Giving Candy A Bad Name

The surprisingly true story of Ayds, a diet suppressant candy that was incredibly successful until its name became forever associated with something else.

Editor's Note: Part of the reason I decided to do this story was because whenever I've seen this topic mentioned online, it's always seemed to be for the purpose of a dark joke, and that made me uncomfortable. For those curious, I played it straight here, because there are some deeper issues worth discussing about this topic—and not just limited to its name.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

Hedy Lamarr, in an ad for Ayds dating to 1953.

Before Ayds gained some brand baggage, it was a diet suppressant marketed by movie stars

When the candy Ayds was first introduced onto the market in the late 1930s, it was a clever twist for a model of advertising that was already gaining a lot of momentum: The ads that claimed to offer ways to help you lose weight and keep it off.

This is a common advertising trope even today of course, but back then, ad standards were a bit looser, allowing for slightly wilder claims. Case in point: A popular magazine ad campaign in the 1930s showed a drawing of a thin person, with a shadow of a much heavier person directly behind them—the message being that without taking the right level of care, you could fall off the wagon at any time.

The advertiser? The cigarette brand Lucky Strike, of course. “Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet” is a slogan that doesn’t sound so hot in retrospect.

Fad diets were already pretty common during the Depression era—the Grapefruit Diet came to life around this time, and there is evidence that there was a bread diet—a friggin’ diet built around bread—being advertised in the late 1930s.

Ayds played into this general tendency—and stood out because of its novel pitch: Eat candy, feel less hungry, eventually lose weight.

Early ads for the appetite suppressant leaned heavily on language that implied the medicine was something of a miracle worker. An example of the kind of language that promoted Ayds in newspapers around the country, circa 1940:

Ayds Candy contains NO DRUGS—No harmful Ingredients—$1,000 Purity Guarantee. We invite analysis. Ayds plan calls for no exercising. Many simply eat this delicious candy to curb their appetites for rich, fattening foods. Ayds plan is effective only in cases of overweight due to overindulgence in eating, which includes most overweight people. Ayds Candy helps supply Vitamins A, B1, and D to prevent deficiencies that might occur due to lessened appetite. Also contains valuable food factors from egg yolk, milk, maltose and selected vegetables. Only 7¢ a day—30 day supply for only $2.

Some of the earliest Ayds ads earned scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission due to their claims. One example of this, from 1942, includes the claim “100 Fat Ladies Lose 20 Lbs. Each,” and states that in a 30-day period, 100 people studied in a clinical test lost an average of 20 pounds.

In 1945, the FTC told its manufacturer, Carlay, to knock it off.

“In connection with the sale of ‘Ayds,’ a so- called weight-reducing product which the Commission found was nothing more than caramel candy enriched with certain vitamins and minerals, the respondents were ordered to cease disseminating any advertisement which represents that excess weight may be removed through use of the product in conjunction with the respondents’ weight-reducing plan without the necessity of restricting the diet,” the FTC stated in its 1945 annual report.

Of course, advertisers had other tricks up their sleeve. As Ad Age notes, Ayds was an innovator in the diet advertising realm, especially after World War II. During the 1940s and 1950s, the candy was frequently advertised in print ads featuring major stars of the day such as Hedy Lamarr and Zsa Zsa Gabor. The brand was on the up and up around this time, as its parent company was acquired by Campana Corp.

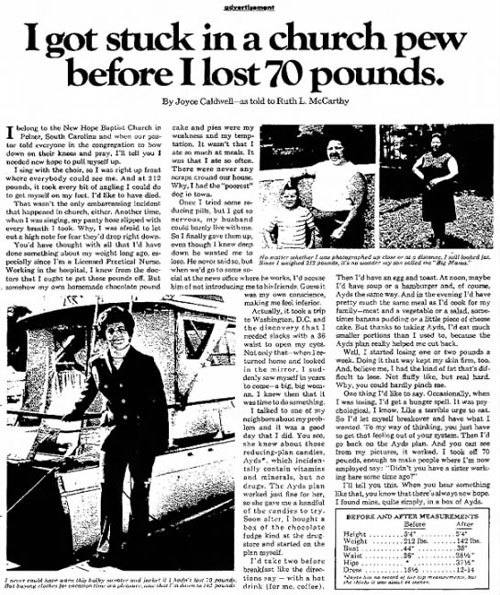

But by the 1970s, the strategy had gained a whole new level of sophistication, when full-page advertorial articles were published in newspapers with headlines such as “I got stuck in a church pew before I lost 70 pounds.” It was literally clickbait with nowhere to put your cursor.

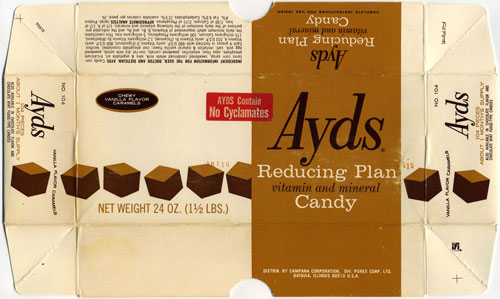

An Ayds box, from the 1960s or 1970s, prior to its reformulation. (Jason Liebig/Flickr)

Ayds, while a successful product, was not a perfect product by any means—its biggest period of success in the ‘70s and early ‘80s was at a time when serious questions about diet drugs, and the way they were being marketed, were being asked. And despite those claims from the ‘40s that Ayds contained no drugs (confirmed by looking at the ingredient list on this box), it did later use common chemicals for diet suppression in a reformulation.

Most over-the-counter diet medications of the era used one of two drugs: Phenylpropanolamine, which at the time was often used in cold medicine; and benzocaine, a drug known for its numbing effects that is often used in cough drops or Chloraseptic. By the early 1980s, Ayds candies used benzocaine to numb the tongue in an effort to ease the effect of taste buds, while other products in the then-expanded Ayds line used phenylpropanolamine, a chemical that is now banned in much of the world but was common then. (The FDA also attempted to ban benzocaine for use in diet medications, but the effort never got past the proposal stage.)

By the time phenylpropanolamine had been banned in the U.S., Ayds had already long exited the market. I’m not spoiling anything for you when I point out that you already know why.

1972

The year the Food and Drug Administration began evaluating over-the-counter drugs for reasons of safety and effectiveness. An FDA review of diet medications in 1979 found that phenylpropanolamine “may help people lose weight effectively,” a ruling that helped the appetite suppressant market explode in interest around this time; however, some medications were taken off the market because it was found that they contained too much phenylpropanolamine, which was considered a health risk. One drug that was banned for this reason was the diet pill Ayds AM/PM.

An advertisement for Ayds from the 1980s.

The brand conundrum that proved Ayds’ downfall

It was sheer happenstance that, in 1981, led medical officials at the Centers for Disease Control to give the name AIDS to the then-poorly-understood deadly immune system infection that was quickly spreading in the U.S. and beyond and was already in full-on crisis mode by the time officials came up with the name.

Robert Alden, a CDC spokesperson, denied to the Philadelphia Daily News in 1983 that there was any intention of intentionally giving the disease a snappy name, that the name was chosen because “acquired immune deficiency syndrome” matched the primary medical symptoms of the disease.

There probably wasn’t even much of a consideration of the side effects the name would have—and let’s face it, with a public health crisis of this nature, it probably was near the bottom of the list of considerations. People were dying, there was no cure, and the medical field was trying to act, fast.

Nonetheless, the disease’s name wasn’t exactly ideal for the makers of a certain diet suppressant drug. It didn’t matter that Ayds was first to the name with only a slight difference in spelling, nor did it matter that the candy had been on the market for more than 40 years at the time and was near its market peak. Ayds was no longer a brand name that was fully in control of its owner.

Even considering that, the owners of the brand at the time, Jeffrey Martin, put on a strong face, deciding not to initially rebrand despite the clear marketing challenge that was created.

“The only calls we have gotten on this thing have been from reporters,” company spokesman William McGuire claimed to the Daily News. “Frankly, I think the public is a lot more discerning than you guys. I think the distinctive spelling of our product in print and television has prevented any unsavory connection between the product and the disease.”

The company, however, faced headwinds that would soon prove difficult to ignore. While the company had been riding high in the late ‘70s on the back of the smoker-targeting whitening toothpaste Topol, many of its brands, including Ayds, had lost momentum in the market, and in fiscal 1986, its operating profit had fallen nearly 90 percent from its position in 1980. There were other factors at play for the company’s decline—the level of competition for over-the-counter drugs and other health and beauty aids had increased significantly—but it certainly didn’t help that it lost control of one of its most prominent brand names. Soon, the company would sell to Dep, a company best known for its namesake hair gel, for $75 million.

Dep, of course, realized that Jeffrey Martin had allowed some significant branding problems to grow under its ownership, and the company was looking to make fixes, not only to Ayds, but to everything else. In 1987, The Los Angeles Times put the dichotomy between the two approaches as such:

Seventeen months ago, the AIDS epidemic wasn't enough to convince the previous owner to change the name. Let the disease change its name, a Jeffrey Martin Inc. official said at the time. But today, the new owner acknowledges that it may be time to rethink the marketing strategy for Ayds, and yes, reconsider the name.

If watching advertising for the diet-suppression pills makes it clear in 2018 that the name had to go, the L.A. Times article at least suggests it was a matter of healthy debate among branding experts of the era, who felt that the name was well-known, even if it had gained a negative association. It still had a base of users that hadn’t gone away, even with the branding problem—it was just struggling to bring in new ones.

But by 1988, the decision became even more clear: Sales of Ayds had fallen by half, and Dep was already testing new brand names for the product according to a New York Times piece.

Eventually, the company decided to change the name to “Diet Ayds”—allowing it to keep the hallmark of the old name while distancing it from the disease.

But in the end, the decision wasn’t enough to save it. Diet suppressant candies, such as the MealEnders lozenges, are still sold today, but you won’t have any luck finding the product that originated this idea.

“I loathed [it]. I had romantic visions of artists’ garrets—though I didn’t fancy starving. Their main product was Ayds slimming biscuits, and I also remember lots of felt-tip drawings and pasteups of bloody raincoats. And in the evening I dodged from one dodgy rock band to another.”

— David Bowie, discussing his time as a commercial artist in the 1960s in the 2011 biography David Bowie: Starman. Yes, before Bowie became a rock star, he was designing ads for Ayds in the UK.

Branding issues of this nature are hardly limited to candies with unfortunate names, of course: Notably, around the time that Ayds was running into brand-association issues, Colgate was trying to sell frozen dinners, a move that didn’t work because the brand name had long been associated with toothpaste (even though the company had started out as a soap-maker).

But the thing that makes the tale of Ayds so fascinating is that it’s a situation where its ownership was so clearly crippled by indecision in response to the crisis. Unlike ISIS Wallet, Ayds had been around long enough that people would specifically look for that brand name in stores. ISIS Wallet failed in large part because of the brand crisis, but it was at least at the point where it hadn’t caused any real damage because few consumers had actually used the product.

Ayds was established, creating this complicated bit of game theory: Do they risk that existing audience and rebrand? Do they ride it out, on the off-chance that the CDC considers another name change for this deadly disease, full of unknowns? Or do they just write the entire product line off? No solution is good, but every solution is possible.

If you were the head of a company that suddenly found one of its most popular products had a branding problem of this nature, what would you do?

The answer seems simple now: get out of the way of a tragic public health crisis. But the answer wasn't simple then.

:format(jpeg)/2018/09/tedium092018.gif)

/2018/09/tedium092018.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)