All You Need Is Weird

The Beatles might have been the most mainstream band in history, but many of their inspirations were hugely obscure—and inspired obscurities of their own.

Hey all, Ernie here with a refreshed piece about The Beatles, in honor of John Lennon, who we lost 40 years ago this week. We’re choosing to focus on the fun times.

Sponsored By … You?

If you find weird or unusual topics like this super-fascinating, the best way to tell us is to give us a nod on Ko-Fi. It helps ensure that we can keep this machine moving, support outside writers, and bring on the tools to support our writing. (Also it’s heartening when someone chips in.)

We accept advertising, too! Check out this page to learn more.

One way The Beatles managed to stand out at the beginning of its career? Inspiration from John Lennon’s love of random B-sides

If you dive into The Beatles’ many songs, one that has never really gotten its due is “Mr. Moonlight,” a song that even many Beatles fans think isn’t very good. It has elements that, as a piece, feel all wrong together. The song feels vaguely Latin in inspiration, and while John Lennon’s vocal performance cuts through, the song unusually seems to drag … not a good thing for a song that lasts 2 minutes, 38 seconds.

And then there are the weird musical elements. At one point, George Harrison starts playing a damn organ—which is the part people hate the most about the song.

But the secret with the song is that it reflects the band’s willingness to find inspiration in strange sources. Particularly, at this time in their career, on B-sides or obscure deep-album tracks. While most bands of their era would cover A-side singles, The Beatles dug around for the unusual songs on the flip side, and when they found inspiration, they would introduce this material into its live show … and because everyone else was covering the same old stuff, it stood out.

In comments in The Beatles Anthology, Paul McCartney explained that this tendency to go off the beaten path quickly inspired other bands:

There were millions of groups around at the time—The Blue Angels, The Running Scareds—but they were mostly lookalike groups. The Shadows and Roy Orbison had a lot of followers. Then there were groups like us, more into the blues and slightly obscure material. And because we had the unusual songs, we became the act you had to see, to copy.

We started to get a lot of respect. Guys would ask where we’d got a song like “If You Gotta Make a Fool of Somebody” from—we’d explain it was on a James Ray album. The Hollies came to see us once and came back two weeks later looking like us!

This was how they (Lennon specifically) found “Mr. Moonlight,” which became a staple of their live shows years before it appeared on the UK-only album Beatles for Sale, which leaned heavily on covers from their pre-fame days.

Originally a song performed by Dr. Feelgood and The Interns and written by Interns member Roy Lee Johnson, the song was a bad fit for The Beatles, but the inspiration that led them to play it in the first place was completely on-point.

The strange covers eventually gave them artistic license to introduce their own songs, and the rest, shall we say, is history.

Lennon’s love of weird musical inspiration from this era stuck with him years later, something which was on display during an interview with Rolling Stone contributing editor Jonathan Cott in which he played off a bunch of old 45s from the early ’60s.

As Boing Boing pointed out earlier this year and Cott recalled in his book Days that I’ll Remember: Spending Time with John Lennon and Yoko Ono, one of the songs Lennon played for Cott was “Give Me Love,” the B-side of one of his favorite songs, Rosie and the Originals’ “Angel Baby.”

Lennon loved “Give Me Love” because it was awful and clearly recorded in a slapdash manner. As he explains without the benefit of the cultural reference, it’s the B-side version of The Room:

“This is really one of the greatest strange records,” [Lennon] remarked. “It’s all just out of beat, and everyone misses it. The A-side was the hit, ‘Angel Baby’—which is one of my favorite songs—and they knocked off the B side in ten minutes. I’m always talking Yoko’s ear off, telling her about these songs, saying, ‘Look, this is this! This is this… and this… and this!’”

We have lots of evidence of this, but a big reason why The Beatles found wide-scale success comes down to the fact that they were huge music nerds—always looking for inspiration in the places nobody else would.

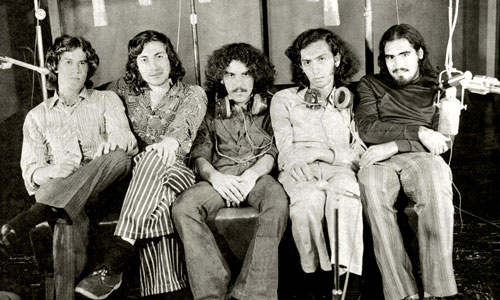

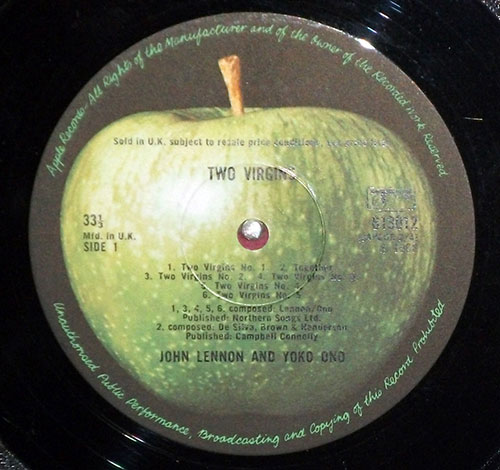

The Peruvian rock band We All Together quietly and obscurely carried the Beatles’ torch

Sorry Oasis, but We All Together beat you to that whole aping-the-Beatles thing by more than two decades. And unlike Badfinger, they didn’t have help from the Beatles themselves in making their tuneful pop.

We All Together is pretty much completely unknown outside of their native Peru, outside of their song “It’s a Sin to Go Away.” That tune, a spectacular bit of fuzz-bass and drum-pounding dramatics, showed up on the second volume of the Nuggets box set, deservedly giving the band some garage-rock cred.

But that song and its modest international profile, in a way, does We All Together a disservice. It’s a powerful tune that (apologies to fans of Os Mutantes and Gilberto Gil) is potentially the best rock song to come out of South America in the 1970s, but it sort of clouds the fact that, much like The Beatles, We All Together’s original run is best seen as a full piece.

The band, which released two albums in the 1970s, was known for creating original songs that were so in the spirit of late-period Beatlemania that they may as well have found a place on Abbey Road or Let it Be, or (more likely) a Beatles solo album. Part of the reason for that was that the recording quality of these songs was extremely high, to the point where, if you didn’t hear lead singer Carlos Guerrero’s slight accent, you would have no idea you were listening to a band that hailed from Lima.

The band had a lot of time to polish its chops. Guerrero and the other members of the band (Carlos Salom, Manuel Cornejo, and Saúl Cornejo) built their chops as members of another Peruvian band, Laghonia. By the time the members shifted to We All Together, they were good enough at their craft that they could mimic some of the Beatles’ best studio tricks.

Both of the original band’s albums, a self-titled release that came out in either 1972 or 1973, and the 1974 follow-up Volumen II, are driven by Paul McCartney’s ear for tunefulness and Guerrero’s vocals, which evoke the nasally parts of John Lennon’s iconic register. They never straight-up covered the Beatles during this era, but they covered a lot of songs in the Beatles sphere, including tunes by Wings and Badfinger’s “Carry On Until Tomorrow.”

As a cover band, they were impressive. Just compare their rendition of “Band on the Run” to McCartney’s version.

But when they were creating their own songs—like “Ozzy,” a highlight of their second record—it didn’t sound like they were imitators to the Britpop throne.

Like all good music with interesting backstories, these albums have only resurfaced outside of Peru within the past two decades, thanks to specialty labels such as Light in the Attic bringing them back to life. But the band itself remained active for nearly 40 years (and Guerrero the only constant), only hanging it up back in 2011, with a few more recent releases showing up on iTunes. It took them all the way until 1996 to record a straight-up album of Beatles covers, much to their credit.

three

The peak UK chart position of Paul McCartney’s solo single “We All Stand Together,“ a literal nursery rhyme that McCartney wrote for the animated TV show Rupert. (No clue if the song’s name was a knowing nod to We All Together going out of their way to clearly ape him.) Macca was a huge fan of Rupert the Bear as a kid, to the point where he not only wrote this song for it, but he also co-wrote Rupert and the Frog Song, the short that included the song, and aired the short before his terrible 1984 movie, Give My Regards to Broad Street. He went so far as to record an entire album of Rupert songs (arranged by George Martin, of course), but that album never saw the light of day. How did Macca’s Rupert theme song become such a big hit? He released it as a single just before Christmas, of course, because he knows how to make money.

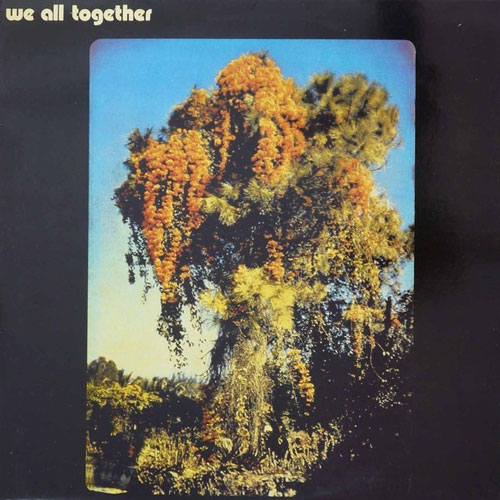

Four awesomely random albums the Beatles released on Apple Records

- John Lennon and Yoko Ono drew a lot of attention by showing up naked on their infamous 1968 album Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins, but the shocking part of that album may have been the record itself, which very much toyed with the avant-garde. The approach of its follow-up, Unfinished Music No. 2: Life with the Lions, was surprisingly blog-like for the 1960s, using music to highlight the couple’s quite-crazy day to day, which included protests and a miscarriage. One track on the latter record, “No Bed for Beatle John,” was literally the couple singing press clippings about themselves.

- George Harrison’s experiments with a Moog, on an album he called Electronic Sound, represent perhaps the biggest stretch Harrison took in his career—and it was a stretch that no other Beatle had tried by that point, though Paul McCartney later got the bug thanks to his side project The Fireman.

- Composer John Tavener, who eventually became known for his religious works, was sort of working on a religious wavelength when he recorded and released The Whale, a work inspired by the Old Testament story of Jonah, on Apple in 1968. But he was knee-deep in the avant-garde at the time, making his cantata a jarring composition for those unfamiliar with the avant.

- The Beatles’ Christmas fan club records, which were clearly designed to allow the band to mess around in the studio, are bizarre as heck, and pretty wild listens. The short records were initially only released in the U.K., but Apple released them as a full album to the U.S. market. Tiny Tim shows up at some point.

“For f&@! sake do something with ‘Sweet Music’ By Lon and Derrek Van Eaton. It’s a potential No. 1 hit.”

— George Harrison, writing in a telegram to the brass at Apple Records, expressing frustration that the label was failing to promote a song he produced. Lon and Derreck Van Eaton were two of the last artists to be signed to Apple Records, and soon after their album’s release (and its eventual failure), Apple stopped releasing music by artists other than the Beatles. The label had a reputation for not treating non-Beatle artists well; most famously, Badfinger titled one of its albums Ass, with the record featuring cover art designed to critique the band’s relationship with the record label. Lon and Derreck Van Eaton, meanwhile, saw their album Brother go out of print for nearly four decades.

It’s often forgotten today, but Beatles producer George Martin had a career outside of the band. He produced hit records before he met the Fab Four, and he even produced the most popular single of all time, Elton John’s “Candle in the Wind 1997.”

But perhaps the most interesting non-Beatles record he was associated with came about during his time with the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in the early ’60s.

Martin and a co-worker of his, Maddalena Fagandini, played around with an interval signal created by Fagandini, and ended up coming up with “Time Beat,” the first commercial music single ever released by the BBC. It didn’t become a hit, but it was an impressive feat. The single doesn’t sound like it’s more than 50 years old, which is saying a lot.

Martin’s musique concrète experience came in handy a few weeks after the single’s release, when Martin met the Beatles for the first time—this band that already had a taste for oddball music, that was digging around record stores for weird songs to cover.

It might have turned out to be a perfect match.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

:format(jpeg)/2018/01/jcetmhtd1yiyllui26zd--1-.gif)

/2018/01/jcetmhtd1yiyllui26zd--1-.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)