Total Edutainment Forever

The problem with edutainment in the 1990s was that, while it covered the education, it didn't do enough to entertain the kids. Sorry, Math Blaster.

Hey all, here’s a classic Tedium piece about the traditional problem with mixing education and software. This story has a great alternative term for “edutainment,” BTW.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

“I thought I read somewhere that she had won a big typing contest, or that she ran a school, or something. There really is no Mavis? I can’t believe it.”

— Brent Bynum, a Philadelphia man who learned, after purchasing a copy of Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing, that Beacon is not a real person but a composite person whose face is a model’s and whose name is partly stolen from Mavis Staples. Vice had a pretty great feature about the game and its namesake back in 2015. Of note: The cover model had three-inch fingernails at the time of her 1986 cover shot, which seems like a bad choice if you’re a typist.

Math Blaster game box. (via GameFAQs)

The tutor who became a multi-millionaire edutainment innovator because she went to the wrong restaurant

In the late 1970s, it was pretty common for people in California and elsewhere to have an “aha” moment as they introduced a computer to their homes for the first time.

Famously, for example, the roots of Sierra On-Line—the groundbreaking games company behind such popular game series as King’s Quest and Leisure Suit Larry—came about in 1979, after Ken Williams bought an Apple II and his wife, Roberta, felt like the text adventure games she was playing on the machine would be better if they had graphics. The California couple soon had the graphical adventure game market cornered.

Professional tutor and fellow Californian Jan Davidson had a similar discovery. Davidson bought an Apple II to help get her after-school tutoring business off the ground, only to find that there weren’t any applications to assist with the cause. So, according to the New York Times, she contracted one out. The speed-reader program she created would turn out to be a building block for the modern education software industry, but not one as fundamental as a game she came up with as a follow-up.

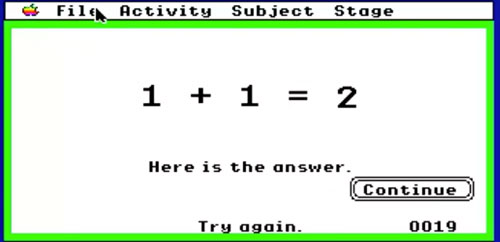

Math Blaster was inspired by the programs for math on the system at the time, which seemed to punish the student for an incorrect answer.

“They were dull and if a kid missed something they would make this horrible ‘beep,‘” Davidson recalled of her competition to the Los Angeles Times at the time. “Here you had this powerful tool for teaching and all you were giving a kid was negative feedback every time they hit the wrong key. And it was loud enough that everyone in the room knew that Johnny had made a boo-boo.”

This is a bad problem to get wrong.

So Davidson worked with a programmer to create a program that could be legitimately be considered both fun, and, well, math. It quickly became much more than a side hustle, especially after Davidson’s husband, Bob, convinced the reluctant software entrepreneur to jump into the software business with both feet—a decision she made reluctantly at the time, but a move that proved very lucrative.

(Fun fact: That decision came about because she was meeting with a software publishing company’s rep to talk about selling off her programs, but the rep was a no-show. Per the L.A. Times, the rep did show up—but at a different location of the same restaurant, on the other side of town. The lesson? Serendipity and luck go hand-in-hand.)

With Math Blaster as its centerpiece, Davidson and Associates became an educational publishing giant, publishing dozens of titles a year, with Jan Davidson emphasizing the importance of the games’ education content. Eventually, it became so big that it could focus on more than edutainment: In 1993, the company acquired a formative version of Blizzard Entertainment in the days before the release of WarCraft—a shrewd purchase of a company that would become one of the largest game developers in the world—but generally, it stuck to its education software guns.

Davidson’s namesake company was once so synonymous with education that its domain was Education.com. But by the late ’90s, the Davidsons had sold their company and parlayed its success into philanthropic efforts. (The Math Blaster series continues without them, gaining a Facebook-based edition in 2015.) The couple founded the Davidson Institute for Talent Development, a school based in Reno, Nevada, in 1999.

They chose their endeavor because it targeted gifted students, a segment of the student population they thought highly underserved. In their 2005 book Genius Denied: How to Stop Wasting Our Brightest Young Minds, they explain how they got on such a sharply different path:

People always ask us why, when we sold Davidson & Associates, our educational software company, and entered the world of philanthropy, we chose to work with gifted children. Our reply is that we have always wanted to help children become successful learners. Even before founding Davidson & Associates, Jan taught English at the college level and tutored children of all ages. Bob’s ideas for our math and reading software helped thousands of students discover that learning can be as much fun as playing video games. We want all children to have these “Aha’ moments. So we searched for the population that traditional schools serve least, the population that is least likely to learn and achieve to its potential. We believe that highly gifted students are that population.

As you can guess by that statement, the goal of entertaining was always secondary to education at Davidson and Associates. And while lots of kids have good memories of Math Blaster and other games of the edutainment era, it’s a game that receives a surprising amount of retrospective criticism from developers today.

In fact, there’s a surprising nickname for games of its ilk: “chocolate covered broccoli.”

“Whereas in the 1980s Nintendo released an average of one or two new Mario titles a year, the 1990s saw a flood of ill-conceived Mario spin-offs, such as Mario Teaches Typing, Mario’s Game Gallery, and Mario’s Time Machine. Although some of the worst titles were produced under license by third party developers, such as Philips and Interplay, the onslaught of mediocre Mario games nearly destroyed Nintendo’s most valuable franchise.”

— Authors Gloria Barczak and David Wesley, discussing the dilution of the Mario brand in the early ’90s in their book Innovation and Marketing in the Video Game Industry. While this dilution is largely associated by modern gamers with Nintendo’s ill-advised decision to let Philips make Mario and Zelda games for its CD-i console, the three examples cited the the authors are all edutainment games for the PC. (They let Interplay make bad edutainment games for the PC, but wouldn’t let id Software port Super Mario Bros. 3? Weird logic.) The marketing dilution situation wasn’t remedied until the 1996 release of Super Mario 64. The Internet Archive has Mario Teaches Typing, by the way. Practice your home row.

Just add chocolate.

“Chocolate-covered broccoli”: An evocative term that has come to define the edutainment era

If (like me) you do a search on Newspapers.com for the term “edutainment,” you’ll find that it had a surge in interest as a term in the early ’90s—a point after which some of the successes of the model had been proven by games like Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? and The Oregon Trail, two games in which education and entertainment found perhaps the perfect balance.

(In the case of The Oregon Trail, in fact, the game long predated any vestige of edutainment, which probably worked in its favor.)

Now, making the assumption that the surge of interest in the term “edutainment” did not come as a direct result of the Boogie Down Productions album of the same name, we can assume that the industry surged around this time. Clearly, there was a lot of success from a financial level, but to hear it now from education-minded game-makers now, it was not a creative success.

Math Blaster, for all its success, is seen as a key example of this kind of game—a drill sheet without the paper.

“You could probably get kids to play this for a while and think they were having fun, but after a while they’ll figure out that you’ve handed them what we in educational games like to call chocolate-covered broccoli,” noted Anastasia Salter, PhD, a digital media academic at the University of South Florida, in comments at the 2014 American Psychological Association’s Education Leadership Conference.

Just add broccoli.

Yes, “chocolate-covered broccoli.” The term, coined in 2001 by author Brenda Laurel in her book Utopian Entrepreneur, speaks to the idea that many forms of edutainment poorly integrate the entertainment part of the equation—leading to a result that still tastes pretty bad, even though it has something really sweet right on top.

It’s become sort of a rallying cry for education-minded game developers these days, which have largely eschewed the term in favor of one that probably makes more sense for the game industry’s goals: “Serious games,” a phrase popularized by a 2006 book of the same name by authors David Michael and Sande Chen.

In an article reflecting on the issue from 2016, Chen noted that there’s a belief among developers that the game has to be as good as the education—if not better.

“Many developers have found prioritizing entertainment over education can yield the desired results,” Chen writes. “Kids would rather play an entertainment title over an educational one, even if that entertainment game makes them learn astrophysics.”

It’s sort of like how my wife attempts to get me to eat beets by mixing them with a bunch of other stuff in the juicer. It doesn’t always work, but at least she’s trying.

The subject of edutainment is a common one for mockery. Blizzard Entertainment—which, remember, was purchased by an edutainment giant in 1993 and likely owes much of its early success to the additional distribution gained from that move—once created an April Fool’s parody called Blizzard Kidzz that mocked games like The Oregon Trail and Mario Teaches Typing. (A bit unfair, but funny!)

But just because the games of the era were kind of terrible doesn’t mean that’s the upper limit for edutainment. It makes sense that educators have recently found more luck with introducing Minecraft to the classroom than Math Blaster. Often, the best education isn’t deliberate.

That lesson was hard to find two decades ago, when Mattel found it had purchased a lemon from Shark Tank loud guy Kevin O’Leary with The Learning Company. Mattel spent $3.6 billion on the business, only to sell it off a couple years later for basically nothing. Not even the fact that The Print Shop was part of the purchase could save the deal.

It worked out for O’Leary, who CNBC thinks is the most interesting person on earth these days, but the edutainment space never really recovered.

In comments to EdSurge, Lee Banville of Games and Learning noted that The Learning Company’s failure shows the complexity of the problem.

“The Learning Company showed that mixing games with education is a powerful tool, but it also showed how difficult it is to grow that business and diversify and evolve,” Banville said.

The Learning Company deserves more credit than it’s getting in the modern day, and so, too, does Jan Davidson, who uncovered a genuinely important trend with Math Blaster.

But, to be clear, you can’t just put Mario on a boring game and hope that kids learn something in the process. Considering how sophisticated games are getting these days, that’s not good enough.

And you can’t do that hundreds of times over with little variation and hope that it sticks—which is what the edutainment market felt like in the ’90s.

Kids are way smarter than that.

--

Find this one a fascinating read? Share it with a pal! And see you next week. Cheers!

:format(jpeg)/2017/04/tedium0413_email.gif)

/2017/04/tedium0413_email.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)