The Wires Barely Reach

It took a while for the internet to turn into a major global force, but it wasn't for lack of trying. (Peter Gabriel deserves at least some of the credit.)

Hey all, last week’s piece about planned obsolescence—and some of the response it drew—got me thinking about connections to the internet, or lack thereof. With that in mind, I pulled this old piece out of the archive and updated it some. It’s a reminder that globalization of the internet wasn’t always a given.

Love Tedium? You should sign up for Numlock News, a snappy morning newsletter full of great stories. Thousands wake up to it every day because it’s smart, funny, statty and free. Sign up right now and start getting the highlight of your morning.

A damaged building in Belgrade, Serbia. (David Holt/Flickr)

The BBS that kept Serbia informed while NATO was lobbing bombs all over the place

When the bombs started falling in Belgrade in March of 1999, NATO was trying to force Yugoslav forces out of Kosovo. For 78 days, the country was bombed and its infrastructure damaged, all while media outlets were muffled from reporting on the war by the Yugoslavian government.

One piece of infrastructure that didn’t fall apart during the spate of bombings was SezamPro, a bulletin board system that helped create an ad-hoc way for people on the ground to get an understanding of what was happening in their country.

SezamPro was an outgrowth of one of the country’s most popular BBS systems, Sezam. While not the first BBS in Yugoslavia, the chatline-style conversation approach proved popular with users, and quickly, the service gained numerous fans. People were willing to pay $80 per year for the service despite the slim wages in the country.

While Serbs got an early opportunity to use email during the ’80s, that setup was eventually cut off in the midst of the Yugoslav wars starting in the 1990s, a period in which Serbia was seen as the “bad guy” internationally.

“We lived in a country under a blockade and had to do all the work ourselves,” noted Dejan Ristanovic, Sezam’s co-founder, in a 2016 speech at a Hackaday conference in Belgrade.

Sezam, which was founded in 1989, played this role for years, but eventually the service required a major upgrade to support faster modems and eventually, internet access. The Sezam service evolved into SezamPro, which for more than a decade, was the primary way that Serbians got online.

(“We lost all of the wars, so we were still the bad guys. But we were defeated bad guys, and defeated bad guys could have internet access … but it has to be slow,” Ristanovic, who is a prominent technology journalist in Serbia, said of the access they received.)

In the end, SezamPro’s breakout moment came not because it had the internet, but when NATO started bombing Serbia, in an effort to convince the military to leave Kosovo. SezamPro’s much stronger capabilities for holding people—it could handle up to 100 users in its chat room at once—made it a valuable tool for Serbians who were simply trying to figure out what was happening.

According to a report from the online peer-reviewed journal First Monday, SezamPro effectively became a media outlet itself. An excerpt:

This role of the SezamPro chat lasted during the entire War. Night after night, the chat brought together a number of members of the system, up to one hundred of them, which was the highest number of participants the service could technically support. They chatted during the night, since that was the time when NATO attacks were predominantly performed. Chat sessions usually started just after the air raid alarms and together with the first explosions the number of participants increased. As soon as an explosion was heard, new chatters would join, asking: “What did they hit?” The Sezam’s “alternative net of reporters” would then try to identify what had been hit. The participants from different parts of the city were giving eyewitness reports. An internal scale on the intensity of explosion was established, so the mark 10 meant that the window glass broke, 9 that the window glass shook, 8 that the explosion was very strong but with no obvious consequences and down to mark 1, which meant the situation was peaceful.

Political conversations weren’t uncommon on SezamPro and its predecessor (as can be seen from this lengthy list of comments taken immediately before Yugoslavia fell apart), but the bombings took things to a whole new level.

These days, the network is still active, but not in the form you would expect: If you load up http://sezampro.rs/ in your browser, you’ll get a page for Orion Telekom, the firm whose parent company bought SezamPro in 2009. But if you telnet in to telnet.sezampro.rs, you get a login screen. The old network still exists. It’s not the same, but it’s there.

Yeah, it’s primitive. But it was primitive in 1999. Those messages, hiding behind the login screen, deserve to be preserved: They helped keep a semblance of normalcy for those in Serbia affected by the decisions of leadership but with no say in how those decisions were made.

“Nudity and pornography were quite ‘verboten’ in those calvinistic days; even some of the so-called ‘subversive literature’ readily available on many BBSes might have resulted in you accidentally falling down a flight of stairs while in police custody a scant five years before.”

— Herby Hönigsperger, onetime operator of a BBS system in South Africa called HMVH Corporation, discussing the political climate of the country in the early ’90s—and how his BBS and others subverted that climate. (FYI, some NSFW images in the link, mostly meant to highlight the point he makes in the quote.) Hönigsperger’s BBS launched in December of 1994, at a time when the country’s BBS scene was fairly vibrant, with hundreds of different systems. (That said, the phenomenon was almost entirely white and male: “Not a single BBS operated out of a ’black township,’” he wrote.) Hönigsperger runs a website dedicated to the legacy of the BBS scene in South Africa.

How Peter Gabriel helped the internet gain its global reputation

Here’s a fun fact about the internet that you probably aren’t aware of, until you really think about it: Its global, online nature wasn’t a given for decades after its launch. In fact, it took a lot of time for the internet to reach many of the world’s developing nations.

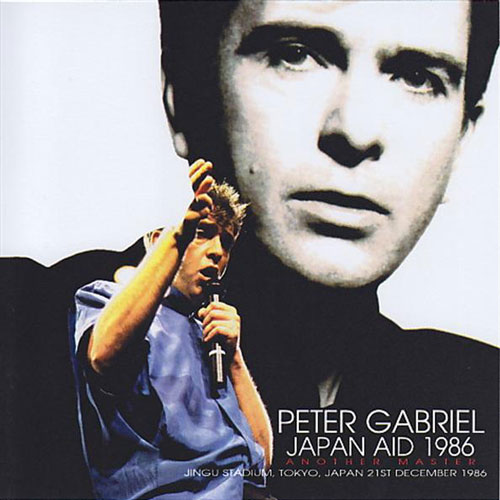

And we arguably have Peter Gabriel to thank for fixing that situation. At the height of his success in 1986, the man whose voice launched a million boomboxes thought it would be a great idea to launch a charity event with the goal of funding a global peace network.

Not that anyone remembers Japan Aid, the festival Gabriel put on in the waning days of 1986. Part of the obscurity was by design: Gabriel and his fellow organizers chose not to accept sponsorship deals that would have put the show on television, out of the interest of integrity.

“Of all the charity events and causes in the eighties, this is perhaps the most obscure,” noted Collectors Music Reviews. “A video featuring some performances from the event was released in 1987 but quickly went out of print and the entire festival has lapsed into obscurity.”

So yes, the festival—featuring Lou Reed, Jackson Browne, and Howard Jones among numerous other acts—was no Live Aid. But it was a money-maker, and its fundraising helped launch an organization that has had a much broader impact than the actual show did.

(Also, let’s be fair: A Peter Gabriel concert in 1986 was probably a freaking treat.)

The Association for Progressive Communications (APC), a group that was literally named in Gabriel’s hotel room, brought together a few peace-oriented networks that were running active BBSes at a time when the technology was relatively rare, and helped offer email to far-flung parts of the world through Fidonet, a relay system that helped BBS systems support email using a series of nodes. (Fidonet worked like a series of waystations, passing messages from one BBS to the next.)

The approach was built from a number of disparate parts—a handful of advocacy-focused nongovernmental organizations getting their start around this time were launching with missions intended to help bring the world a little bit closer together. A total of seven networks joined the group at the time of its 1990 launch: The U.K.‘s GreenNet, the United States’ PeaceNet (also known as the Institute of Global Communications), Nicaragua’s Nicaro, Sweden’s NordNet, Canada’s Web, Brazil’s iBase, and Australia’s Pegasus.

In a 1987 paper, APC cofounders Mitra Ardron of GreenNet and IGC’s Deborah L. Miller saw a lot of potential for the networks as a tool for citizen action—something enabled by digital communication offerings like those offered by their networks.

“Our commitment is to truly global communication—communication available to the social inventors, the grassroots activists, and the organizational leaders creating a future that works for everyone. That’s the difference that makes a difference,” they wrote.

(Not that it was cheap: According to the document, both networks at the time had an hourly fee for use that topped $10.)

Ultimately, the network grew and blossomed into something amazing to behold, and provided many developing nations their first online connections—among them Cuba, which received its first online connection via APC in 1990.

(Additionally, the network’s influence had impacts on other parts of internet culture—for example, the current director of the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, Mark Graham, is an APC cofounder. Graham is featured in this video about the concert.)

In 2015, APC’s unsung work in combining the internet with activism worldwide helped the group win an Electronic Frontier Foundation Pioneer Award.

Gabriel was one of the first to applaud them—and he took as little credit as possible.

“All the countries of the continent were supplying information to databases and we wanted people to access all the information stored in them. At that time there was not a single public library in Ethiopia.”

— Nancy Hafkin, a onetime leader of the Pan African Development Information System, discussing with Wired her role in helping launch the internet on the African continent. Hafkin, seeing how poor the alternatives were (people were accessing databases by sending letters through the mail!), was inspired with her team to help launch some early digital networks as a firm alternative.

It’s strange to think about the fact that the internet didn’t instantaneously turn on one day for the entire world, that there were significant growing pains at a time when Growing Pains was still on the air in the U.S and we had no idea Kirk Cameron was religious.

Logically, it makes sense. Disruptive technologies like air conditioning, telephones, and light bulbs took decades to reach the bulk of people in the U.S. alone.

But we’ve been sold on this idea, this vision that the internet is global and always has been. And when we hear about Serbia’s early challenges in getting an internet connection or the idea that a bunch of NGOs did the tough work needed to get Ghana online, we’re not sure what to think.

It feels like there’s a disconnect somewhere, in the way we think about this digital world.

--

If disconnects are something you think about on a regular basis, be sure to give my latest Twitter endeavor, The Right to Preserve, a look.

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal! And thanks again to Numlock News for the support.

:format(jpeg)/2017/06/tedium090116.gif)

/2017/06/tedium090116.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)