Clippy Couture

Clip art gets a bad rap as an artform, in part because it’s everywhere. Let’s give it some grudging respect by filling in some historic gaps.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

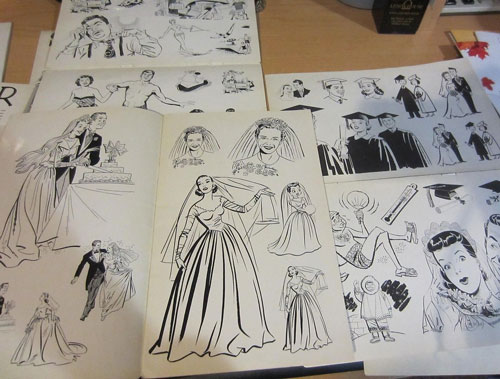

Examples of the Harry Volk clip book.

Clip art didn’t start with the computer, though it certainly thrived there

Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, a constant thread has pushed forth the business of publishing—a thread in which information constantly, and repeatedly, became both easier to access and easier to publish.

You can follow a thread from the printing press, to lithography, to the Xerox copy machine, to the dot-matrix printer, to early internet sites like GeoCities (and the webrings they spawned), to blogs, to social media.

And this, of course, created new business models that took advantage of these growing needs. Obviously, social networks like Twitter and content management systems like WordPress are the modern face of this kind of business necessitated by need, but plenty of examples of this existed beforehand.

One particularly notable example for which not a lot of information can be found online is that of a former journalist named Harry Volk, Jr., who became the founder of a namesake company that specialized in a specific kind of artform: The art of the generic.

Volk’s company, based in New Jersey and active for more than three decades, specialized in spot illustrations, essentially the kind of art that appears to give the page some color, perhaps based on the theme of the content. But the brilliant thing Volk did was sell the books to basically any publishing shop that needed one—because, as it turns out, not every newspaper or magazine has a New Yorker-size budget for illustration.

Finding information on Volk’s contribution to the rise of clip art is arduous at best—the best source about it is a 2008 blog post featuring quotes from Thomas B. Sawyer, best known for being the head writer on the iconic CBS show Murder, She Wrote, as he discusses his days doing illustrations for Volk, whose glossy books he described as “ubiquitous, a presence in the art departments of virtually every non-major ad agency, house-organ and art service in the U.S.”

Sawyer, who fittingly wrote a memoir titled The Adventures of the Real Tom Sawyer, said that Volk was his favorite client during his days as an illustrator, in part because Volk gave him a lot of freedom.

“I became his star illustrator, and because of the broad, even international exposure my drawings got, a lot more work came my way,” Sawyer wrote. “I cannot come close to counting the times over the next fifteen years that I’d open a magazine or newspaper, change TV channels, receive a pamphlet, or pass a signboard, and unexpectedly see one or more of my Volk drawings.”

(via Worthpoint)

Easier to find, however, are actual examples of the clip art. This is thanks, in part, to a guy named Bart Solenthaler, who has gathered up much of the vintage art in a collection he calls the Bart&Co. Historic Clip Art Collection, a portion of which can be seen on Flickr, it’s not all Volk, but much of it is, Solenthaler told the site Flashbak earlier this year. He explained that the art was nearly headed for the trash heap, but he decided to save it instead.

“I was employed by the New York Times Advertising Department at the time and was tasked with throwing the files into a trash dumpster,” he explained. “I asked if I could have the clip art rather than throwing it in the trash. And the rest, as they say, is history.”

Why would someone want to throw away all this beautiful art? The short version is that its value in its original context had declined. If you’ve dug around a lot of old books or magazines, you might find the style very familiar, if not the drawings themselves. An ink-based style that fits somewhere in-between the realism of a Normal Rockwell painting and the style of an era-appropriate comic book, the art shows up at a somewhat regular clip on eBay. (For example, in this order form.)

But, like most clip art, it dates itself. Despite arguably being of higher quality than most modern clip art (in part because of how it was used), you can tell that it was done in the 1950s or 1960s. That eventually became a major knock against it.

But the mechanisms of publishing were there to push the concept of clip art along. By the 1970s, the basic idea of clip art started to trickle from the ad agency to the bookstore. A major driver of this was a company named Dover Publications, which made its name by popularizing the trade paperback in the 1950s. The company became known for reprinting books full of text and images that had fallen into the public domain, such as images of iconic artwork. A 1980 review of a series of Dover art books, published in The Clarion-Ledger of Jackson, Mississippi, aptly nailed down the company’s approach: “Famous artists’ work collected on good paper at reasonable prices.”

In a lot of ways, Dover was applying the public domain resale approach used for movies to books—and doing well with it.

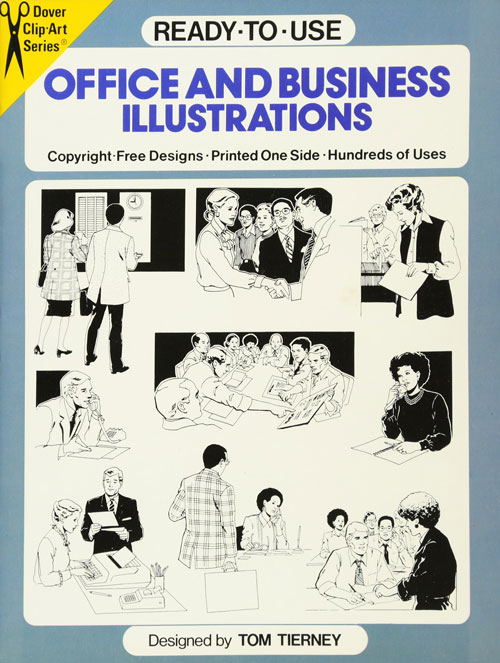

Because you never know when you need an office or business illustration.

It turned out that less-famous artists would also work well for Dover. It was simply, at the time, a smart model for a mainstream publisher to produce books of line art specifically for the purpose of being cut out and used elsewhere. It worked well for paste-ups and with copy machines, and the scrapbookers of the world could always use a new border or two.

So it only made sense that a company would specialize in mass-market books that did nothing but print clip art. Many of Dover’s titles, in big letters, proclaimed that there was no copyright on the art within the books. (These books are also easy to find on eBay.)

While Dover wasn’t alone on the clip-art market, its approach was perhaps the most common—which put the company in a good position, because these metal, boxy things called computers were turning clip art from a novelty to a game-changer.

$90

The cost, per disk, of buying clip art for the VCN ExecuVision, one of the earliest presentation programs on the market. (The presentation program itself cost $400, according to the Computer History Museum.) The software, released in 1983, is believed to be the first use of clip art in computers, predating the better-known Print Shop by about a year.

(via Brad Fregger’s website)

One of the earliest computer artists was responsible for some of the earliest computer clip art

Roughly 20 years before Joan Shogren played a key role in the creation of some of the earliest clip art, she was giving an IBM machine some artistic license.

As a secretary in the chemistry department at San Jose State University in the 1960s, Shogren helped put together the first public display of computer-generated art at the university’s bookstore. Shogren was credited with the basic idea, which involved creating a machine that would generate paintings based on mathematical equations input into the computer.

Brad Fregger, an early Activision employee who I highlighted in another story a while back, noted on his website last year that the experiment is believed to be the first attempt to publicly display computer-generated art. The notice the art display got led IBM to ask Shogren to create a display for its then-new office in San Jose, using the same approach.

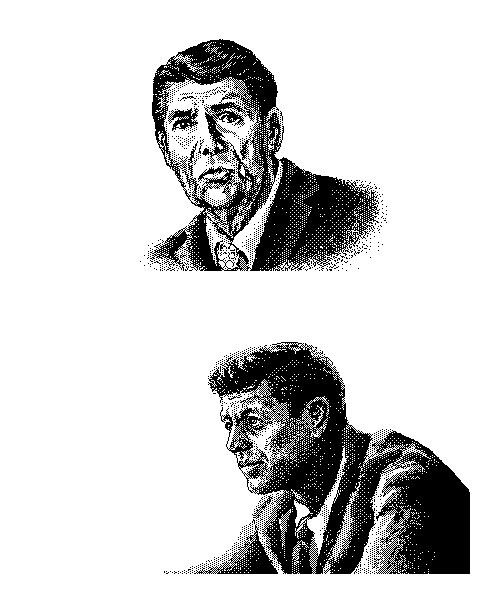

The initial variation of ClickArt featured images of multiple presidents. (via MacPaint.org)

Fregger’s brother, Dennis, along with their associate Mike Mathis, got a chance to work with Shogren a couple of decades later on a completely different kind of computer art project—the early Mac app ClickArt, one of the first dedicated pieces of software based around stock art. The software was perfect for the Macintosh, whose GUI was being highlighted with the help of MacPaint.

That said, while the idea was inventive, early reviews were not necessarily kind. In an August 1984 piece, InfoWorld reviewer Annie Cates strongly implied that ClickArt, as well as the competing Mc Pick, were novelties whose value didn’t match the $49 price tag—particularly because of issues with the packaging, which didn’t explain what the software did very well.

“In effect, the products are really Mac gimmicks,” she wrote. “If the images are useful for you, and you manage to pull them into your artwork, the products are OK—but they are not worth running to your local computer dealer to buy.”

But progress on clip art would quickly be made. A later review by Cassie Stahl of two other clip art tools, Mac the Knife and Art Portfolio, found that progress had been made between August and November of that year.

And it’s important to note that the desktop publishing revolution that gave the Mac a foothold in the office didn’t really hit full steam until the next year—and once that hit, it was clear that clip art would play an important role in our future.

Case in point? While McPic, Mac the Knife, and Art Portfolio (could the developers have picked three harder-to-Google names?!?) have fallen into the abyss of obscurity, ClickArt—the tool with a legacy that dates all the way back to the first computer art show—is still being produced in the present day by its current owner, Broderbund. (It’s a cloud service!)

The profit margin on this software was 90 percent.

Five ways that the computer clip art industry was surprisingly innovative

- It attached early to the cloud. Decades before it became common to subscribe to a networked service that relied on downloading data from the cloud, the company Adonis sold a service called Clip-Art Window Shopper, which you paid $35 per year to access, and then could use to download clip art images on the fly at prices ranging from $1 each to $18 each. (Hope you like that shot of a flower vase.) The Windows 3.0 app, which appears to not be anywhere online, reportedly won awards, which makes sense, because it beat Adobe’s Creative Cloud to the same idea by more than 20 years.

- It gave the CD-ROM a practical use. Sure, the early uses for the CD-ROM focused on things like encyclopedias, but the sheer amount of clip art out there made it a sheer natural for expanding storage. (It made more sense than the magazines, that’s for sure.) Evidence of CD-ROMs exists all the way back to the late ’80s, and companies like Dover (which, yes, made the leap to digital clip art) still sell clip art on optical discs.

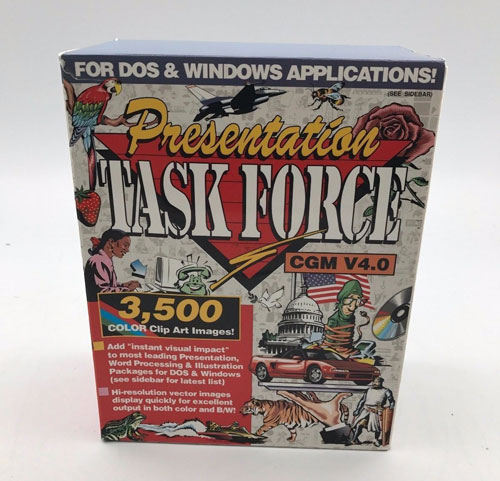

- It was early to vector graphics. Most people in the know about computer art know that vector graphics, which are based on line drawings, are more flexible and versatile than bitmap files, which tend to be used for photos. By the late ’80s, it was possible to get clip art in vector formats such as EPS and CGM.

- It wasn’t afraid to cut a deal. The company New Vision Technologies scored in a big way after agreeing to a deal with the software manufacturer Lotus in the early ’90s that put its clip art in the hands of millions of users. The company was a relatively tiny startup that took advantage of the sudden demand for good graphics to sell its popular Presentation Task Force, which cost $20 to make and sold for more than $200 a pop.

- It was ready for the rise of the animated GIF. In the late ’90s, the service Animation Factory came to life as a clip art site that focused on 3D animation. Later, those GIFs lent themselves to wonderful memes, particularly “dat boi.” The firm, which is still active today, sells some incredibly weird GIFs, and their story is all over the map. The podcast Reply All did a great episode on the service in 2016.

2014

The year Microsoft unceremoniously killed its clip art feature in Microsoft Office, due to a growing preference for using image search by users. The decision got a lot of notice at the time, even though, let’s face it, you probably weren’t even aware.

The strange thing about clip art, in its myriad forms, is that when you break it down, it’s a shortcut—a way for people who aren’t visually creative to express an idea simply without having to use a skill set they don’t have, or a way to save some time when that time is of the essence.

Its role has faded a bit since the ’90s, with stock photo services largely taking their place. The rise of digital photography and improved photo-editing capabilities meant that people looking for a shortcut had a wider pool of emotions and ideas to choose from.

It should be made clear, though, that a stock photo and a piece of clip art are not interchangeable. They represent two distinct forms of visual communication, and while those forms sometimes overlap, they serve different roles.

Clip art has a lineage with the cartoons you see in The New Yorker or elsewhere, and in many ways doesn’t get the respect it deserves. Case in point: Harry Volk, Jr.’s company deserves huge credit for defining a key aesthetic look of the 1950s and 1960s, yet information about him and his company is nearly impossible to come by. His company’s body of work represents a significant amount of cultural history, and The New York Times—a friggin’ font of archival materials on the editorial side—was going to throw it away!

I don’t understand it one bit. Is it possible that people of his day looked down on his company’s art the way we might scoff at a default graphic on a resume in 2018?

Clip art may be everywhere, but it’s still art. It deserves a grudging acceptance even if its goal has never been to set the world ablaze.

:format(jpeg)/2018/08/tedium083018.gif)

/2018/08/tedium083018.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)