The Lazarus Libraries

What happens when “lost” films and television shows become found once again—and what that does to the work’s cultural legacy.

Hey all, Ernie here with a piece from Andrew Egan, who is following his recent interest in film in a couple of new directions this time around. Check out what he found.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

2,749

The number of silent-era American films that are considered complete, according to the U.S. Library of Congress (LOC), the government entity tasked with preserving the country’s cultural legacy. This number only represents about 25 percent of all films produced from that era. A much smaller number of those films, about 11 percent, exist in their original release. Championing the preservation of early films has been spearheaded by big-time directors like Martin Scorcese and Quentin Tarantino. Understanding how these films were lost in the first place should help us better preserve the massive influx of intellectual property being created today.

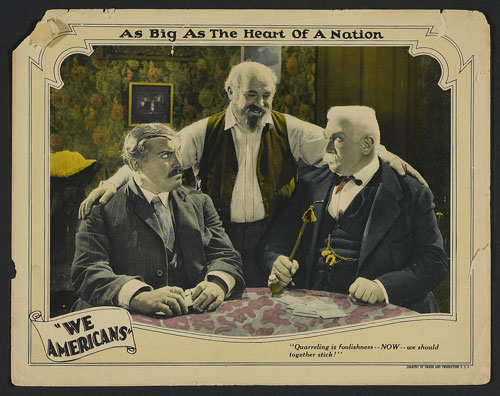

A card for “We Americans,” a Universal Studios film believed lost due to neglect.

A devastating fire in a vault

With hindsight, it is completely understandable why we lost so many early films. The medium was so new and abstract at its inception that no one really knew what they were doing. Even brilliant performers and producers whose legacies resonate into modern day, like Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin, were guilty of short-sightedness with their own work. But due to the notoriety of these performers, much of their lost work has seen been rediscovered.

Lesser known but historically significant films often didn’t receive the same treatment. The LOC noted that it was common practice for movie studios to destroy the negatives of many silent films. One of the most notorious offenders in this regard was Universal. By 1948, the studio had either deliberately destroyed or neglected all of their silent film negatives, including one gem that’s believed to be lost forever.

We Americans was a 1928 silent film telling the interwoven tales of three immigrant families moving to the United States. The filmmaker had complete cooperation from the government and even documented the actual immigration and customs process at Ellis Island.

“It is a tragedy that Universal allowed their silent films to rot or burn,” wrote film historian Kevin Brownlow in his book Behind the Mask of Innocence, a book on the silent film era. “We Americans would today be of immense historical importance.”

One studio did realize the importance of preserving their film archive. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, better known as MGM (of roaring lion fame), began earnest efforts in the 1930s to preserve their movies. Because the film stock used during the silent era involved combustible nitrates, the studio wisely decided to house their dangerous archive in a concrete vault on their studio lot in Culver City, California. With minimal ventilation. And no sprinkler system. You can see where this is going.

London After Midnight, a film that was widely believed to have been lost in a 1965 MGM vault fire.

Information is scarce—little was reported about it at the time, in contrast to a 1967 set fire that was larger in scale—but a 1965 MGM vault fire reportedly killed one person and wiped out the studio’s entire silent film archive.

“Someone was killed in that explosion,” film executive Roger Mayer told film historian David Pierce of the saga in a 1997 article for the academic journal Film History. “Somebody was working on the film at the time and as far as anybody could tell, it was an electrical short of some sort igniting the film.”

For what it’s worth, studio executives don’t think a sprinkler system would have saved any of the archive due to the volatile nature of the nitrate film. And this is how, through accident and neglect, we’ve lost around 75 percent of films made before 1929.

97

The number of episodes from the first six seasons of Doctor Who that are considered missing. This represents 38 percent of the show’s original run. Interestingly enough, Doctor Who fans recorded their own audio of each of the missing episodes during their original broadcasts so some they do kind of exist in one form or another.

(igorovsyannykov/Pixabay)

A lack of storage basically explains how we’ve lost things since the 1950s

During the 1970s, the British Broadcasting Corporation had a problem. In their mind, it was easily solved.

Through a combination of factors, the BBC found it’s vault overflowing with copies of things it couldn’t or wouldn’t air. (In some instances, the broadcast rights had expired, others were just old black and white movies or considered unprofitable or unsuitable for broadcast. The exact reason shifts from case to case. There’s also the issue with British actors union and a whole lot more. Detailing how the BBC handled its archive could be its own book.) So they started throwing things out or reusing materials for things they did want to keep.

The consequences of that decision were pretty widespread. At least enough to inspire MissingEpisodes.com (though its URL is definitely not MissingEpisodes.com), a website dedicated to detailing and finding lost British broadcasts. The site lists 92 British TV shows from the era that are missing episodes. Dedicated fans and collectors are often the ones to unearth copies of lost episodes, many of which were copies distributed to foreign broadcasters.

The same issues plaguing the BBC also hit NASA and a number of major film producers. As it turns out, no one was particularly good at preserving film until digital technology made film archives affordable and manageable. In America, TV shows and films made after 1970 largely remain intact. When an episode or film becomes “lost”, it’s usually a decision by the studio or producers to keep the end product out of circulation.

And this brings us to the strange cult status around a mediocre made-for-TV movie that aired once in 2001 before disappearing for a decade.

“In the 14 years we’ve been doing South Park we have never done a show that we couldn’t stand behind. We delivered our version of the show to Comedy Central, and they made a determination to alter the episode.”

— The statement from Trey Parker and Matt Stone about the altered version of their controversial 200th episode, which was supposed to feature a depiction of the prophet Muhammad, something of a no-no for the Islamic faith. Incidents like this aren’t uncommon and illustrate the strange relationship creators have with the corporations that ultimately present their work.

Why would Nickelodeon be afraid of a made-for-TV kids movie starring Frank Langella?

On Wednesday, August 11th, 2011, the internet did its magic.

On Reddit, a user posted a seemingly innocuous tidbit in the r/TodayILearned subreddit about a movie that aired just once on Nickelodeon in 2001. It was considered too scary for Nick’s core audience and shelved. No copies had ever been released and none had leaked to torrent or video sharing sites. Then a little over four and a half hours later, another user chimes in with a simple response, “I have a copy of Cry Baby Lane on VHS.”

The user wasn’t joking.

After going through the surprisingly complicated process of converting VHS to a digital format, interested millennials found themselves watching a lost memory.

By October, it was reported that the online interest in Cry Baby Lane had encouraged Nick and its owners at Viacom to resurrect the movie for broadcast on Halloween.

Eleven years and three days after airing, Cry Baby Lane finally got another shot at its intended audience. And the reviews?

Underwhelming to say the least. It’s a movie made for kids. In fact, many online wondered why Nick even bothered banning it in the first place. A rep for Nick said the movie was never formally banned, just forgotten. Online, most of the speculation on why has to due with the movie’s subject matter. The horror in the movie is focused on an ashamed father of conjoined twins. Eventually, he saws them apart. The larger plot actually resembles an episode of The Simpsons’ annual Treehouse of Horror entries with Bart having had a long lost, and more evil, twin.

Nick airs Cry Baby Lane from time to time. With the mystique gone, many threads on Cry Baby Lane include warnings to others to save themselves the hour and watch something else. Versions online run at a little more than an hour. When Nick runs Cry Baby Lane, they run it in a two-hour time block that includes damn near 50 minutes of commercials. That’s an almost criminal ratio of content to advertising, which leads me to suspect that might have been the ultimate deciding factor. It just wasn’t good enough to keep kids’ attention for that amount of advertising. Plus, you know, Langella don’t come cheap.

There are a lot of maxims, idioms, and turns of phrase advising what we should do with our history. Who knows what we should do with it? But it can’t hurt to at least keep it around. For offensive things, maybe not in public. Having our history available to anyone wanting or willing to study it is probably a good thing, overall.

When pieces of history, however seemingly inconsequential, are lost or censored or just limited in circulation, they can gain a power greater than its quality. The lost ideas of great, gone civilizations are tantalizing because we don’t know what they are. In that absence, we fill in the blanks of what it could be or what it could mean.

Lost films and TV shows do the same thing, though with admittedly lesser importance. When a lost Keaton or Chaplin film is rediscovered, it adds to our understanding of media at a specific moment. Cry Baby Lane does too but not in the same way. Its quality is almost irrelevant. (Though not when you’re trying to get through the damn thing.) What this simple, stupid made-for-TV movie managed to accomplish is something unique to the internet era. As long as no one forgets, it can almost always be found.

:format(jpeg)/2018/10/tedium101118.gif)

/2018/10/tedium101118.gif)

/uploads/andrew_egan.jpg)