The Loophole

On the history and psychology of free samples—from free bars of soap to free AOL—and why you can no longer get drunk in Gatlinburg for free.

Sponsored By TLDR

Want a byte-sized version of Hacker News? Try TLDR’s free daily newsletter.

TLDR covers the most interesting tech, science, and coding news in just 5 minutes.

No sports, politics, or weather.

“Something is either free or it isn’t. You can’t arrest somebody for thievery if it is free.”

— Minnesota woman Frankie Lingitz, whose husband Erwin Lingitz was at the center of a legal dispute in 2013 after he was arrested, jailed, and roughed up after he reportedly took 1.5 pounds of food samples from a Cub Foods location in White Bear Township. (The suit was eventually dropped, meaning that we didn’t get deserved legal precedent from the situation.)

/uploads/babbitt_soap.jpg)

When did we figure out free samples were a thing?

Let’s be clear, samples are everywhere. They are a key part of marketing philosophy. Whether it takes the form of a trial, a book of paint colors that help you decide on how to fashion your home, a small smidgen of nourishment from a sample at a grocery store, or something that gets delivered or mailed to you, we have been getting free samples for a long time.

The idea of sampling is that it’s supposed to get you addicted to the product so that you keep buying the product, possibly so that you keep buying forever.

In the book Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America, author Wendy A. Woloson, a historian at Rutgers University–Camden, suggests that one of the very first products offered with the veneer of free was the Presbyterian magazine The Christian Advocate, which encouraged its readers to convince other people to subscribe to the publication in exchange for their own free subscription. (Less a free sample, in my view, more a very early example of affiliate marketing.)

But the soap industry really kicked off the trend, with Benjamin T. Babbitt helping to drive attention towards soap as a marketable product. Babbit, who got his start pitching his products from a traveling wagon, eventually landed on the idea of selling soap in bar form, which he was then able to offer to easily offer to curious customers. He wasn’t alone in the soap market, according to Woloson, noting that similar soap-sellers and proto-LinkedIn personalities like Hibbard P. Ross were quick to follow suit.

Ross was particularly aggressive as a salesperson, offering deals that were designed to entice additional purchases. One such example, listed on an 1850 flyer that reads like a long-form Instagram advertisement, encourages people to buy commodity soap from him for the right to get a discount on fancier, more expensive items. In other words, he was a grifter, but he seemed quite talented at it!

In many ways, free samples are the original sin of modern marketing, the word-of-mouth yin to mass market advertising’s yang. It is a way to develop a relationship with a good, whether a piece of information or a product that one really likes.

And if you really get into it, you can find free samples online all over the place. The above video, from the YouTube channel Under the Median, is a great sample of what it’s like out there for discount-hunters these days. (Something telling about the need to embrace samples to live within your means, side note.) Essentially, to get free stuff, you have to often share personal information, do a bit of digging, and wait a while to get the products sent your way. If you want to exploit free samples, it is definitely possible, though I recommend you pace yourself, lest you become the next Erwin Lingitz, a man whose Google results are now tainted because he’s the guy who sampled too aggressively.

Some brands make samples a huge part of their overall appeal. Costco is an excellent example. The membership-based store, also known for its low-cost concessions, has built something of a cult audience around creating samples that bring people into the store even if they’re not even looking to buy something. We’re so used to this kind of thing that we treat the people who give us free stuff like garbage. That was a point underlined in a story from earlier this year on Reddit, in which a Costco sample distributor noted how samplers seemed kind of disrespectful and unwilling to play by the store’s rules. A noted passage:

Don't get mad at me for doing my job. I have to stand there all day and can't sit down on anything or I'll get written up. I have to get a doctor's slip to be able to use a stool, and even then I'd only be allowed to sit down for 15 minutes per hour. And don't try to start a fight because I told you something. Some guy tried to fight me because I told his adult daughter not to reach over and grab stuff.

I think this points to the challenge of free samples: It’s an excellent way to try something, but it‘s so easy to exploit by the recipients of the free thing, with only social norms keeping things in check.

Which brings me back to my moonshine story.

/uploads/0409_aoldisks.jpg)

Five successful examples of free samples that kicked brands into the stratosphere

- In 1894, Coca-Cola launched both free samples and coupons by offering free tastes of its soda to people across the country by handing out free tickets. The tactic worked.

- In 1915, Wrigley mailed 1.5 million samples of its gum across the U.S., helping to get people interested in chewing it all the time.

- The beauty brand Estée Lauder won over cosmetics fans through a clever strategy that mixed commerce and samples in the 1950s—if you paid a certain amount, you got a free bag of samples to go along with your product as a gift. Why’d it work so well? As the B2B website PYMNTS put it: “Consumers are more likely to spend more than they initially intended in order to qualify for the free gift. In light of this, brands and retailers can strategically define minimum purchase requirements that incentivize customers to increase their expenditures to get the gift.”

- An obvious example of free samples from the 1990s came in the form of AOL, which distributed around 1 billion CDs with customers over a 13-year period, a physically wasteful approach that nonetheless made AOL one of the biggest brands in the world.

- A darker example of a free-sample success story comes in the form of pharmaceuticals, particularly the controversial opioid Oxycontin, which found success with doctors in the form of both free samples for patients, paired with free gifts of “minimal value” for doctors, in the form of paper and pens. As one letter-writer to the New England Journal of Medicine put it in 2018: “Opioids are potent stimulators of the reward system of the brain, so getting a free “taste” of these medications can precipitate compulsive and long-lasting seeking of substances that reproduce their effects—a phenomenon typically exploited by drug dealers.”

97%

The percentage of customers that try free samples mailed directly to customers, according to research from the e-commerce firm Brandshare. The company’s research found that between 14% and 33% of customers convert to the brand, a level that suggests that it’s worth the trouble to send free samples to consumers.

/uploads/15918397352_16dda8255f_c.jpg)

Why the free moonshine samples in Gatlinburg are no longer free

So back to my story about the moonshine.

For those not familiar, the rise of hard alcohol samples is actually a relatively recent phenomenon in the mountain towns of eastern Tennessee. For decades, it was difficult to legally produce distilled spirits in the state, which led production to go underground.

Tennessee was famed for its liquor. After all, Jack Daniel’s promotes its Lynchburg, Tennessee production prominently on its packaging. But the hard part, for years, was building a new distillery.

In 2009, that law changed, allowing for distilleries to be created based on a very specific framework of ownership that required a bunch of ducks to be in a row.

"It's not a distillery bill; it's a jobs bill. The fact that they distill spirits is really irrelevant in my mind," said Tennessee State Rep. Joe Carr, who sponsored the bill, in 2009 comments to Knoxville Biz.

/uploads/6202363559_46a1a21572_c.jpg)

It wasn’t designed specifically to allow moonshineries to be legally launched, but that was its ultimate effect.

Gatlinburg, both known for its proximity to a massive national park and its tourist trappings, was the most obvious beneficiary of the law, with Ole Smoky Distillery among the first out of the gate, launching in the summer of 2010. Sugarlands Distilling Company, its most prominent competitor, launched in 2014. Both tend to rely on clever flavored adaptations of the moonshine concept, and have gotten increasingly experimental over time. If you’re in the market for alcoholic pickles or peanut butter-flavored moonshine, they have already thought of both of those things.

To be clear, this is not a hipster mecca. These are mainstream businesses, as highlighted by the fact that Ole Smoky’s current spokesperson is retired NFL superstar Jason Kelce.

The decision to offer free samples is a natural for these kinds of businesses, because of how they function. Simply put, you walk in as a tourist, try a bunch of flavors, and once you land on a couple you like, you spend as much as $25 on a jar of this stuff. Presumably, people walk in, try $5 worth of samples, and leave with $100 worth of alcohol. Last time we were there, they gave you free carrying cases to lug around your mason jars of flavored liquor.

So, why did they start charging money for these free samples? Easy—they got local pressure to do so. In 2016, the major distilleries in the city voluntarily started charging $5 for tastings, which the city described as a “step in the right direction to maintain Gatlinburg as a family-friendly vacation destination.”

Put another way, the free tastings were starting to change the city’s vibe into a spot where revelers who weren’t scared off by the city’s occasional bear sightings were walking around the strip and getting drunk for free. Plus, more distilleries were opening, creating a dynamic where you could literally walk from one distillery to the next and get completely sloshed without paying a dime. That meant that public intoxication was suddenly a problem.

In 2013, we likely benefited from the fact that the concept was so new that the market hadn’t played out long enough to determine that shops handing out mini-shots of moonshine might be dangerous. But eventually, the free samples started to look less like a loss leader and more like a social problem.

Sometimes, I wonder if free samples primed the pump for the modern digital economy, an environment full of carrots and sticks. For example, did a failure to properly contextualize samples lead to some long-term problems in how we approach information?

When it comes to online news, the decision to not charge for digital content has been seen as the original sin, and I think a big reason for that comes down to a decision to not put much sizzle on the steak. When everything is available for free, we treat the people who give it to us poorly, or at least without an appreciation for the work that goes into it.

This is where my internet experience started—with the promise of free.

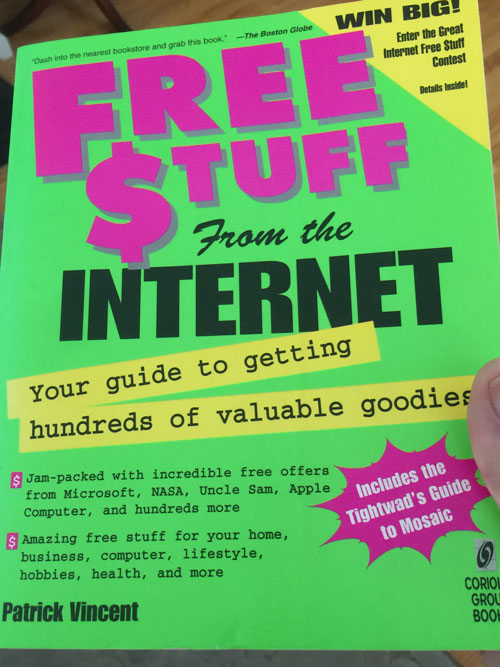

In a sense, this is to be expected. One of my very first experiences with the internet was a book titled Free $tuff From the Internet, which played into the idea that the benefit of the internet was that it was a way to access stuff with no limitations. Those limitations set expectations, and when the limits were ultimately re-programmed in, it put us into a situation where it was easy to exploit our desire for free things.

In a way, sampling free stuff is a two-way exploitation. The giver is exploiting your power of persuasion, and trying to convince you that you need to pay for their good or service forever. The recipient is trying to figure out just how far it can push the free end of the bargain, to see what they’ll let you get away with. I’m sure a lot of people spent time coming up with ways to stay on AOL by just using one free sample after another for years on end.

But the thing is, free samples are the onramp to enshittification. It is how companies, good or bad, get your attention. It is the psychological trick that gets you hooked, so eventually you buy expensive ham you don’t need and subscribe to a million cloud services you never actually use.

If the deal turns sour or somehow harms the golden goose—like how the free moonshine samples were harming Gatlinburg’s family-friendly reputation—it will inevitably get reined in.

At least when I was sampling moonshine for free, I got toasted.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal! And shout out to the people who know that free samples are an opportunity to bend the rules.

:format(jpeg)/uploads/tedium111024-1.gif)

/uploads/tedium111024-1.gif)

/uploads/ernie_crop.jpg)