Another Year of Tedium

The state of our Tedium in 2019 is a pivotal one if you love the idea of creating things online. Let’s talk about why—and what we can do to keep it safe.

Editor’s note: For those playing at home, here’s what we wrote ahead of prior years—2018, 2017, 2016, and 2015.

More oat milk than the average person will ever see in one place. (Tiia Monto/Wikimedia Commons)

Five signs 2019 will be better than 2018

- There’s an oat milk shortage, leading to massive price increases at a time when cheese is facing one of its largest ever surpluses. (You can currently buy a single liter of oat milk for $46 on Amazon.) But odds are it might actually end sometime soon as the 500-pound gorilla in the vegan milk game, Silk, gets in on the oaty action. If your company produces oat milk and would like to ship me a gigantic crate that I can then give away to my readers, we can make it happen.

- If you’re a child who lives in the state of Arizona, you’re getting a little more time outside of the classroom. The state’s governor, Doug Ducey, signed a law going into effect next year that requires elementary school students get two periods of recess per day, which should help the kids get over their budding Fortnite addiction.

- Macaulay Culkin, who made an impressive run during the last month of 2018 as my new favorite celebrity, is about to change his middle name to Macaulay Culkin. Which means his full legal name will be Macaulay Macaulay Culkin Culkin. Sometimes heroes are former child stars with great senses of humor.

- If you’re sick of talking about plastic straws, and would instead prefer to talk about other kinds of straws, I have some great news for you: One of the hottest fashion trends going into 2019 is the oversized straw hat. It’s not only fashionable, but it probably doubles as a flower vase in a pinch. I do all my writing while wearing an oversized Instagram-ready straw hat.

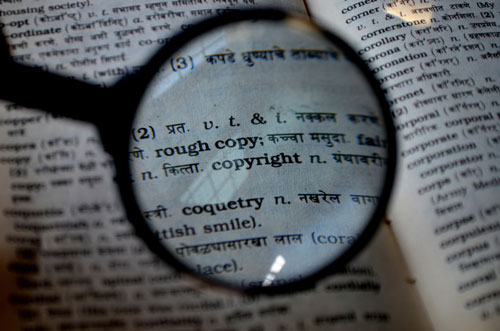

- The public domain is going to expand for the first time in more than 20 years, when works produced in 1923 enter the public domain, after we got through the whole calendar year without Disney trying to push for a new law to extend the term of copyright once again.

(via Pxhere)

The state of our Tedium in 2019 is defined by the messed up state of copyright law

As we finish out our year in Tedium, it’s becoming quite clear that we’re about to see some dangerous headwinds in the way copyright presses its rough imprint on the internet, and if you care about digital culture, you should be aware of what it means going forward.

But before we go too far forward, let’s go back a little bit, to something that happened around this time 20 years ago. In late 1998, the Recording Industry Association of America was in the midst of a lawsuit battle against the tech manufacturer Diamond, which had produced the first popular MP3 player, the Rio. The industry, years prior, put much lobbying effort into attempting to prevent a device like this from ever getting sold, having played a key role in the passage of a law called the Audio Home Recording Act of 1992, which aimed to prevent the sale of digital recording devices without built-in copyright protection.

The problem was, the legislation had a gigantic gap buried inside that the music industry hadn’t considered: The idea that digital music players would be used to copy digital music files, rather than direct audio from a source like a radio. As the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled in June of 1999, the music industry’s hard work was all for naught—and as it is, they were going after the wrong culprit, anyway—the digital music player, along with its successor the smartphone, would ultimately save the music industry, not kill it.

Around this same time two decades ago, Shawn Fanning was in his Northeastern University dorm room, drinking with his buddies, landing on the formative idea for the file-sharing tool Napster, which came about after said buddies complained about broken MP3 links online. He would soon drop out of school to program this app full-time. (Side note: He willingly gave up full-fat ethernet? In early 1999? Oh man.)

This tool, as I wrote earlier this year, forced the music industry to move away from lazy money-grabbing tactics such as albums with a single good song and a whole lot of filler. And on balance, it was good for the music industry, despite some fallow years, as it gave them platforms like Spotify and Apple Music.

But as 2019 begins, big content is getting more savvy in how it sells its attacks on digital culture to lawmakers—even if it remains blissfully unaware (or at least unappreciative) of its side effects.

As I highlighted in my recent piece about digital content filters, the European Union is uncomfortably close to pushing through some major copyright restrictions that could forever change the shape of the internet, by requiring the use of copyright-tracking filters on major social networks and distribution platforms and implementing regulations specifically targeting aggregators. The public is not clamoring for these things; this is a push by big publishers and big content creation companies to put more control over the way that we share their work.

But in a world where the public domain went dry for two decades, I worry about whether the next target the movie and music industries will go after is the public square, where discussion and commentary take place whether content providers like that discussion or not—or whether they’re even aware of the impact of the side effects of their work.

YouTube, a site that gained popularity off of illegally uploaded clips of Comedy Central shows and a central point of modern remix culture, is a perfect example of why the European Union should just leave well enough alone on copyright. Despite Google having the most savvy copyright-detection system in the industry, one that seems perfectly designed for the EU’s Article 13, edge cases are all over the place and universally handled in a way that favors complainants over creators, even in cases where it’s obvious creators are getting screwed.

Recently, I’ve been following the saga of the electronic musician Christian “TheFatRat” Buettner, who publicly called out YouTube for failing to properly mediate copyright disputes that it created, leading to a situation where a company without any active social media profiles was able to claim ownership of his original song without any proof it was actually theirs.

Buettner, prior to this incident, has been the kind of creator worthy of emulating online. He allows his fans to share and remix his music for free, so long as they don’t claim ownership as this random company did. And with his digital voice as prominent as it is, he’s been able to use his incident to draw attention to the fact that YouTube’s failings on copyright are widespread and deserve repair. A petition he started has more than 100,000 signatures as of this writing.

Filtering content preemptively for copyright is a level of control that we should never give prominent content creators, as it threatens the public discourse, which is more important than any one piece of content created.

As I noted in a 2017 piece, the removal of copyright from content, as was common with mislabeled films produced in the 1950s and 1960s, has the inherent ability to create brand new ideas, to allow for a culture of remixes, and to enable business models. In the lean years of the home video industry before the big studios embraced its value, public domain films helped make VHS a success.

As someone who tries to dig through the seeds of history to recover lost ideas in new forms, copyright is often the biggest barrier to uncovering stories hidden by the passage of time—see my complaints about the necessary evil of Google Books’ snippet view. Content filters along the lines of the European Union’s Article 13 would further threaten that work, by preventing important content from even being seen—or discouraging people from uploading things that they found interesting just out of fear that it would be lost, anyway.

Large-scale content providers—including, it should be said, major publishers in the news industry such as Axel Springer, the German owner of American news site Business Insider—are doing what they can to protect their own bottom lines, without considering how damaging the side effects could be for our culture. Article 11, which would attempt to limit the use of aggregation tools such as Google News by making headlines copyrightable, would make my job harder—and yours, too. Spain already has a law like it, and it has decimated its news industry.

The fact is, the process of creation thrives when a degree of control is lost. Adding that control back, no matter how theoretically good it sounds for the bottom line of the film, music, or publishing industries, is just going to ruin things for the next generation of creators, who deserve the same levels of independence the current generation has had. Pardon my French, but we owe it to them not to fuck this up.

I’d like to finish this off by noting, in passing, that I had an incident happen this year where I deleted a series of tweets off of my personal Twitter account because a copyright holder complained. I don’t want to go into it, but that incident has probably shaped my views on copyright issues more than anything else that has happened this year.

Our current laws don’t do enough to allow for edge cases in digital culture, to consider the importance of protecting the small creator who doesn’t have a staff of 200 or a giant legal team backing them up. We need to be doing more to loosen the reins on what the average person can do with a piece of digital content, not the other way around. As has been proven time and time again, our culture wins when the big guys—like the RIAA—lose.

The European Union has shown a willingness to let them win—a willingness that is only weakening because the public is pushing back. And that should scare us.

On the other hand … As you may know as a Tedium reader, I have an extreme dislike for wall calendars, which I find to be outdated and often tacky. I’ve been surprised in the past by some of the wall calendars out there, but this year, I uncovered one for “Stoner Sloths,” and feel that it is my duty to share its existence with you guys, as it is so depressing and terrible that I feel I must share its failure as an object with everyone I know.

Next week represents a pivotal time for me as a creator of content on the internet.

New Year’s generally means two things in the Tedium household: It’s the time of year when I willingly scald my skin by attempting to make jalapeño poppers from scratch, and it’s also the anniversary of both Tedium and my old site, ShortFormBlog.

And next week is a big one. Ten years ago, on January 1, 2009, I spun up the wheels on ShortFormBlog, meaning I’ve been at the process of creating content intended for the internet for a full decade.

I realize that this being the last Tedium of 2018 feels a little early, a matter of scheduling. But next week, I’m going all out—with both some changes to the Tedium website and some broader content goals. I’m still working out the details, but the plan is that when you get the next issue of Tedium, there will be a new website online to host it. Hopefully, I won’t go nuts in the process—but I’m excited about it and what it means for the platform in the future.

But beyond what’s happening on the Tedium website, next week I want to get folks to think really hard about what it means to make content online—as well as the importance of owning it and operating it on your own platform. And to reflect this, next month I’m going to set out a plan of attack in two directions: One, I’m going to write content that highlights how awesome it is that we finally have new stuff entering the public domain once again; and two, I’m going to make a case for independent blogging.

With that latter point in mind, if anyone reading this has a New Year’s resolution to start a blog in 2019, email me a link and a quick one-paragraph description of what you plan to write about on your blog. I will promote it in the next issue of Tedium. (If I get, like, 50 links, I might have to push it over to a Daily Tedium post, but I promise I will draw attention to it.)

I want 2019 to be a year when blogging no longer feels like a thing of the past, because for some of us (author points thumb at himself), it’s never lost its luster.

Have a good New Year’s.

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium122718.gif)

/uploads/tedium122718.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)