Camper Van Mainframe

Why the first “portable” computers, produced before integrated circuits, would really stretch the term today. Some portables needed a truck to move.

Find your next favorite newsletter with The Sample

Each morning, The Sample sends you one article from a random blog or newsletter that matches up with your interests. When you get one you like, you can subscribe to the writer with one click. Sign up over this way.

Today’s Tedium is sponsored by The Sample. (See yourself here?)

“I was working at the Bureau in a mathematical group that was eager to recruit him, because we needed someone with his computing skills. My supervisor asked me to help with the paperwork and ‘get Leiner.’ I did help with the paperwork and Alan joined our group. A year later we married, and after we married I said to my supervisor: ‘You told me to get Leiner, so I got Leiner.’”

— Henrietta Lenier, an employee of the National Bureau of Standards in the 1940s and 1950s, discussing how she met her husband Alan. The couple, speaking to the Computer History Museum in a 2004 oral history, noted that they were not allowed to work directly together due to a nepotism rule at the bureau, which led Henrietta to voluntarily leave the bureau’s computer team and work with its electron tube laboratory instead. (Despite being pushed into another team, Henrietta still worked closely with NBS’ computer team.) Alan would become a key figure in the creation of the DYSEAC, one of the first “portable” computers ever produced.

The DYSEAC computer, which was really freaking large.

Before computers had transistors, portable computers looked like the DYSEAC

Looking at a picture of the DYSEAC, it’s bizarre to think that anything so huge and unwieldy would be considered “mobile” or “portable,” but in the context of 1950s computing—before a time when most people even had the chance to sit in the vicinity of a computer, let alone use one—it sort of made sense.

The machine, produced by the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) at the behest of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, is widely believed to be one of the first computers designed to be transported around. But the machine, based on the earlier SEAC computer produced by NBS in 1950, may have been the least-portable “portable” device ever created.

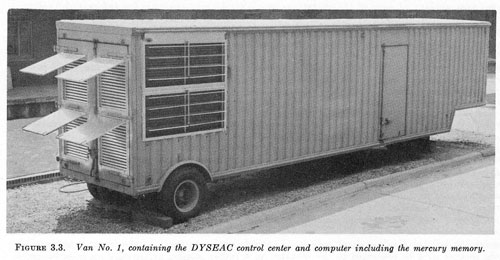

Per a 1961 survey of the computer industry by the Ballistic Research Laboratories, the computer weighed 20 tons and required two separate trailers to function:

There are two trailer vans. Van No. 1 contains the control console, input-output, computer, storage, and 12 tons of refrigeration capacity. Its internal dimensions are approximately 39 x 7 x 9 feet and weighs about 12 tons. Van No. 2 contains DC power supplies, 6 tons of refrigeration capacity, and 1,700 cubic feet of spare space. This van also has internal dimensions of 39 x 7 x 9 feet. It weighs 8 tons.

Perhaps part of the reason why the computer was so big was that its creator were trying to top SEAC, which drew a bit of buzz upon its release. SEAC, paid for by the U.S. Air Force, was called a “Giant Brain” by journalists who covered its creation, noting the speed of its computing capabilities.

“It multiplies or divides eleven-digit numbers in 250 one-millionths of a second and is described by its inventors as the fastest computer in operation,” a 1950 New York Times article breathlessly explained.

While Alan Leiner, who designed SEAC, would later note to the Computer History Museum that NBS employees didn’t like such terminology, it was nonetheless a machine that was impressive for its time.

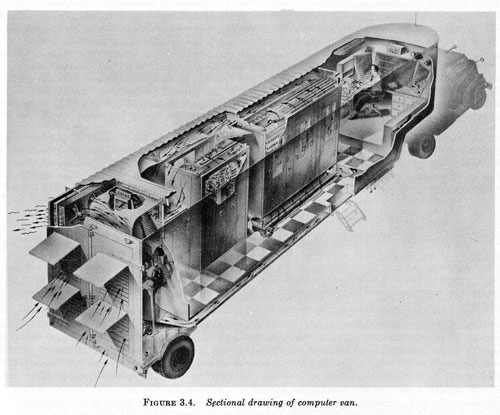

An artist’s rendition of the inside of a DYSEAC.

That said, it was incredibly limited by modern standards. For one thing, it could only hold 512 words in its storage, initially relied on a relatively small number of vacuum tubes, could only initially handle 11 types of instructions, and had a memory cabinet that was five feet wide and seven feet high. (The computer itself, while small for its day, was much larger.) It was not a machine that could be easily taken on the road. But it was nonetheless a huge leap forward in computing, and was used for, among other things, the first photo-scanning device used with a computer.

DYSEAC, conceived around the time SEAC was in its completion stages, used the prior machine as a jumping-off point. A 1951 document on DYSEAC’s design, written by Alan Leiner, explained in detail the expected similarities and differences between the devices. DYSEAC, which would come online around 1954, would share some design decisions with the older machine but it would have a wider array of functions.

“Of the 16 types of operations performed by the DYSEAC, five types are the same as those in the SEAC, five types represent variations or expansions of their SEAC counterparts, and six are either entirely new or completely revised,” Leiner wrote, citing one example.

In the oral history he and his wife did with the Computer History Museum, Leiner noted that the design approach was driven by the reliability of the components used in SEAC, a machine that, despite having numerous moving parts, rarely broke down.

“For this Signal Corps machine, our engineering group took the original components of the SEAC and designed a new hardware package, which my staff and I utilized in our logical design of DYSEAC. This new hardware package sufficed for implementing virtually 100 percent of the internal logic of DYSEAC,” he explained. “Each small piece of the logic was called a ‘stage’, and the logical structure of the entire computer was completely described by specifying the one-to-one wiring connections between the stages.

It required extremely close control of the identity of each one of thousands of stages, as well as each pair of connections.”

The approach taken by the NBS team led to a number of innovations that have made their way into modern computers. For one thing, it’s widely believed that the device represented one of the first uses of printed circuit boards in a computer.

The machine also, beyond its portability, was capable of interacting with other computers in real time, a very primitive form of what today would be considered cluster computing or even grid computing. In 1956, NBS teamed with the U.S. Navy to test the ability for SEAC and DYSEAC to combine their computing resources and work together on an issue.

This was made possible thanks to a feature in the DYSEAC that allowed it to manage the information from another machine, making it the nucleus of sorts. In a 1956 article in Computers and Automation titled “Two Electronic Computers Share a Single Problem,” the fact that the computers shared differing capability levels, a fundamental feature of modern cloud computing, was played up.

“Only one of the two machines, DYSEAC, had the flexible system design features that provide for multiple program processing and interruptibility necessary in the interdependent system,” the article stated. “However. this limited experiment did demonstrate the significant fact that two machines need not have identical capabilities and characteristics in order to share a common data-processing program, provided that one machine has the necessary

flexibility.”

To put this all another way, while DYSEAC was a computer that was meant to go places, it was also an innovative machine in its own right—and not just because it fit the bare-minimum definition of “portable.”

1956

The year that the Army Signal Corps put out a call for a general purpose mobile computer that would effectively be a replacement for the DYSEAC. Eventually, the company Sylvania won the contract and produced the MOBIDOC, which was fully transistorized and as a result only required one trailer, rather than two. The project became very popular with the Army and the machines were heavily used in Army installations during the early 1960s. (Of note, Jean Sammet, the first female president of the Association for Computing Machinery, was the head of software development for the MOBIDIC project for Sylvania.)

That giant box on the right is the “portable” computer.

RECOMP: When “portable” meant that you could lift a computer with a buddy

Currently I have a mini-fridge next to my desk. While it started life as a wine fridge, I use it for beer, mostly. It is not a very quiet fridge, and sometimes I have to close it with some force to get it to quiet down. If Tedium ever becomes a podcast, which I still get asked about doing about twice a month, I will have to get rid of this fridge, or at least unplug it.

I would not consider this wine fridge to be very portable. I could potentially lift it myself, but I might struggle a little bit. I probably would want to empty it out of its contents before I tried it, though.

This mini-fridge is roughly the same size, dimensionally, as the RECOMP II, a computer produced by Autonetics, a division of North American Aviation, in 1958. But it weighs a whole lot less. The computer, about 4.7 cubic feet in size, is about two feet tall and weighs 197 pounds.

(via Computer History Museum)

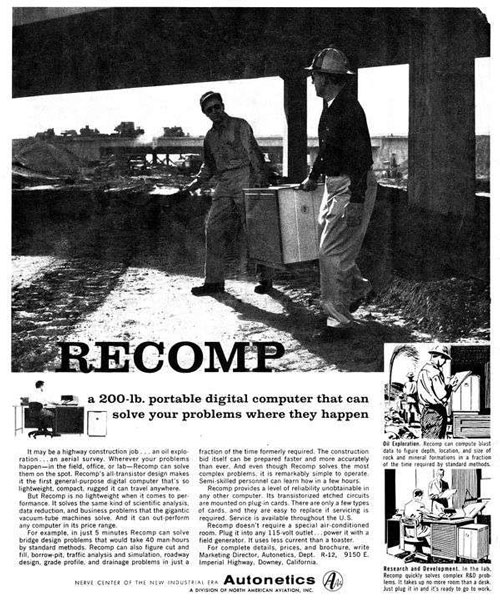

A major selling point of the device, as pointed out by this ad that describes the machine as “a 200-lb. portable digital computer that can solve your problems where they happen,” is that it could be lifted by two people, meaning it could not only be used in an office environment, but it could be brought into a work site.

(It was predated, by a year, by a machine called the RECOMP I CP-266, which was intended for the military.)

The device, despite being significantly smaller than the DYSEAC and coming out just three years after DYSEAC was given to the U.S. Army, was arguably more functional—in no small part because it was one of the first transistorized computers sold for commercial use. While the DYSEAC was faster at performing functions like addition and multiplication, the RECOMP II could store more data—4,096 words, compared to 512 words. It also had an array of accessories, and, unlike the DYSEAC, actually had a chance of fitting in your office.

“The five components of RECOMP II—compute and memory, photoelectric tape reader, typewriter, tape punch, and console—work together to produce problem solutions previously reserved for only the most expensive system,” a brochure for the device stated.

Of course, all that power wasn’t cheap. The RECOMP II sold for $95,000 at the time of its release, which meant that those who used it often rented the device. And those rentals weren’t cheap either. At $3,000 per month in 1961 money, you weren’t renting one of these by accident.

We’re fortunate that portable computers actually started being smaller than a breadbox at some point, because I can’t imagine what lifting one of these into a Starbucks would do to my back.

1973

The year that IBM created a prototype called the SCAMP, or Special Computer, APL Machine Portable. The machine is the first portable computer as you might recognize them today and led to the creation of the IBM 5100. The 5100, while also sold as portable, wasn’t the weight of an iPad, either: It was a solid 50 pounds. It did, however, come to influence the IBM PC.

When it comes to portable computing in the modern day, we know what happened next: Processors got better, technology kept improving, and eventually people became addicted to their phones.

It’s a dog-bites-man story, one that you already know by heart.

So I’d like to finish off by highlighting a fascinating coda to the rise of the early “portable” computer. It’s to be found in the careers of Alan and Henrietta Lenier, who took their work designing the earliest computers in a bold new direction, one that looked intently at the human brain.

Starting in the 1960s, Henrietta Leiner moved on from her career in computing, going to grad school to spend time researching the way that the human brain processes information. She was inspired to do so due to her work in computers.

“I knew that computers could do some of their cognitive work much faster than could the human brain, but I also knew that computers were less versatile than the human brain in processing information,” she said in her oral history.

Eventually, Alan followed her into this interest and left the computer industry himself. And by the 1990s, by the time both were in their 80s, The New York Times spent much time hailing the work that the couple had done to research the role of the cerebellum, the lump on the bottom of the brain, in shaping the brain’s evolution. Henrietta’s research in particular, apologies for the pun, changed a lot of minds and is now widely considered a turning point in our understanding of the brain.

“People had the intuitive feeling that you had to go high up in the brain to get higher functions,” she said in the 1994 article. “But I know from computers that the location of computing elements is not critical in a hierarchy.”

Maybe it took a giant computer, one that is very much bigger than a breadbox, to eventually get to this point. But consider the point underlined.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

And thanks to The Sample for giving us a push this time. Be sure to subscribe to get an AI-driven newsletter in your inbox.

:format(jpeg)/2018/03/tedium031518-1.gif)

/2018/03/tedium031518-1.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)