Math + The Mechanics

The story of the Curta Calculator, a stylish portable mechanical calculator that doesn’t use electricity and has a surprisingly dramatic origin story.

Tonight’s GIF features YouTube user Jaap Scherphuis showing off a Curta Calculator.

Sponsored By 1440

News Without Motives. 1440 is the daily newsletter helping 2M+ Americans stay informed—it’s news without motives, edited to be unbiased as humanly possible. The team at 1440 scours over 100+ sources so you don't have to. Culture, science, sports, politics, business, and everything in between—in a five-minute read each morning, 100% free. Subscribe here.

1820

The year the arithmometer was first patented in France. The device, invented by Charles Xavier Thomas de Colmar, was the first successful mechanical calculator. A full-desk size well-suited for an office environment, It helped set the stage for more than a century of mechanical calculator production starting in the 1850s. The elaborate devices weren’t very portable, but proved very influential to a device that was.

Hand-cranked calculations: The story of the Curta Calculator

The handheld electronic calculator innovated in a lot of ways—it was electronic, it had an ever-changing screen, and it was likely the first device most people owned that had a board of silicon baked inside.

But one first it did not own was portability. Portable calculators were already relatively common at the time that the first electronic ones appeared. They just didn’t rely on electricity.

You can thank a guy named Curt Herzstark for that.

During the 1930s, the Austria-born Herzstark realized there was demand for a number-crunching machine that could fit inside a pocket. It made sense, really, but the adding machines that existed at the time, made by American companies like Burroughs (whose corporate history I covered here), weren’t designed in a way where they could easily shrink.

Herzstark, as a salesman for a company that sold adding machines—his father, Samuel, improved on the design of the Thomas Arithmometer by making it electrically powered—was very familiar with the weaknesses of these large machines from a miniaturization standpoint.

In a 1987 oral history he took part in with the Charles Babbage Institute of the University of Minnesota, he explained that he saw the solution to the problem was that the machine needed to be built in a way that considered the mechanics of the human hand:

You can imagine, that one could readily miniaturize a machine just like a watch maker. But what can you do about entering and reading the number? You would have to work it with a pin. A small machine must also be the right proportions for the hand. So, it was clear that the whole world longed for a small machine. That was a fact, and there wasn’t one. And I became involved in this naturally.

His solution? A cylinder that was full of little adjustable dials, as well as a hand crank. Set the dials up a certain way and it could add, subtract, even multiply and divide. It took a little bit to understand how everything worked, but once you got the hang of it, it was a pretty effective way to do some quick math problems on the fly.

Perhaps the Curta Calculator wasn’t instant the way it is on a solar calculator, but it’s pretty close.

Mat Taylor, the guy behind the always-fun YouTube channel Techmoan, did a quick clip on the device in 2014, highlighting its ability to do math, its cultural interest, and its surprising value in the modern era. (Just check eBay.) The video highlights how a little twist changes the addition from single numbers to numbers in the hundreds.

“This is one of the few things I’ve featured that has retained its value after all these years,” he stated.

Admittedly, Herzstark wasn’t the the first to come upon the cylinder as the ideal shape for a handheld mechanical calculator. As the website History of Computers notes, there are multiple examples of inventors who found potential in the round shape, including 19th-century Norwegian inventor Axel Jacob Petersson, who showed off examples of his machines at multiple global exhibitions but doesn’t appear to have mass-manufactured them. And around the turn of the 20th century, an inventor named Christian Hamann came up with a device that had a hand crank somewhat similar to what Herzstark made.

So, if it wasn’t first, why talk about the Curta calculator at all? Two reasons: One, it’s one of the sleekest machines ever created, the kind of thing worth nerding out about; and two, the story of what Herzstark had to go through to actually get the device to market is very much a tale of its time—and one worth discussing.

“Americans are the world leaders in mass production. But every now and then new products come out of Europe that serve to remind us that Swiss watchmakers and other Old World precision artisans are still without peer in their fields.”

— A 1952 New York Times brief discussing the sale of the Curta Calculator by a Lichtenstein-based company called Contina, Inc. The device’s precision reflected the nature of the manufacturing world of its time, and was a truly innovative device that reflected a kind of craft and precision that was not traditionally associated with products used for math. With a going price of $134.70 ($1,514.80 today, adding in that pesky inflation), it was priced similarly to a watch, as well.

Curt Herzstark, shown in Vienna in 1942. (Computer History Museum)

The Curta calculator, an important invention, was nearly lost to history

I haven’t exactly spilled the beans of what happened to Herzstark’s invention as of yet, but you might have figured it out simply based on some of the surface details I’ve already mentioned above: He was working on the invention in the 1930s, he was based in Austria, and the device wasn’t actually released for sale until the 1950s, by a company that was based in another country entirely.

That’s right: The Curta Calculator was almost never made, due to the events of World War II. But by a combination of sheer luck and savvy on Herzstark’s part, he survived, allowing this invention to come to life.

Before Germany’s 1938 annexation of Austria, Herzstark was at a turning point in his life. His father had just died at the end of 1937, with the family just at the point of figuring out how it should split up his inheritance. Herzstark was supposed to get the factory, which would have been convenient, given his aspirations.

Meanwhile, his work on what became the Curta was nearing fruition—he had all of the basic concepts of the device figured out and had put in place patent filings; he simply needed to build them.

But the German takeover of Austria changed all that. Herzstark’s sheer existence was challenged by Nazi rule, as under the Nuremberg Laws, he was considered a “mischling,” or mixed-blood person, of the first degree, because his mother was Catholic and his father Jewish. This could have been devastating for his family, just like it was for many other families.

But the existence of the factory, and its sophistication, provided cover for Herzstark, as German officials decided to let the factory continue operating, developing items like measuring instruments and distance gauges that were used in the wartime effort, though they weren’t allowed to create the calculating devices they were previously known for.

“I knew how in principle to build a machine for the hand in 1938. Naturally the moment that Hitler came all of this was put aside,” Herzstark explained in his oral history. “First, we were not allowed to build any more calculating machines. Secondly, I said to myself, this is a living for me perhaps if I emigrate or something. Aside from that, we were fully occupied building measuring instruments.”

His mother owned the factory; he was simply an employee. And with that distinction in place, for the next few years, the factory was allowed to operate without issue until 1943, when two employees of the factory were caught listening to the BBC and transcribing what was said using a typewriter. The man who owned the typewriter was beheaded; the other man was sentenced to life imprisonment. Herzstark attempted to stand up for his employees, but this soon led to scrutiny of him.

He was soon charged with a number of crimes himself, including “helping Jews and subversive elements” and “indecent contact with Aryan women,” and taken to the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany. He said the charges were completely fabricated.

“Later, I determined from a dozen other technical people in Buchenwald that they were arrested like this or under similar circumstances,” he stated.

His track record before being taken to Buchenwald, however, might have protected him from a worse fate and likely saved his life. He was given a role in a nearby factory and told that, if he followed orders, he would have a decent life in the camp. The head of the factory, meanwhile, was familiar with his work in Austria, and he was given special access to the factory to make sure everything was running correctly.

His reputation, and that of his factory in Austria, also made it possible for him to save other prisoners, by bringing them into the factory to work, notes historian Nick Booth of the University College London.

The interest in his prior work also gave Herzstark something else: A motivation to keep working on the Curta. As he explained in the oral history:

The Gustloffwerk people made the following proposition to me. We will allow you, even encourage you, to continue working on your invention. However, you can do so only on your own free time. On Sunday, you can make drawings of this construction. When that is finished we will make a model. And when the whole thing is finished and if it is well done, so that it really functions, then we will give it to the Fuhrer as a present after we win the war. He will certainly make you an Aryan so that you can live in peace and as a German.

How honest that was, I am not sure. But for me, at that time, it was naturally a “saving anchor.” I said to myself, as long as I draw and work on this machine, I will be allowed to live in the camp. So I worked on the CURTA invention on Sunday morning in the factory and in the evenings often for more than an hour after lights-out, when the others were already sleeping. I worked in the workroom and also where we ate with the permission of the production scheduling officials of the Gustleffwerk. And so the CURTA machine was drawn up in pencil but completely with dimensions and tolerances. The drawings were finished, luckily, exactly when the war was over.

This device, which he had spent many years building in his family’s Vienna factory, was rebuilt once again, from memory, in drawing form, with the idea that it would be potentially be an elaborate gift for Hitler.

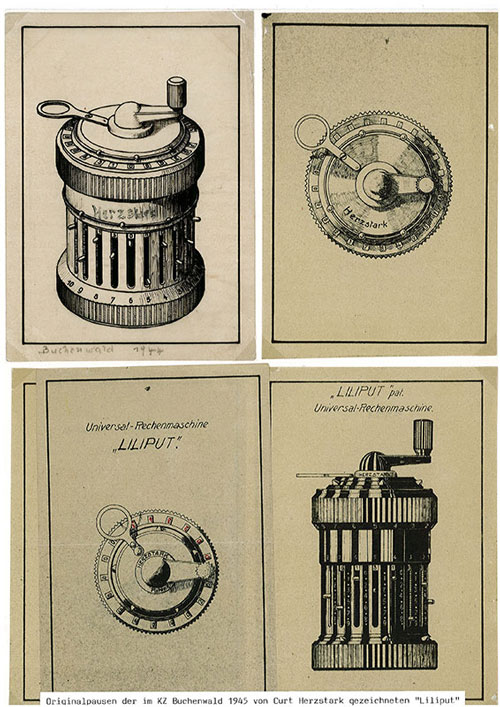

Some of the drawings of the Curta Calculator Herzstark produced while in Buchenwald. (Yad Vashem Museum)

This was not just a machine. It was the thing that kept Curt Herzstark alive.

“It was incomprehensible. If I’d been a lawyer or something, I would have died miserably,” he later recalled of his unusual situation, according to a quote in a 2004 Scientific American article. “They would have sent me to a quarry, and in two days I would have died like this. God and my profession helped me.”

(The quote wasn’t current at the time, it should be said; Herzstark died in 1988.)

Of course, Hitler never was presented this machine. The war ended, and he was free to pursue the Curta once again outside of captivity, and after a false start in East Germany, the product eventually drew the interest of the Prince of Liechtenstein, who invested in the product and supported its production.

It was a surprisingly fraught road for a fairly ingenious invention.

141K

The estimated number of Curta units produced, according to a factory production list acquired by the website VCALC.net, which has heavily documented these devices. (Herzstark, who was critical of the company that ended up producing them, said that if they had been marketed properly, they could have sold in the millions. He had put the production estimate in his oral history around 150,000 to 160,000, so there could always be more.) Online fans of the mechanical calculators have gone to the step of aggressively tracking the serial numbers on the bottoms of the devices, which seems like the perfect kind of hobby to have around a calculator.

Even without its wild origin story and high functionality despite an utter lack of electric power, the Curta Calculator would be an insanely impressive device—it’s a well-built object with literally hundreds of parts, the kind of thing that if you’re into it, you’re really, really into it.

There are lots of examples of people being really into it. Websites for this device speak to a level of interest that rivals, say, mechanical keyboards, except with an even narrower niche. (The high cost of buying one probably is a big reason for that.)

Perhaps the most prominent recent example of this kind of obsession comes from former Mythbuster Adam Savage, who featured a 3D-printed Curta Calculator replica on his YouTube channel Tested. The device’s many parts were considered so complicated that the designer of the replica, Marcus Wu, had to build it at 3X the size, just to make it possible to 3D-print and install everything.

“I’m having trouble not using expletives, I’m so excited,” Savage stated during the clip after unboxing the giant replica, before letting a few out with the help of some aggressive bleeping.

The Curta Calculator is the kind of device that elicits responses like that. As it should. Curt Herzstark went through a lot to make it a reality.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal!

And thanks again to 1440 for sponsoring. If you’re looking for a little more unbiased news in your inbox, a signup to the 1440 list is just the place to start.

:format(jpeg)/2018/08/tedium082318.gif)

/2018/08/tedium082318.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)