Double Trouble

How a court battle involving groundbreaking disk-compression software foreshadowed Microsoft’s status as an antitrust darling.

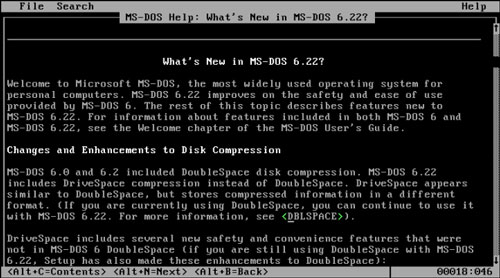

Today's GIF comes from an Italian clip of someone using DriveSpace—not DoubleSpace, DriveSpace. The distinction matters.

$1,200

The cost of a 40-megabyte Western Digital hard drive in 1989, according to a chart put together by software engineer Matthew Komorowski, who did in-depth tracking on the cost of purchasing a gigabyte of hard drive space, by year. (According to a 2014 update to the chart, it costs $0.03 to buy a gigabyte of storage; you can now buy a 4-terabyte external hard drive for $84, or 2.5 cents per gigabyte.)

The Stacker box, with its distinctive text-based design. (via Virtually Fun)

The company whose compression technology doubled your hard drive space

As any BBS user knows, file compression was a fundamental part of what made computing in the ‘80s and ‘90s manageable.

(Its success in that particular form is likely why the creation of Phil Katz’s popular PKZIP, one of the most popular file formats of all time, feels something like an arms race.)

But hitting its stride at right around the same time was disk compression, which attempted to take everything on a disk (usually a hard disk), remove repetition wherever possible, and bring it down to a smaller size.

During the early ‘90s, a time when fairly tiny hard drives cost about as much as many computers do nowadays, this technology was seen as a game changer, helping to maximize an incredibly scarce investment.

At the front of these efforts was a company called Stac Electronics. Formed in 1983, the firm spent years working on its compression technology, which threw both software and hardware at the problem of limited disk space. It took them a number of years to turn that compression technology into a consumer product—the firm applied for a series of patents during the late 1980s—but it proved worthwhile in the end.

At first, it seemed like Stac’s compression technology would end up mostly in hardware applications—say, directly embedded into tape backup drives. And this was certainly the case to some degree, with the Quarter Inch Committee (a group focused on the uptake of quarter-inch-wide computer tape drives) implementing Stac’s research into its QIC-122 data compression standard.

But as it turned out, the compression technology worked really well in software form, too. And, considering the cost of disk storage during this period, the potential upside of this product was extremely high.

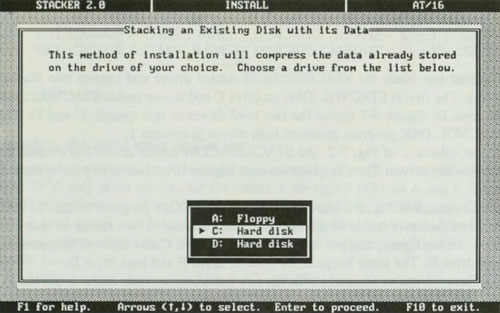

A screenshot of Stacker from the book Stacker: An Illustrated Tutorial.

At the time of its 1990 release, Stacker seemed like magic. It had the ability to compress the entire contents of your disks, only pulling out what you were using when necessary. Unlike PKZIP, it was able to compress and decompress files at will. You could even defrag your disk with everything compressed on it, something its main competitor at the time couldn’t do.

Dan Gookin, the author well known for originating the … For Dummies series of books, wrote an entire book about Stacker, a tool he raved about in the introduction.

“This program is incredible. I’m glad I have the opportunity to spout off about it for the next 176-or-so pages,” he wrote. “Few utilities impress me, so when I’m excited about something, it really shows.”

A Stacker coprocessor card, using the less-common MCA bus. (The Iron Album)

Part of what made Stacker an attractive option was that it was both a software tool and, if necessary, a hardware tool. Just as GPUs exist to offload graphics onto a coprocessor, users could upgrade Stacker with a hardware add-on that both improved the performance in some cases and increased the level of compression. The coprocessor card wasn’t necessary, however, though it was a definite benefit for some, as it helped to nullify the natural performance hit that came with a tool that compressed and decompressed files at will.

Perhaps it wasn’t perfect—there were little finicky issues here and there that could produce errors and data loss—but it was very impressive for its time, and effectively mitigated a significant problem.

Stacker made Stac Electronics a star—and it would only be a matter of time before a certain company would try to borrow some of that luster for itself.

1994

The year that Stac Electronics’ key compression technology, called Lempel–Ziv–Stac, or LZS, was accepted as a formal standard by ANSI. The compression technology combined two existing types of algorithms into a single approach. The first, called LZ77, was a “sliding window” technique developed by Abraham Lempel and Jacob Ziv in the ‘70s that compressed data by making repeated references to earlier mentions of that data; the second, known as Huffman coding, was developed in the 1950s and breaks down longer strings into a series of nodes on a binary tree. In other words, LZS compresses data in two different ways—first, by removing repetition, and then, by breaking it up into little pieces.

TFW your idea is stolen by the biggest tech company in the world (Wikimedia Commons)

When Microsoft swooped in, the deck was stacked against Stac

A technology as interesting as Stacker was bound to draw the attention of some major tech-industry players, and Microsoft was very much enamored with what Stac Electronics had built.

So much so that it made a version of its own.

When Microsoft was working on version 6.0 of its dominant operating system MS-DOS, the company reached out to Stac to see about adding Stacker to the operating system. According to a 1993 InfoWorld article that came out just before the operating system was released to the public, Stac officials claimed that Microsoft had come into negotiations with an aggressive stance, saying that if it didn’t license the software to Microsoft for free, the software giant would crush Stac.

Stac Chairman Gary Clow wouldn’t play ball.

“They are saying, ‘Give us your product or we’ll go to your competitor and put you out of business,’” Clow told InfoWorld. “This is tantamount to predatory pricing because what they have decided to do is get into the utilities market, and they are going to sell below cost.”

When a beta version of MS-DOS 6.0 arrived in Stac’s offices, it included a piece of software called DoubleSpace that effectively mimicked Stacker. Stac, which had patented its compression technology, quickly sued.

The legal action represented the first patent lawsuit in Microsoft’s history.

New or not, Stac’s lawsuit against Microsoft would prove to be a high point of the form. At one point, Microsoft played hardball, filing a countersuit against Stac that claimed the company’s patents were invalid. Which seems like a stretch until you consider the fact that patent battles involving computer software were relatively untested in federal courts at the time.

Meanwhile, DoubleSpace proved to be providing double the headaches for Microsoft. Reports of disk corruption issues were widespread (especially when using the other main new feature of MS-DOS 6.0, ScanDisk), and the software raised a number of concerns among users, who wondered, as PC Magazine put it in November of 1993, “Is It Safe?”

Utility makers took advantage of the consumer concern, suggesting that Microsoft’s compression tool was fundamentally flawed. The very technology that just three years earlier, under a different firm, was seen as groundbreaking, suddenly looked dangerous and flaky under a different corporate parent.

And the headaches wouldn’t end there for Microsoft. Stac’s lawsuit quickly gained momentum in the courtroom, and a jury sided with David, rather than Goliath.

Embarrassingly, Microsoft had to release a version of MS-DOS, version 6.21, that did nothing but effectively delete the DoubleSpace software from computers.

Microsoft, looking to settle, ended up paying Stac money and buying a stake in the firm, all so it could bring back the marquee feature of MS-DOS 6.0—which it did, under the name DriveSpace.

That version of MS-DOS, version 6.22, would prove to be the last version of the famed operating system that was released to retail.

The win would provide fodder for a deeper debate. In a 1994 article, The New York Times noted that the lawsuit was seen as an early harbinger of the reach of software patents, which were still fairly new at the time of the judgment:

The decision involving Microsoft's MS-DOS 6.0 software, the operating system under which application programs run, is likely to fuel a controversy about whether the nation's patent process is appropriate for the rapidly changing software industry. The Patents and Trademark Office, which began issuing software patents only a decade ago, has been accused of having inadequate expertise in software to judge what is truly novel.

(These debates, of course, continue to this day; see all the hubbub about patent trolls.)

What's new? More like what's embarrassing.

Microsoft’s DoubleSpace gaffe was a harbinger of legal battles to come

Ultimately, the patent lawsuit said more about Microsoft, and where it was going as a company, than it did about Stac Electronics.

Sure, the company had previously been accused of stealing the “look and feel” of the Apple Macintosh for Windows, but this was different; it had effectively gone through a negotiation process with another company, only to watch it fall through their hands, then decided to respond by coming up with a competing technology to give away, only to have a jury put the company in its place.

At this time of the ruling, the company had already drawn regulatory interest from the Federal Trade Commission, and the Department of Justice investigation into Microsoft’s domination of the PC software market was just getting going.

Months after Stac’s win in court, an agreement with the DOJ barred Microsoft from bundling products with its operating systems, though it could improve the operating systems with additional features.

Soon, though, a piece of software came along that was so attractive that the folks in Redmond couldn’t avoid copying it. Much like DoubleSpace a few years prior, Internet Explorer was a program integrated into a Microsoft operating system whose main competitor, an innovative startup named Netscape, was sold in stores in a shrink-wrapped form.

Microsoft, unfashionably late to the internet, called IE a feature of Windows 95, not a product. The Department of Justice disagreed with that sentiment. (This led to a much-discussed conflict that you can read about in great detail over here.)

The web browser, of course, became a part of the fabric of our digital lives, but what about drive compression software? Well, as hard drives quickly grew in space and fell in price, the technique fell out of favor. By the time of Windows 95’s release, gigabyte-sized hard drives were already established on the market, and their prices were falling almost as fast as the market was growing. Why compress your disk when you could buy a hard drive that was 50 times the size of the one you bought six years prior?

All of this meant that Stac Electronics, even after some business diversification, wasn’t long for this world. By the late ‘90s, the company had split in two, with its hardware business (and patents) going to a spinoff named Hifn, and its software business being renamed Previo. Neither business is with us in its original form today.

Of course, even if the players don’t live on, the math still works on those algorithms.

And while we’re not in a position where we have to literally double the space of our hard drives anymore, the spirit of Stacker very much lives on in a number of ways.

(ulleo/Pixabay)

For example, the open-source gzip compression tool, created in the early ‘90s, also combines Abraham Lempel and Jacob Ziv’s repetition technique with Huffman coding. This technique, essentially the Stacker concept in a file format, is now extremely common on most websites you use as a way of shrinking down the amount of data they use and limiting load times. Every website that uses gzip is kinda like a little Stacker unto itself.

Likewise, virtual memory—the idea of offering your computer’s RAM a backup on your hard drive—has benefited greatly from Stac Electronics’ work. In the late ‘90s, upon the release of Windows 95, “RAM doublers,” which effectively combined virtual memory with compression, became a popular kind of utility to for getting the most out of your machine, and one tool of this nature, Helix Software’s Hurricane 2.0, licensed the Stac LZS algorithm.

Later software further improved on virtual memory compression and moved to even better lossless compression algorithms (sometimes, as in the case of macOS, baked directly into the operating system), but LZS was a key stepping stone.

Heck, Microsoft itself uses some impressive voodoo to keep Windows 10’s footprint minimal on your machine.

In its original form, this algorithm impressed the hell out of people. One of those people was legendary technology columnist Walt Mossberg, who highlighted Stacker in his very first tech column for the Wall Street Journal in 1991, a roundup of software tools under $100 that he recommended.

“The process is complex, but you don't have to understand it,” he wrote. “The installation program guides you step by step.”

Maybe we don’t use Stacker in its original form, but its spirit—of the program that does something complex but impressive, while making it look easy—remains alive to this day.

That was one thing Microsoft couldn’t kill.

:format(jpeg)/2018/09/tedium090418.gif)

/2018/09/tedium090418.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)