Belt, Buckled

The legacy of the seat belt, the world’s most prevalent safety device, and the act of corporate goodwill that ensured everyone‘s car got the best design.

Sponsored By Nightfall

Are API keys or other sensitive data in your logs?

Learn how to find out what you are logging with Nightfall's Developer Platform and our new Fluent Bit filter plugin here.

“European and American practice are in agreement on the point of not providing parachutes. As for safety belts, British and Dutch opinion is against their installation. Most of the transports operating in the United States do not provide belts for the passengers, but it is being demonstrated rapidly that they are sometimes necessary.”

— Charles N. Monteith, the chief engineer of Boeing, speaking to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers in a 1929 presentation, covered by The New York Times, that discussed at length the need for various amenities on aircraft. Yes, that’s correct; at one point parachutes were discussed as a potential option for passengers. Humor aside about this, seat belts were first commonly seen in airplanes before they appeared in cars.

The highly tested, highly used seat belt. (Jasz Paulino/Flickr)

Let’s talk about the fabric that seat belts are made out of, because it’s pretty awesome

Clearly, you’ve likely held a seat belt in your hands sometime during your stay on Earth, but have you ever examined the belt? It is an amazing piece of fabric—one that’s tough as nails and designed to last for decades. Odds are, if you find yourself in a junkyard checking out a dilapidated vehicle, the best looking part of the entire car will be the seat belt, thanks in no small part to its fabric design.

The fabric, also known as “webbing” in reference to the weaving process used to hold it together, is incredibly strong, in part because it has to be. Often made of synthetic materials like nylon and polyester (just like other fabrics in modern vehicles), the tensile strength of a seat belt has to meet certain standards, because you never know when that strength has to be put into use.

One of the benefits of a highly regulated material that has been used in literally billions of places over a 60-year period is that most of the kinks have been worked out, and lots of research has been done into edge cases. If a new edge case comes up, eventually it will get added into new regulatory standards.

To further underline the point: Click in this document about federal motor vehicle safety standards and do a search for the term “webbing”—you’ll find it comes up 281 times, despite it being a very obscure technical term that really only means something to folks who worry about things like textiles, such as Tedium editors.

Because you can buy literally anything on Amazon, I just wanted to let you know that extends to the fabric used to make seat belts.

On top of that, it gives the material certain unique elements compared to the way that we think of most woven materials: Unlike, say, a T-shirt, it’s not really all that water absorbent, and because it’s so tightly wound already, it tends to avoid issues like shrinkage. (And unlike corduroy, you won’t find any wales in a seat belt.) It’s hard to tear a seat belt as well, and often requires a cutting tool of some kind to tear it apart.

And seat belts have a tendency to be deeply considered from a design perspective, both from the position of strength and comfort—if you’re driving in a car for 10 hours, you don’t want to be wearing a seat belt that drives you nuts. Which means that while it’s strong, “military-grade fabric” lost out to “basic creature comforts.”

And like I mentioned above about those Chrome Industries bags (which use three-panel webbing on their straps, just like many seat belts), the design of seat belts has directly inspired the designs of other products. Of course, the modern seat belt—while invented more than 100 years ago—had inspiration from the defense industry, which spent much time testing different kinds of harnesses and other structures during World War II.

The fabric used in the modern seat belt, whether you think of it this way or not, may be the most thoughtfully considered roll of fabric you’ve ever used.

It pretty much has to be. Your life could depend on it.

A lift-lever-style belt buckle, of the type used on airplanes. (Sun Brockie/Flickr)

Five interesting facts about seat belts, a fundamental modern-day safety mechanism

- The concept of the seat belt long predates the automobile. The idea gained attention from an early British aerospace pioneer, Sir George Cayley, who came up with a number of important ideas for transportation technology. In an 1840 essay discussing safety mechanisms for trains, he wrote of a “broad padded belt to be placed in front of each passenger, to retain him in his place in case of accident, and to prevent a collision with each other.” (Ironically, most seats in Amtrak trains don’t actually use seat belts.)

- There’s actually a reason why your seat belt always gets stuck. Ever run into a situation where the seat belt won’t offer any more slack because you pulled it the wrong way? This is actually a function of its design. Basically, the belt uses a retractor that is designed to lock up in a case of sudden motion, so as to secure the passenger in the vehicle in their seat. In other words, if you jerk it in a way akin to how a seat belt might move when you press hard on your brakes, it’s going to lock up, requiring you to let the whole belt retract. (Here’s a useful YouTube clip on how the mechanism works.) It may be a bit annoying, but it might just save your life.

- Nearly everyone—but not quite everyone—uses seat belts. The use rate of seat belts in the United States was 90.4 percent in 2021, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, a solid level, albeit one that still leaves open a significant gap—that means 9.6 percent of people don’t wear seat belts, or 27.4 million people.

- Airline seat belts aren’t made equal. If you’re a “customer of size,” you might find the rigamarole around seat belts in airliners to be a bit annoying, especially due to the fact that you might need a seat belt extender just to get in the seat safely. So who gives passengers the most slack? The website TripSavvy reached out to every major airline and found that the best airline, by seat belt length, is Aeroméxico, which offers a 51-inch belt along with a 22-inch extender. Right behind is Hawaiian Airlines, with the same-size belt and a 20-inch extender. Most major airlines, like Delta and Southwest, fall below 40 inches for their belts, while the worst airline for customers of size is United Airlines, which only offers a 31-inch seat belt—and requires consumers to pre-reserve their seat belt extender requests.

- There’s a reason why seat belt buckles are so different in airplanes. As Atlas Obscura notes, lift-lever lap belts, a common design choice for seat belts in early cars, quickly were replaced with a press-button design in many vehicles, but airlines have generally kept the older design, which stays fairly secure but can be taken off easily, in case there’s an emergency or you have a hankering to see how small the bathrooms have gotten in modern airplanes. Plus, there’s less risk of accidental pressings. “A car-style push-button buckle, which is typically mounted at the hip, could open on impact if something bangs against the button,” the site’s Dan Nosowitz writes. “And given the meager room in economy class, nobody wants to be digging around between the seats to find a buckle in a crash situation.”

1930

The year that Dr. Claire L. Straith, a plastic surgeon based in the Detroit area, put a safety belt in his own vehicle, a part of his role as an auto-safety innovator. “The attitude toward the problem has greatly changed in recent years,” Straith told the Detroit Free Press in 1957, adding that vehicles were increasingly designed with safety in mind. Straith, who died in 1958, was one of a handful of doctors who put public focus on the auto-safety problem, even going so far as to patent new designs for dashboards to better absorb shock. His efforts drew the attention of Chrysler, which started selling vehicles with his safety recommendations starting in the late 1930s, though seat belts—along with the interest of the rest of the industry—would only come later.

Nils Bohlin, wearing his most important invention.

The guy who invented an important seat belt design, but gave away his patent

As a society, we often have strong opinions about the value of ownership, especially if we’ve invented something unique or novel—as highlighted in an epic New York Times story, from 2018, all about the unusual ownership situation around a specific type of bikini.

But what happens when you invent something so novel, so fundamental that you’re better off just giving away the patent for the invention for free, because it would do the public significant harm to keep a tight leash on ownership?

That was the situation Swedish inventor Nils Bohlin, an engineer for Volvo, faced when he came up with the three-point seat belt. If you’ve sat in the front seat of a vehicle sometime in the last 60 years, you’ve most assuredly seen this basic design, which not only secures your waist, but also your chest with a stretching belt mechanism that pulls out just as much slack as the passenger needs.

The two-point seat belt, which went across your lap and is still found in the back seat of many modern vehicles today, was an important innovation, but it was imperfect—especially in seats that are independently adjustable, generally in the front seat of vehicles or the middle seat of minivans—and were known to cause internal injuries during car crashes.

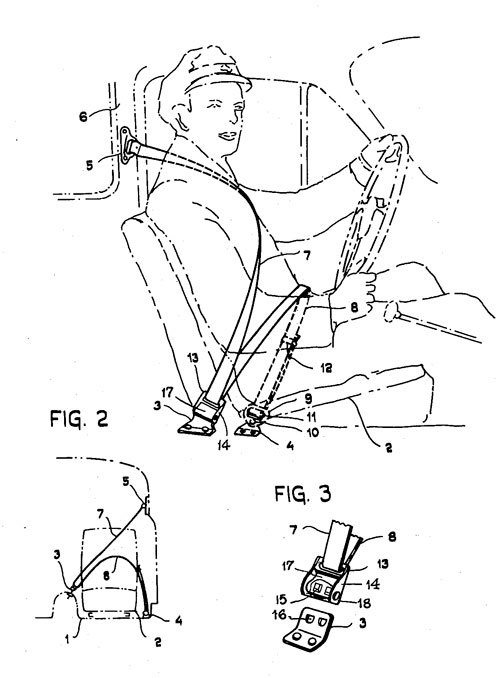

This guy is strapped in and ready to go. (Google Patents)

Bohlin’s patent filing for the three-point seat belt, originally field in the U.S. in 1958 and granted in 1962, warns that even cars that have separate belts for hips and chests are susceptible to forces so dramatic during crashes that “the load-resisting and retaining properties of the belt are impaired to such an extent that the strapped person is not safely prevented from being thrown against the wind-shield or steering column.” Bohlin’s three-point seat belt, an attempt to simplify a more complicated four-point approach used in military settings, provided an important alternative, one that treated the belt as a single mechanism. As the filing explained:

The object of the present invention is to provide a safety belt which independently of the strength of the seat and its connection with the vehicle in an effective and physiologically favorable manner retains the upper as well as the lower part of the body of the strapped person against the action of substantially forwardly directed forces and which is easy to fasten and unfasten and even in other respects satisfies rigorous requirements.

This seat belt design could have provided an important competitive advantage for Volvo, which was one of the few car companies at the time to have a chief safety engineer on staff—a situation that, according to History.com, came about as a result of a relative of Volvo’s then-CEO, Gunnar Engelau, dying in a car crash. Bohlin, who previously worked on safety mechanisms for fighter jets at the Swedish aerospace giant Saab, brought much of that thinking to Volvo’s cars.

“It was just a matter of finding a solution that was simple, effective and could be put on conveniently with one hand,” Bohlin said of his design, according to a 2002 Times obituary.

But it soon became clear that the patent would be more useful as an official standard that was mandated at a regulatory level by state and federal governments. For years, the automobile industry’s own handling of seat belts left a lot to be desired. Seat belts, 1949-1956, a 1979 report created at the behest of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, highlighted the fact that making car safety a matter of consumer choice led to wildly different results among manufacturers.

In 1955, Ford tried to emphasize safety options in its vehicles, including the offering of seat belts, which was a novel option for vehicles at the time. The marketing campaign was spearheaded by Robert McNamara, a Ford executive who just a few years later saw his profile increase significantly as the U.S. Defense Secretary. But while Ford’s efforts at safety were legitimate and drove interest in the vehicles, the company was competing against General Motors, which made no effort to emphasize safety in its own vehicles at the time—instead focusing on more traditional concerns among car manufacturers, such as speed. In a marketing war, speed won out.

Losing a sales battle, Ford soon backed off of the safety language in its marketing—though the report suggests this turned out to be a huge mistake:

Declining sales were the reason given by Ford executives for scrapping the safety campaign. The implicit rationale was that campaign was that safety hurt sales. But it is not at all clear that the safety responsible for Ford’s sagging sales. Instead of hurting sales, the safety campaign, according to some Ford Division officials, had helped in a bad sales year to sell about two hundred thousand more cars than expected. It had been an important fact, some Ford executives felt, in preventing a disastrous sales year.

Ford’s decision, the report argued, proved hugely damaging for the automobile safety movement, leading to years of lost momentum—momentum that was only picked up after federal regulations were put into place.

Volvo’s work, however, did not go unnoticed. A turning point for the three-point seat belt came in 1967, thanks to Bohlin, who published a report based on years of crash statistics involving Volvo’s three-point seat belt, and found that the belt prevented fatal injuries among passengers in vehicles involved in crashes below 60 miles per hour. The impact of the report encouraged the National Highway Safety Bureau, a just-formed predecessor agency to the modern National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, to push for the belt to not only be an important add-on for vehicles, but for the device to come standard in all vehicles—a key victory for the automobile safety movement, and one that put safety beyond the whims of marketing.

Thanks to the astute timing of Bohlin and Volvo, the three-point seat belt became a part of the regulations enacted with the American National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966—soon replicated throughout the world—and became the way the public buckled itself in.

Volvo realized that what it had was more important than royalties, and gave away its patented design to other manufacturers, free of charge, to build and improve upon. This move, over the past 60 years, has likely saved hundreds of millions of lives.

Reflecting on the decision in a 2009 retrospective article, an Australian Volvo executive put the move as such: “The decision to release the three-point seat belt patent was visionary and in line with Volvo’s guiding principle of safety. It’s why we like to say there’s a little bit of Volvo in every car.”

In a world where patents are often used as expensive weapons, Volvo’s decision is refreshing.

But, more importantly than that, it’s life-saving.

The seat belt is an important innovation that highlights the value of creating consistent standards for the common good. Sure, there have been plenty of different seat belt designs over the years—you’d be hard-pressed to find a button-press mechanism along the lines of the ones used on Chrome Industries bags in a modern-day vehicle—but for the most part, the ideas that drove Nils Bohlin survive to this day.

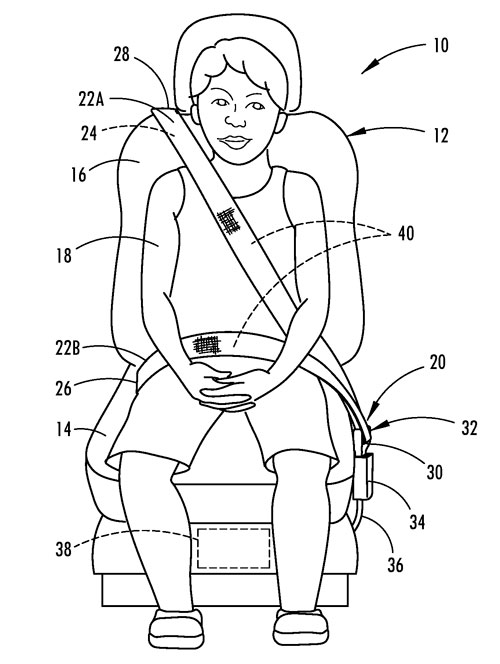

Of course, there’s always room for innovation. A few years ago, Ford raised some eyebrows in the world of automotive news when a seat belt patent of theirs surfaced. The patent, for a heated seat belt, extends a more recent trend among vehicle makers to add temperature control to seating from the person’s backside to the person’s front side.

This edgy teen is happy because their seat belt is heated. (Google Patents)

The patent is lengthy, discussing the process of adding a heating mechanism to the webbing of a seat belt strap. But some were skeptical, such as CarBuzz’s John Tallodi, who noted the obvious technical problems of such a solution.

“Now there may be some merit in this system, but being wrapped up in electricity should you be involved in an accident just doesn’t seem like a very good idea,” he wrote. “They also don’t mention what would happen if the seat belt frayed over time or if you were to accidentally spill some liquid on it while strapped in.”

Something tells me that if they pull this off, though, they won’t be sharing this patent with their competitors.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

And thanks again to Nightfall for sponsoring over the last month. We were happy to have them.

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium122518.gif)

/uploads/tedium122518.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)