The Internet's First Election

The web wasn't common in 1992, but presidential candidates notably took baby steps toward the internet that year—Ross Perot in a bigger way than most.

Hey all, Ernie here with a refresh of a timely article about the internet and presidential elections. The internet has been a deep influence on the 2020 election in stark ways. Given that, looking back at how things started strikes me as important.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

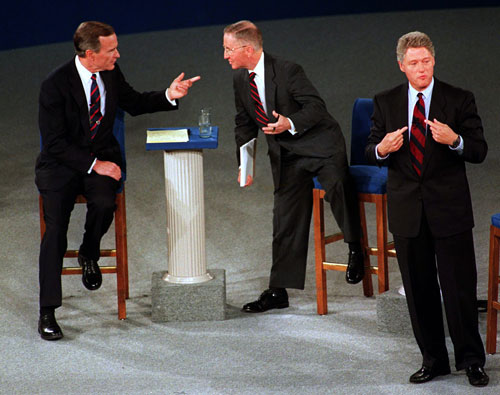

(via the National Communication Association)

Five interesting ways technology influenced the 1992 presidential election

- Prodigy, the Sears-affiliated early online service that directly competed with AOL for a time, launched a 1992 campaign database for users to track candidates. The effort came about thanks to a collaboration with the League of Women Voters. Even better, Prodigy allowed you to write your representative electronically—well, kinda. “If you want to get your view across and write to your representative, you can write a letter on the computer screen,” The Washington Post noted in February of 1992. “Prodigy will print and mail it for a fee of $2.50.”

- For his 1992 primary campaign, current California Gov. Jerry Brown innovated by using a 1-800 number to solicit donations. Sound kind of quaint? Don’t be fooled: This was a Big Deal in 1992, as it hadn’t properly been utilized by candidates previously. As the San Francisco Chronicle learned back in 2013, the widely disseminated number, (800) 426-1112, was still active and owned by Brown. But as of 2020, it no longer appears to be.

- Jerry Brown also used Compuserve to reach voters, but so, too, did the Lincoln Chafee of the 1992 campaign, former Irvine, California, mayor Larry Agran. Agran, who didn’t last beyond New Hampshire, held online Q&A sessions on the early online network, with Bloomberg noting that Agran would speak out answers to the online questions out loud, while a transcriptionist would type the answers into the computer.

- Usenet! Freaking Usenet! The 1992 campaign was a hot topic on Usenet, the decentralized newsgroup system which is best described to those who never experienced it in person as the Reddit of its day. There were groups for all of the major candidates, as well as ample evidence that people didn’t like Bill Clinton even back then, and Ross Perot was a hot topic way back when. (Side note: Many newsgroups from the era are still active, including one for Rush Limbaugh.)

- MIT-programmed mailing lists: In 1992, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology ran a number of email-driven bots on the campaign92.org domain, allowing users to request position papers for any campaign on the ballot in at least half of U.S. states—which meant Libertarian Party candidate Andre Marrou and Natural Law Party candidate John Hagelin got mailing lists, too. (Not that Hagelin got any respect—the MIT press release at the time called him “Larry.“) MIT estimated that the in the days before the 1992 election, it was sending out 2,000 emails a day through the accounts.

“One little-noticed development that illustrates the interactive nature of modern technology is the use of electronic mail. During the general election campaign, the text of all Bill Clinton’s speeches as well as his daily schedule, press releases, and position papers were made available through on-line computer services, such as Compuserve and Prodigy.”

— Dee Dee Myers, Bill Clinton’s first White House press secretary, discussing in The American Behavioral Scientist, an academic journal, how the Clinton campaign pioneered the use of online communications during the 1992 campaign. Myers characterized the endeavor as democratizing what would have previously been private pool reports. “For the first time, ordinary citizens had an easy way to obtain information that was previously available only to the national press corps,” she noted. “Instead of seeing an 8-second sound bite chosen by a network producer, voters could read an entire speech.” Clinton later became the first president to launch an official email address—[email protected], of course—and website. (In case you’re wondering, George H.W. Bush’s use of the internet during the 1992 campaign was much more, uh, conservative—limited, according to the Routledge Handbook of Internet Politics, to emailing policy statements and speech transcripts to bulletin boards.)

Ross Perot (Wikimedia Commons)

How Ross Perot’s 1992 campaign helped pave the way for the Internet Archive

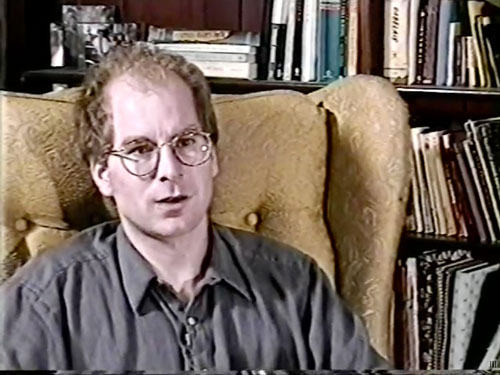

Back in 2015, the Internet Archive’s Jason Scott uncovered a piece of archival material so obscure that even the organization’s founder, Brewster Kahle, didn’t remember creating it. The two-hour-long video, previously unmarked and with fewer than ten views at the time Scott discovered it, features an interview with Kahle that dates back to his days as head of WAIS, Inc., an early attempt to create a broad online database.

WAIS, which stands for “wide area information server,” was effectively an internet-enabled database technology that allowed for long-distance access of digitally organized content. Initially borne in 1989 from a research project, it became something of a footnote in the history of the internet as a combination of the World Wide Web and search engines like Google took its place. But the thinking in its design was, in some ways, fundamental to the way we use the internet now.

The technology, at the time, was seen as particularly valuable—especially in the days when it wasn’t clear how we would eventually access data online. Spun off from the supercomputer firm Thinking Machines in 1992, WAIS, Inc. represented one of the first attempts to make the internet user-friendly.

And, as a company, it got its start thanks to a presidential campaign—Ross Perot’s, to be specific. As Kahle states nearly an hour into the video, the campaign basically was the reason why the company was created when it was. In fact, Kahle described it as a “fortuitous event”: He knew Perot Systems head Mort Meyerson, who had a sudden need for an information-organization platform for the campaign of the company’s namesake.

Brewster Kahle, circa 1992. (via the Internet Archive)

“Basically they’ve got this organization of people that are in 50 states, that is ad-hoc, that has three months to live, that has to keep in touch with each other,” Kahle explained in the clip. “So they have lots of information coming from the field, and they have, they need to collect up in a central place, figure out what it is they’re trying to do, what the statements, positions of Ross Perot are, and to disseminate that information out again. Paper, or having people fly back and forth, just wasn’t fast enough. Electronics made a whole lot of sense within a campaign structure.”

The high-tech approach considered by the Perot campaign makes a lot of sense. As is well-known, Perot (who died last year at the age of 89) had a significant background in technology, as the founder of Electronic Data Systems, a information technology management firm that dates to the 1960s. (He also famously invested in Steve Jobs’ NeXT.)

Kahle’s system, put together in a couple of days, impressed political strategist and campaign manager Ed Rollins, who quickly put the system to work for the campaign. Soon after, Rollins quit the campaign, and Perot famously suspended his effort before eventually hopping back in. This created a problem for Perot Systems, which had this impressive tool at its disposal that it no longer could use for its intended purpose—organizing news clippings and press contacts.

(If you know where to look on the Internet Archive, you can actually find the proposed statement of work describing this effort to create “an Intelligence System for the Perot Campaign.“)

Eventually, with WAIS Inc.‘s help, Perot Systems decided to eat its own dog food.

“Basically Perot Systems’ point was, ‘What could Perot Systems use this for?’ in terms of selling it to their customers,” Kahle explained. “So we installed it within Perot Systems to help them run their own corporation. And that, now it’s November of ’92, we’ve basically installed it and got it running for six months. The pilot groups are using the system for all sorts of information.”

Soon enough, WAIS, Inc., off the back of client work like the Perot campaign and other projects, became a successful, profitable business, one that was only slightly ahead of its time—and close enough in conceit to the web that it basically predicted the internet’s future.

As the internet started to take a more formalized shape, Kahle and other stakeholders sold WAIS, Inc. to AOL, and with the money earned from the buyout, he and fellow WAIS co-founder Bruce Gilliat started two projects that are still active to this day: Alexa, an online search and analytics tool that crawls the internet’s many websites, and the Internet Archive, which keeps the internet’s memory safe for generations to come. (They eventually sold Alexa to Amazon for $250 million in stock. It’s unrelated, except perhaps in spirit, to Amazon’s Echo-driving AI project of the same name.)

As the 1996 election was just ending—with the internet’s role in future elections secured, thanks to sites like Clinton/Gore ’96 and Dole/Kemp ’96, Kahle was getting a start on the project that would become the internet’s ultimate scrapbook.

On October 26, 1996, the Internet Archive began in earnest, helping to collect big statements and tiny wrinkles alike on the internet. (Did you know they accept donations?)

That broad swoop of data collection extends to the world of politics. The Archive has in some ways democratized the basic ideas that Kahle’s campaign machinery was built upon back in ’92. During the 2016 campaign, the nonprofit’s Political TV Ad Archive collected every political ad that has run during that campaign season (including links to fact-checks of the ads), along with granular data about each of the presidential debates—the latter with the help of the Annenberg Public Policy Center. What WAIS was doing for Perot’s campaign way back when, the Political TV Ad Archive expanded upon.

This time of year in the ’92 election, Ross Perot was making some unusual left-field moves in an effort to topple Clinton and Bush–memorably, he ran a series of prime-time infomercials ahead of the election, which he paid for out of his own pocket because he’s Ross Perot. Perot didn’t win in ’92, in part because his decision to drop out of the race, then return, didn’t sit well with some.

But just imagine how effective those ads could’ve been if they had the full power of Brewster Kahle’s database behind them during that three-month break Perot took.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

:format(jpeg)/2017/06/tedium101816.gif)

/2017/06/tedium101816.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)