared with another person. And that’s a good thing from a marketing perspective. PPAI actually did a survey on the effectiveness of logos on pens in 2012, and found that name recognition of the logo brand on the side of the pen was high, with 70 percent of promotional pen users remembering the brand being promoted.

The pen’s exposure was both fairly high—with 40 percent consumers pulling out the pen up to five times per day, and roughly a third saying that the logo on the pen influenced whether they contacted the advertiser.

And promotional pens, overall, were also cost-effective: A single pen cost $1, but the impression cost of the pens per thousand users was around $0.46 over an entire year.

Sure, the pen may not be the loudest or even the most obvious marketing tool, but it gets the job done. (Whether it’ll keep working or run out of ink is another question entirely.)

100%

The percentage of people that have stolen a pen from a colleague, according to an oft-cited statistic by the pen manufacturer Paper-Mate. The study on office theft, which took place in 2011, found that when it happened, it was almost always accidental, with just 22 percent stating that they had done so consciously. Paper-Mate promoted this study in part to sell the public on the idea that the company sells the “World’s Most Stolen Pen,” the InkJoy, to which we say, yeah, whatever you have to tell yourself to defend your market share from Bic.

In a lot of ways, the ballpoint pen plays a role in the analog world not unlike that of the membrane keyboard. Sure, enthusiasts talks about their love of mechanical keys, but when it comes down to it, most people get their work done using cheap membrane keys.

Likewise, the ballpoint pen is ubiquitous, even though much of the enthusiast interest is really around fountain pens, nibs and all.

Even considering that, the ballpoint pen plays an important role in mainstream life, in ways good and bad. On the bad front, its sheer disposability, which was not a feature of the initial version of the product, allowed for sophisticated marketing of the device to consumers, but not exactly the best track record on the environmental front. It suffers from most of the same problems as straws, even though it gets little attention in comparison. (There is a recycling program for pens, however, run by TerraCycle.)

Most pens get thrown out or forgotten about long before they’re anywhere near their expiration date.

But on the plus side, the disposability of the pen served as a precursor for a lot of creativity in the ways that we sell and market products. Because pens are so cheap to produce, they don’t always need to be sold. A hotel or bank can just keep a bunch of branded pens lying around in a common area, and boom, they’ve just quietly created a bunch of word-of-mouth marketing for themselves.

One thing that’s always intrigued me is the fact that companies that sell razors and companies that sell pens are so intertwined with one another, despite the fact that the devices have little, functionally, in common.

The reason for their commonality, of course, is that the business models, especially in the wake of the disposable pen, are basically the same: They either get thrown away, or their cartridges are replaced.

If the computer is the greatest invention of the 20th century, the disposable ballpoint pen might not be too far behind. But unlike the computer, which is often most successful in its more advanced forms, the ballpoint pen is most impressive in its least-expensive variations.

It’s amazing that we can mass-produce so many pens at this price point.

--

Find this one a fascinating read? Share it with a pal! And thanks to our sponsor Knew Amsterdam.

:format(jpeg)/2018/08/tedium080218.gif)

/2018/08/tedium080218.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)