On “Ernie”

Having learned that Baidu is about to steal my first name for its AI chatbot that’s launching this month, let’s talk about the name Ernie for a bit. (Can I stop them?)

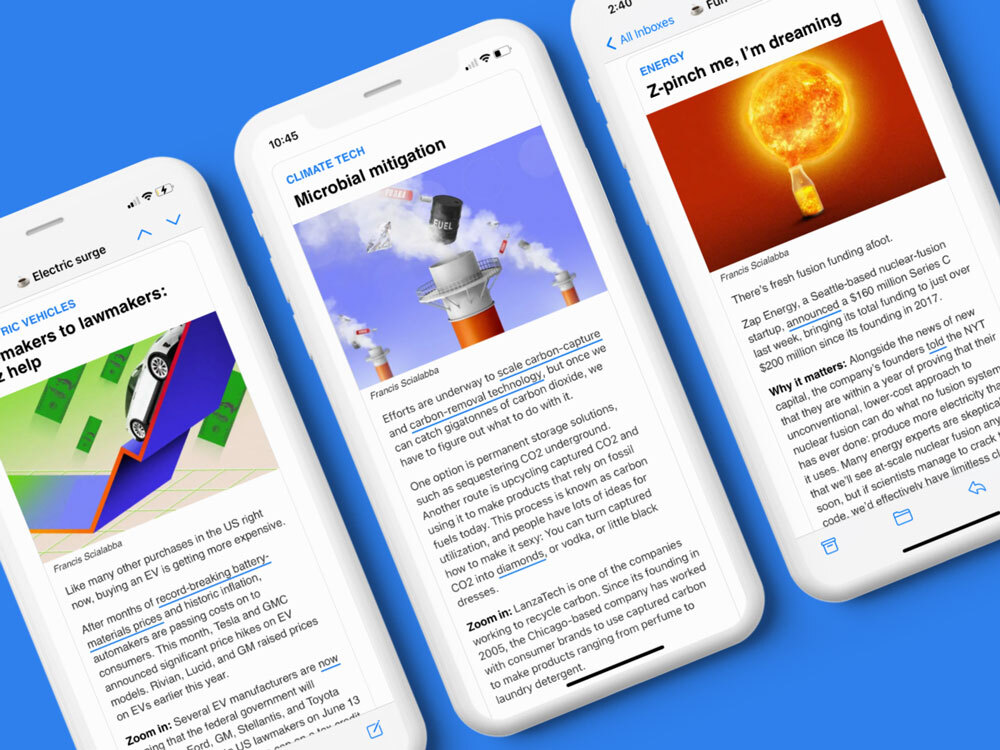

Sponsored By Tech Brew

Tech news is confusing—so we changed that.

Join over 450K people reading Tech Brew—the 3-times-a-week free newsletter covering all updates from the intersection of technology and business. We provide free tech knowledge that’ll help you make more informed decisions.

[button]Subscribe For Free[/button]

1945

The year that Ernie was at its most popular among baby names, according to the Social Security Administration’s baby name resource page. (Ernest, the “full” name that is often shortened to Ernie, was much more popular, especially in the first half of the 20th century.) The name fell off in popularity around the late 1980s, and even Ernest has seen a sharp decline in recent years. Per The Bump, Ernie is no longer among the 5,000 most popular names, Ernest is no longer in the top 2,000, and after Ernest saw a sharp decline in the last decade, Ernesto is now more popular than Ernest. (However, other sources disagree: Baby Center, which now integrates its own user data, claims the name is making a big comeback, and Ernie is now in the top 1,000 once again.) As for the peak of its success, I’m going to credit the popularity of Ernie Pyle for helping to bring the name to the start of the Baby Boom.

Why yes, I’ve heard the song “Rubber Duckie” before. Why do you ask?

Why “Ernie” is the perfect example of a hypocorism

Ernie didn’t start as Ernie. As noted by Wikitionary and other places, the roots of Ernie started as something closer to ernustuz, a term with Germanic roots, which reflects a certain sense of seriousness or strength. (Pretty sure Sesame Street and Ernest Goes to Camp tag-teamed to totally ruin that nomenclature, but I digress!)

To put it another way, Ernest has evolved over time from a lengthy German name to a name that that escapes borders and is commonly shortened in an oddly piercing way.

Despite the oddity of this name—I don’t know about you, but I don’t run into many Ernies throughout my day to day—I should point out that there are a lot of people there named Ernie, and a lot of them specifically named Ernie Smith.

I am not the most famous Ernie Smith. Glenroy “Ernie” Smith, a Jamaican reggae musician, is. Here’s his most famous song. Enjoy.

The Wikipedia disambiguation page for Ernie Smith lists seven separate Ernie Smiths, none of which are me, while the related disambiguation page for Ernest Smith has 13 entries. I know of at least three separate successful musicians named Ernie or Ernest Smith, numerous athletes, and at least two generations of Ernies that came before me. (As far as I know, I’m the only Ernie Smith that is a modern-day journalist, though I haven’t looked closely.)

Now you might be wondering: Why do people shorten this name from Ernie to Ernest? (Or, in Sheryl Crow parlance, why is it that when his name is William, is she sure it’s Bill or Billy or Mac or Buddy?) That’s because of the concept of the hypocorism, a Greek-derived term that essentially means “pet name.” Yes, we not think of it as such, but Ernie is a pet name, a sign of affection in nomenclature. By not calling me Ernest, you’re showing a sign of appreciation towards me.

These phrases have a tendency to evolve over time, much as the English language itself has. The linguist Peter Trudgill has noted that strongly formal names like Ernest likely evolved into their less formal forms, like Richard to Dick, or Edward to Ed to Eddie, to help support poetic rhyming schemes.

As Trudgill wrote for The New European back in 2020:

But there is another interesting development which can occur in the case of names like Edward: Edwards very often get called, not Ed but Ted—or even Ned.

Nicknames like Ted have been in use ever since the Middle Ages; and it is intriguing to think about how these particular hypocoristics came into being.

They clearly resulted from a playful process which involved speakers in taking an abbreviated one-syllable hypocoristic name and replacing it with some rhyming syllable. Other hypocoristics of this type included Bob from Robert via Rob, Bill from William via Will, and Nell from Helen.

Other well-established nicknames which were arrived at as a result of the same sort of ludic process include Dick from Richard, and Peg from Margaret, though in these two cases other complications came into play.

By that logic, it’s easy to see how we got Ernie. Ernest does not lend itself to an easy rhyme, but a name like Ernie, which ends on a long “e” sound, ends as many other words do.

(Another effect of this, which is not the case for Ernie, is that the push to make names work better in poetry would lead to names with fewer syllables, like Michael to Mike.)

This gradually led to less formal name structures, which have over time become more common. Hence, Ernie.

ERNIE

The name for the artificial intelligence engine, developed by researchers at Baidu, which the company aims to bring to its customers sometime in the coming weeks. The engine, whose name stands for “Enhanced Representation through kNowledge IntEgration” and has been in development since 2019, appears to have been a real stretch for them to reach, given that it’s not even a proper acronym.

/uploads/Chatbot.jpg)

Why must we humanize the names of our chatbots?

I mean, if a chatbot is coming to steal my name, I wouldn’t be the first. I’m sure the legendary triathlete Siri Lindley cursed a little the day she found out that there was going to be a chat assistant on everyone’s phone named Siri.

I’m sure everyone named Alexa must hate that when someone calls their name at home, a bot is competing for the actual person’s attention. And I bet you if Sydney Pollack was still alive, he would be pissed that Microsoft decided to give its search engine’s chat engine the nickname Sydney.

I mean, even I’m a little guilty of this. In 2009, when I started ShortFormBlog, I decided it would be a clever idea to create a mascot for this site, which I named Julius after my middle name, which I’ve never been a fan of, as a way to take ownership of this thing I never really liked. But I never thought about how other Juliuses would feel about it. Maybe I should have called up Julius Erving for his thoughts.

In all seriousness, though, I do sort of wonder why large technology companies do this. The closest I got came from a Fortune interview that David Limp, the senior vice president of devices and services at Amazon, did about seven years ago:

We did go through a number of names and the name is important as much for the personality that it creates around the persona than is this computer-based voice computer in the cloud. But there’s computer science behind it, too…[I]f any of you have Echoes, you know that it only wakes up when it hears the word Alexa, and the phonics of that word and how that word is parsed and the fact that it has a hard consonant with the X in it, is important in making sure that it wakes up only when it’s asked for. And so, a combination of those two things allowed us to kind of narrow in on Alexa.

(It also helped that they already owned the Alexa name, having purchased it many years ago from Brewster Kahle and Bruce Gilliat, the founders of an early search engine-turned-archival service. Kahle used the money from that purchase to fund the growth of the Internet Archive.)

It makes sense why companies would want to do this for purely practical reasons. After all, by giving something a name, the odds are that you are less likely to trigger it by accident decline sharply. After all, think about how easy it is to trigger Google, a much more widely used phrase, in comparison to Alexa, a term that (unless you have someone in your life with that name) you will probably not say quite as often. Google is, famously, a verb, so it’s much easier to say in common parlance.

In the case of Baidu, Ernie is not a particularly common name in the market which it serves. (If this page is to be believed, you can call me 厄尼.) If it was in America, even, they would find a lot of people like me who hold onto their Ernie identities but for the most part, it is not overwhelmingly common in culture.

So Baidu is going to have users chatting with Ernie; it’s going to have people asking for Ernie’s help in their cars. Soon, Baidu is going to make Ernie a household name for literally hundreds of millions of people in one of the world’s largest markets.

In many ways, as much as it will frustrate me personally, it is likely the right way for them to go.

“It is not only about language, but also about understanding Chinese culture. Ernie 3.0 is already a very localized AI foundation model for the China market, which means the generative large language model we are working on right now will be more suitable in China.”

— Baidu CEO Robin Li, explaining why the Ernie Bot makes sense for the Chinese market where other models, like ChatGPT, do not. “We have been working on LLM for a few years. We launched Ernie in March 2019, and have scaled it up with well over 100 billion parameters,” he added.

Once, when I was in the eighth grade, I was asked by a fellow student what I would name whatever future child I might have. I said I wasn’t sure.

The person who asked then replied with something along the lines of, “You’re not going to name him Ernie, are you? You wouldn’t want to do that to the poor kid.”

Yes, Ernie is not a great name in a schoolyard setting, where literally any excuse that people can find to bully someone else is turned into fodder for more bullying. One of the most famous puppets, one that literally every child sees at a young age, shares my name!

But on balance, I just want to say that Ernie is a great name. It’s short. It’s memorable. Its syllables are evocative, and it has four of the most popular letters in the alphabet. It sounds unusual, but it’s extremely common. It has fallen out of popular flavor. If current numbers hold, there are literally going to be less Ernies when I die than when I was born.

I’m now in my 40s, sans child. I may or may not ever have a kid. I’ve gone back and forth on this idea of giving someone my name. To emphasize, I don’t think giving someone generational baggage is the way to go. But I also think, hey, it didn’t turn out so bad, this weird five-letter name that Baidu now wants for their conversational AI engine.

Ernie is a great name, especially when you’re old enough to appreciate it. It’s the kind of name that people remember, it’s one that baristas and fast-casual workers will commonly misspell, and I wish more people saw just how great it was.

But I would prefer that the way they see it is not through the search engine that they use every day. Even if that search engine is half a world away.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal! And thanks to Tech Brew for sponsoring.

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium031123.gif)

/uploads/tedium031123.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)